Hamish McRae: Quality, not quantity, likely to be the way ahead as banks try to boost lending

Economic View: I personally find it astounding that the West could have allowed such a build up of debt to occur

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A move from quantitative easing to qualitative easing? Instead of just printing the money and hoping it sloshes to the right place, you guide expectations of short-term interest rates, find ways of boosting loan supply directly, clear blockages in the banking system and so on. That seems to be the way central banking will go over the next three years and the issue is whether this will be pumping by another means or a series of genuine innovations that will make monetary policy more effective: quality, not quantity.

We had two major new chunks of information yesterday. The less important, but more immediate, was the detail of the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee’s latest meeting, the more important the start of US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke’s two-day testimony to Congress.

The first showed that Mark Carney, the new Bank of England Governor, has brought unanimity to the MPC, for by promising guidance that rates would stay low for a long time, he reversed the minority calls to increase QE. Unanimity of itself is not necessarily a desirable feature, for a diversity of opinion can be a sign of open minds. But in this instance it is encouraging for it signals that the Bank will seek to find ways of maintaining a policy that supports growth, without stacking up the risks associated with QE as practised to date. Our central bank already holds more than one-third of the national debt. At some stage that debt will have to be sold back to real savers and the more you add to the pile the greater the stock overhanging the market. On the other hand, we do need to keep credit flowing, so let’s try to find cleverer ways of doing that.

The second set of information appears at first sight less innovative but suggests too that the Fed will seek to be sharper in its management of expectations. The line Mr Bernanke followed was twofold. First, we should separate QE from interest rates: thus the tapering down of the Fed’s monthly purchases of treasury stock should not signal a rise in rates. Second, policy will be tightened according to what happens to the economy, with faster growth leading to faster tightening and vice versa.

That is all common sense. What is pretty clear is that the Fed was shocked by the quite vicious reaction in the bond markets to its recent indications that the monthly debt purchases would eventually end. A bit of rowing back was now in order. So let’s assume that the Fed will tighten as and when it feels safe to do so, but it will try to signal its intentions more sensitively.

So what does all this mean?

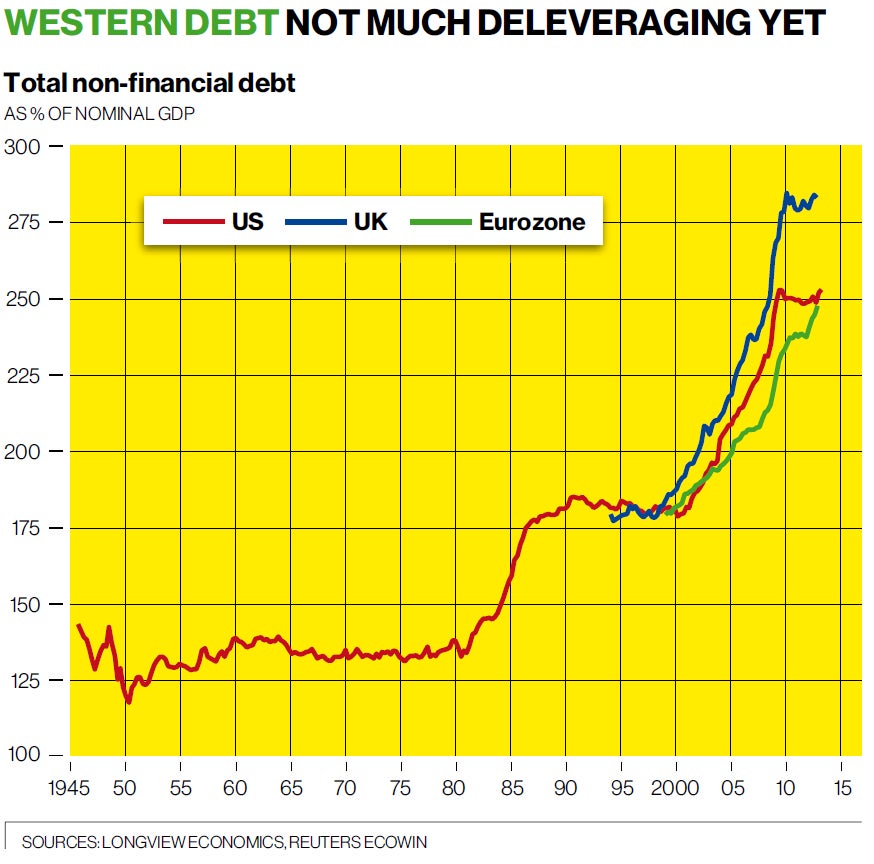

The developed world is carrying such a huge load of debt that changes in interest rates have a much larger impact than they would have done 20 years ago. You can catch some feeling for this from the chart, drawn from work by Longview Economics. It is kinda scary. These numbers are non-financial debt; so not all the stuff is in the banking system but real debt accumulated by real governments, real companies and real people.

As you can see there was a long, post-war period when US debt was around 125 per cent of GDP. Then through the 1980s it jumped to 175 per cent; and then, bang, from 2000 onwards it shot up to 250 per cent of GDP. I have added UK and eurozone figures for the later periods and give or take a bit, they are pretty much the same as the US. The UK is a bit high, because while companies and people are indeed cutting debt levels, the Government is still piling it up. But overall the similarities seem more notable than the differences.

So what do you do with all the debt? If we were Argentina we would write it all off, or at least most of it. Terribly sorry, chum, but we can’t repay and anyway you should not have lent us the money in the first place. That may well happen with Japanese and much of southern European sovereign debt, though the consequences would/will be dire. The more subtle way out is a combination of inflation and coercion: whittle away the real value of the debt and meanwhile compel savers to buy as much of it as you can by regulation and other means. I personally find it astounding that the West could have allowed such a build up of debt to occur – a 10-year period when policy went completely nuts – and I feel the governments, central bankers and regulators on whose watch it happened have not yet been sufficiently contrite about their failure.

Meanwhile, though, you have a world economy that has to deal with it. It is a world economy that cannot stand high interest rates, so it is not going to get high interest rates. But there is a really interesting further issue here, highlighted by Longview Economics, as to what you should do.

We need to get growth going. So should we maintain loose fiscal and monetary policies to stimulate “animal spirits” – Keynes’ expression – and stimulate growth that way? Or conversely, are animal spirits actually suppressed by high debt levels, in which case you have to find ways of cutting the debt, maybe by converting it into equity or where appropriate even by writing it off. There is, for example, no point in pretending that Greece can ever repay its debts. So better to acknowledge that than continue the fiction.

That leads to a final point. The West will have very low interest rates for a while yet. Savers must and will adapt to that. They will do so in part by taking on more risk, in part by buying equities, and in part by putting resources into real assets such as prime property. Indeed, that is what is happening now. So ultra-loose monetary policies are not cost-free and central bankers should, perhaps, be more aware of that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments