Hamish McRae: In Europe and the UK, it's a game of 'wait and see'

Economic View: As far as jobs are concerned, this is less serious than the 1980s or 1990s, and now is less serious than the 1970s

It is monthly decision day today for the Bank of England and the European Central Bank (ECB). While few expect any change in interest rates from either this month, people are now looking forward to November to ponder what the central banks might do next.

But something else has happened. The monetary policies of the central banks no longer seem to matter much.

Here in Britain, the Bank may or may not do another bout of quantitative easing in November, when the present scheme runs out. In Europe, the ECB may implement its bond-buying programme, buying the sovereign debt of the weaker countries, as recently announced. But in both cases the game is "wait and see".

We have to wait and see if the Bank of England's Funding for Lending scheme works: even if the funds are available, do companies and individuals really want to borrow? The latest data shows that mortgage-holders are repaying debt as fast as ever, which makes practical sense given the very low deposit rates. Why borrow at 4 per cent or more when your bank will only offer 1 per cent on a deposit? Far better to use any spare cash to pay off the mortgage.

In Europe, the ECB is also on hold, but for a different reason. It has staked out its intentions, and now has to wait and see what the weaker members do next. In practice, everything is on hold until Spain applies for a formal national bailout. Expect that later this month.

If monetary policy, both in Europe and here, has become pretty ineffective, and fiscal policy is being tightened everywhere, we are back to self-healing – the natural ability of economies, if left to themselves, to manage to grow. Can they do it, or has the great growth machine that has one way or another governed the world economy since the Industrial Revolution ground to a halt?

There are many strands to this debate, but it is a question which we will hear a lot more. It is not new. I remember in the strike-ridden late 1970s a celebrated political columnist pondering whether Britain was facing not just relative decline but absolute decline. That now seems absurdly pessimistic. Nevertheless, after four years of stagnant or falling living standards, it is a legitimate question.

The difficulty is separating the structural from the cyclical. We know we have experienced a serious cyclical downturn, but we don't know how much damage has been done to the nation's long-term productive capacity. Indeed, we don't even know how serious the cycle was, for the data is quite inconsistent.

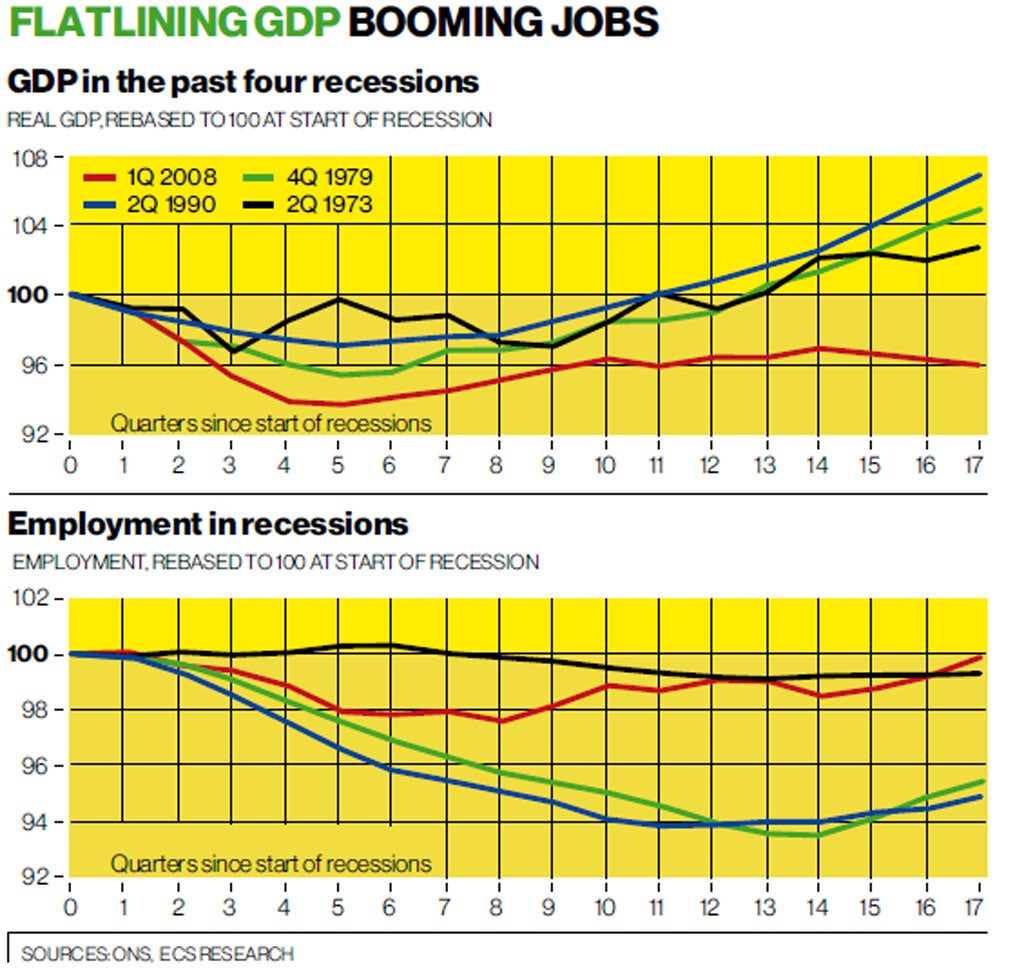

You can see that from the two graphs: On the top is what has been happening to published GDP this cycle compared with the recessions of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. As you can see, during this cycle, the red line is far worse than the other three. But below is what has been happening to employment.

As far as jobs are concerned, this has been much less serious than the 1980s or the 1990s, and now is less serious than the 1970s. The recovery in UK employment has also been much better than in the US or eurozone.

Some people have concluded that there has been a plunge in productivity, and that is what the figures would seem to show (productivity is calculated as a residual: you take output and you take employment and that gives you output per person). If so, it would certainly be bad news for long-term growth. But part of the explanation is almost certainly that GDP is being underestimated, as has been noted here before. Goldman Sachs reckons GDP is as much as 4 per cent higher than the official figures show, and ING Bank also believes GDP is seriously understated. Both have just put out papers on this.

The trouble is that even allowing for this understatement of GDP we still have a productivity problem.

If you accept that both output, like employment, is actually back to its previous peak, the harsh truth remains that there have been no gains in productivity in four years.

How might we explain that? There are three possible answers.

One is that the key problem is lack of demand. Once that picks up (and it looks as though real incomes will start to rise next year), companies will be able swiftly to increase output to meet that demand without having to take on more people to do so.

The second is that productive capacity has been damaged by the recession but this will recover as demand recovers.

The third is that productive capacity has been permanently damaged and much of the growth has been lost forever.

If the answer is some combination of the first two, then we can relax a bit. As demand recovers, supply will recover too. So we will be able to grow swiftly for several years without any labour constraints. Employment will rise but output will rise faster.

If, on the other hand, there has been permanent damage, then the longer-term outlook for productivity (and hence higher living standards) is bleak.

Goldman Sachs inclines toward the more optimistic assessment, and that would be consistent with the fact that many of the people now in part-time jobs say they would like to work full time. If part-timers work full time, their output (though not their output per hour) goes up.

There is, however, a long-term, structural concern. It is that while we will recover from this downturn in decent enough shape, it is proving harder to increase productivity in our predominantly service economies than it was in manufacturing-driven ones. Put crudely, you can increase productivity more easily in a factory than in an old folks' home.

This is a challenge for all so-called advanced economies, such as our own, and I don't see any easy way of responding to it.

Information technology has helped increase productivity in some service industries – think of the way we book a hotel or an airline seat online – but in some core services it is hard to see how this can be achieved.

So meanwhile, maybe our best hope is that the cyclical problem will resolve itself, and support a recovery in living standards, while we figure out how to crack the structural one.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies