Hamish McRae: Growing gulf divides the two Europes

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Yeah, but what about the European economy? The budget is essentially a political matter, not an economic one, so you can read the stuff over the past few days about that positively or negatively according to your point of view.

But while it is important symbolically, you have to remember it is equivalent to 1 per cent of Europe's GDP. That is simply not big enough to have a material impact on economic performance. For those who believe the future of the EU depends on whether the region is a successful or unsuccessful economy, what matters is whether EU membership on balance improves the competitiveness of its members, or on balance damages it.

That, surely, will be the question EU members will be asking themselves over the next two to three years as the recovery stumbles on and it becomes clear that there are several different European economies. Europe is a single trading area but one whose constituent parts are performing increasingly differently. That is an observable fact. And while it is impossible to be certain it does look very much as though this divergence will increase next year and beyond.

There are two fissures. One is between the northern and southern members of the eurozone. The other is between the eurozone as a whole and the non-members, including Norway and Switzerland.

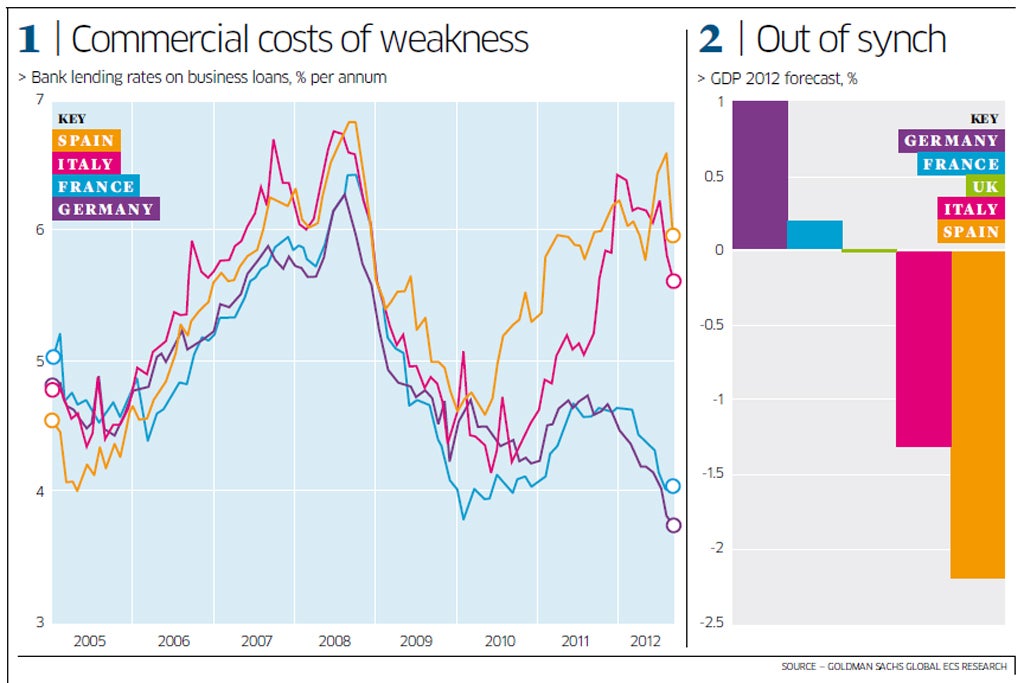

As far as the eurozone is concerned there is not a lot to be said that is new at this stage, except perhaps to note that the focus on the fiscal problems of the countries that have had to seek support has diverted attention from the problems of businesses in all the weaker countries. Thus, a company based in Spain has not only to cope with a collapse in demand in its home market but also higher funding costs. You can see that in the main graph, which shows the way in which the rate of interest on business loans of between one and five years has shot up in Italy and Spain but come down in France and Germany.

So the European Central Bank sets a single interest rate but borrowers in different countries have to pay quite different rates. As a result the weaker countries are not only being squeezed by tighter fiscal conditions; they are also being squeezed by tighter monetary conditions. You can see the projected economic outcome for growth this year in the right-hand graph, with Italy expected to shrink by nearly 1.5 per cent and Spain by more than 2 per cent, whereas Germany and France are recording a little growth. (These are Goldman Sachs' estimates, showing the UK economy flat.)

This phenomenon, that the eurozone is now no longer functioning as a single monetary area, has started to come up on the radar. The obvious question is whether that financing gap can be closed because the longer it persists the harder it will be for companies located in Spain and Italy to close the gap in economic performance.

But this, as you can see from the graph, is not new. What I think is new – or rather will be new when people cotton on to it – is the divergent performance between the eurozone and the rest of Europe that seems likely to occur next year.

It is quite plausible that the eurozone economy will shrink again next year, with growth in Germany and France more than offset by further declines in Italy and Spain. But there is a reasonable prospect of there being some growth in the whole of the rest of Europe. For example, Goldman Sachs has the UK and Sweden growing at 1.9 per cent, Switzerland at 1.2 per cent, Poland at 2.4 per cent and the Czech Republic at 1.7 per cent. The onshore economy of Norway is expected to grow by 2.7 per cent. Indeed Goldman thinks all the major non- eurozone European economies will grow by at least 1 per cent.

If the past three or four years has taught us anything it is we should be jolly circumspect about all forecasts. It is worth pointing out too that Goldman Sachs, along with others, has been too optimistic about the UK for the past couple of years. But you see the point. It does not take a great leap of imagination to see the eurozone holding Europe back rather than pushing it fddorward. It will not be holding Germany back because it will help keep German exports relatively competitive, but it won't be helping the rest of Europe.

Think about the consequences. If this divergence in performance lasts just a year or so, the EU can live with it. But if the eurozone, excluding Germany, stagnates for two or three years while the rest of Europe recovers, then it would face real danger. The various business advantages, such as transparent pricing across borders, would be seen to be more than offset by the damage caused by restrictive fiscal and monetary policies.

Up to now most of the debate about the eurozone has been about the costs of keeping Greece and other weaker members in, against the costs of a break-up. But let's assume the eurozone does stay together for another couple of years. If most members do much worse than non-members, the debate will change. It will not be about the costs of break-up. It will be about the best way of achieving growth: what bits of the European economy are growing fastest and how the laggards can catch up.

None of this is being discussed at the budget summit. There is talk of EU policies to promote growth but the EU budget is too small to make any impact either way. The danger is that the sheer unpleasantness of the whole argument, on top of the tensions in the eurozone and at the ECB, reduces the European business community's confidence still further. I suppose what is happening in the US Congress over the Federal budget is even worse, but it does rather reduce one's faith in the political process, doesn't it?

Human ingenuity will ensure the world keeps advancing

Something less depressing: positive prospects for long-term growth in the world economy.

There have been suggestions recently that the long-term growth outlook has deteriorated, and that, in the West at least, our children and grandchildren may have a lower standard of living than we do. The argument is that a combination of the debts incurred over the past five years in all developed countries, ageing populations, the shortage of raw materials and the squeeze on oil supplies will combine to hold down living standards in the so-called advanced economies.

While acknowledging these pressures, it seems to me that continued technological advance plus the scope for increasing productivity in service industries, should enable us to carry on improving living standards. We will all have to retire later but given increasing longevity that could be a benefit, not a cost.

Now I see Capital Economics has come to a similar conclusion. It argues that technology may advance more swiftly, not more slowly, and that the energy squeeze fears are overdone. While environmental concerns may chip away some growth, the costs of coping with these will be spread over many years. So not only will the emerging world be able to increase living standards by applying the technologies already developed, but the advanced world will carry on developing new ones.

My feeling is that, given human ingenuity, it would be odd were productivity to stop advancing. Indeed, as education improves around the world, the brainpower applied to problems will increase. Simple example: the way mobile telephony has been adapted in Africa to transfer money.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments