Hamish McRae: Out of bonds, into equities: if only it were that simple

Economic View: Companies have been very successful at protecting themselves during the downturn, but is this sustainable?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Something very big has, I think, happened in bond markets: the beginning of a long-term bear market. It actually began last summer, when the safe-haven bond markets hit their lowest yields for, well, ever. It was, you may recall, the height of the flight to safety, when interest on 10-year German Bunds fell to 1.2 per cent, US treasuries to 1.4 per cent and our own gilts to 1.5 per cent. As I have argued in previous columns, I don't think we will see those yields ever again in our lifetimes.

That, however, says nothing about the duration, speed or profile of the bear market, or about the different ways in which the various markets will perform. Typically these very long cycles last about 30 years – and the bull market began in the early 1980s when it became evident that the world's main monetary authorities would succeed eventually in controlling inflation. We can all make our guesses at the shape of the market, but they will be little more than that. What we can say is that a 2 per cent yield on gilts does not make much sense when the expectation for inflation over the next five to ten years is 3.3 per cent.

But if you do not want to invest in bonds, what do you do? In the past few days a number of fund managers, including Jim O'Neil at Goldman Sachs, have argued that global equities are set for, if not a boom, a solid recovery. My instinct is that this is right, but this is a much less obvious judgement, for there are substantial arguments against it. Buying shares back in spring 2009 does indeed look like a once-in-a-decade opportunity, as we argued here at that time. But now? That is more difficult.

There are two broad arguments in favour of investment in global equities. One is the "wall of money"; the other the "solid economic recovery".

The wall of money is the negative one. It goes like this. Central banks around the world have printed huge amounts of cash and seem likely to print more. It has to go somewhere, and global equities are, along with property and commodities, the most obvious place to go. Commodities have had quite a rough year, which has slightly diminished their shine. Property? Well, yes, but value is hard to find and the market is hugely complicated. You may feel that the US residential market has at last solidly turned, but getting in is quite tricky. Transaction costs are high, administration is tricky and the unwary investor is liable to be stuffed. So as a default as much as anything else, global equities push themselves forward.

The positive argument accepts all this but would back it with a bit of optimism about the world economy. The basic case here is that we are still in the early stages of what looks like an increasingly secure global recovery. There is plenty of spare capacity in most industries in most developed markets. You can have a debate as to whether that capacity is appropriate. For example: does the shift to online make a lot of retail capacity redundant? Will the European car market, now at its lowest sales for 30 years, ever recover? And do we need permanently smaller banks? But look at it the other way: there are few capacity constraints on expansion, so the developed world can grow for several years without hitting barriers.

Alongside this is the value argument. If you look at dividend or earnings yields compared with fixed-interest securities, equities are extraordinarily cheap. But that is not such a strong case if you believe that long-term interest rates are unsustainably low. There are a couple of further reasons for caution, particularly when you look at the US market.

One is that the share of GDP taken by company profits in the US is at historic highs. Companies have been very successful at protecting themselves during the downturn, cutting costs, shedding staff and boosting productivity. But whenever you see a number – in this case company profits – at an extreme level you should ask whether this is sustainable. Usually it isn't. So there may be a fragility in corporate profitability that is not being picked up.

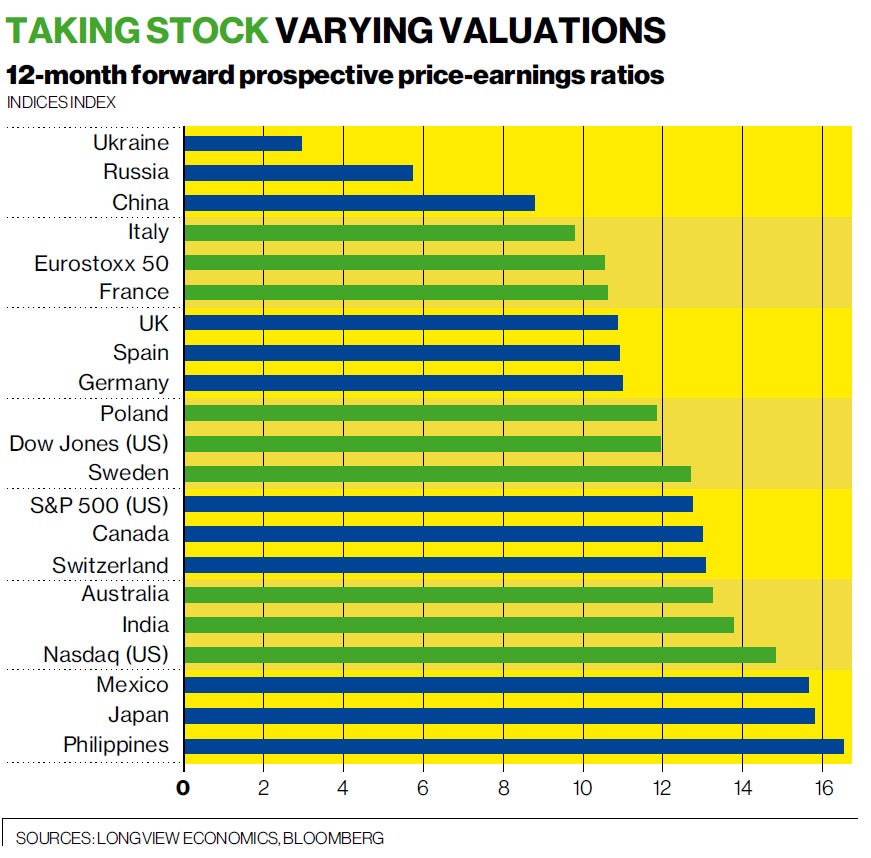

The other is that the long-trusted way of valuing companies, the price/earnings ratio, suggests that while most markets are not ridiculously expensive they are also not particularly cheap. At the bottom of equity cycles over the past century price/earnings ratios have typically dropped into single figures. Now they are in the low double figures. Of course it varies from market to market, and I have put in the graph some prospective ratios for a range of different countries. But the low teens are pretty much the average over the past half century.

That leads to the commonsense conclusion that shares are fairly priced rather than truly cheap. On this basis the US market is worse value than western European ones, and much worse than Ukraine and Russia – although other issues doubtless curb value there. The UK market – which reflects global prospects more than any other, for more than two-thirds of the earnings of the FTSE 100 companies come from outside the UK – looks better value than the US.

Those are the arguments, and the conclusion of Chris Watling at Longview Economics, who pulled together this data, is that assuming the US manages to sort out its fiscal situation and the eurozone gets through its current troubles (two big "ifs") global shares are indeed a good buy. But there is a solid view, articulated for example by Andrew Smithers of Smithers & Co, who believes that US shares in particular are significantly overpriced when compared with their long-term performance.

A lot of the difference comes down to whether the present level of corporate profitability is sustainable or whether profits are at a cyclical peak and will inevitably decline as a share of national income. I don't think we can know the answer to this. We have seen how banks became "too profitable" – that is, their profits were artificially and unsustainably inflated. But it is hard to see this as being true for global business as a whole, at least not on the same scale.

There is another concern: that the "switch out of bonds into equities" recommendation is now being made by so many people that, well, maybe it is just a bit too obvious. Sometimes the obvious however turns out right.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments