Hamish McRae: G8 leaders will be under pressure to get world economy flourishing

Economic view

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The original idea, back in 1975, was to have an economic summit between the leaders of the world's largest economies. Since then two things have happened. One is that what are now G8 summits have become progressively less about economics and more about politics. The 39th one continues that process. The other is that the economically important countries in 1975 are not the same as the ones now. Three of the Brics, Brazil, India and China, are not included, whereas Italy (and Canada, which joined in 1976) still come to them. The present members now cover only half the world's economic output.

But if the talks this week are principally political – and there is after all a war on – there are two areas of economic interest where co-ordination is needed. One is fiscal and has received a lot of attention: countries need to co-operate more effectively on tax policy. The other is monetary and has received very little: central banks have to co-operate on getting back to normal monetary conditions.

The second is, I think, more important, because getting the progress back to normality will be tricky. We have to end quantitative easing and to get back to real interest rates of 2 per cent plus on prime government debt, which would suggest nominal interest rates of 4 per cent or thereabouts. But the progress towards that will be fraught. We have caught a feel for how difficult it will be in the past month, when the merest hint of QE coming towards an end in the US provoked a sharp and potentially disruptive sell-off of bonds worldwide. It also brought to an abrupt end the stock market rally. But it has to be done because the costs of not doing so are greater than the costs of continuing the drug of ultra-cheap money.

There, however, is an interesting possibility that might make the weaning process easier. It is that because the recovery has been an unusually weak one, the expansion phase of the world economy might go on much longer than it did in previous cycles. So there will be more time to fix things.

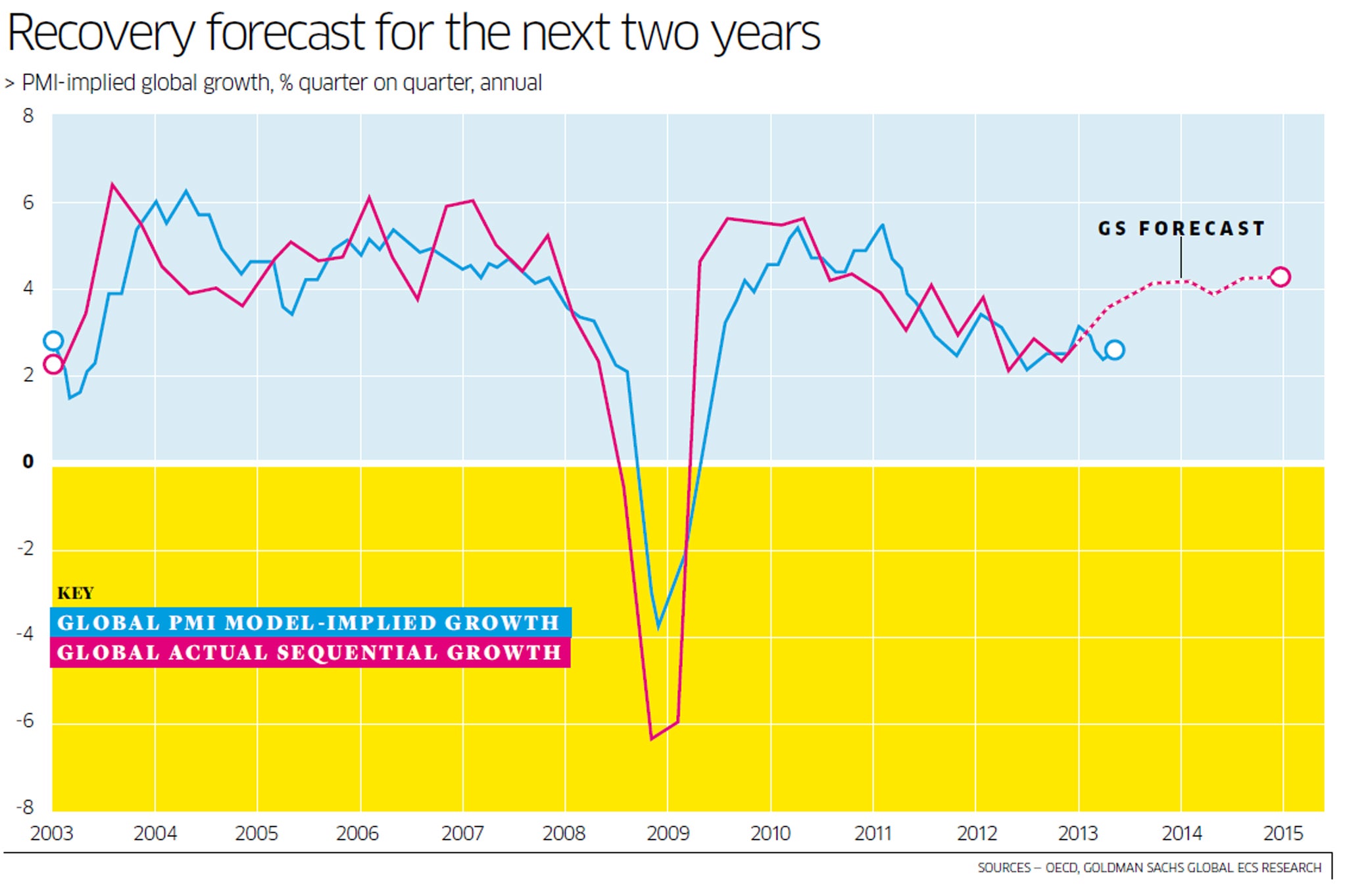

There has been a fair flow of positive news in recent weeks, which suggest that the next couple of years will see much better growth. Goldman Sachs has constructed a model for growth in the world economy based on the various purchasing manager indices and the forecast based on that is shown in the graph. If that is right (and we should treat with caution) there will be a couple of good years ahead. We are talking here of the world economy, not the UK one, but one domestic story would be consistent with that. The Federation of Small Businesses has just reported that the confidence of its members is at a three-year high.

Unfortunately, two better years, while most welcome, are not enough. The excesses of the last boom, the depth of the recession in the developed world, and the exceptional measures taken to re-ignite growth, are such that we need much longer to get back to some sort of normality. Again just to take the UK, we will in two years' time still be running a large deficit and hence still adding to the size of the national debt.

So why should we expect a protracted recovery? There are two broad sets of reasons.

The first are really mathematical and concern the amount of spare capacity in the developed world economy. It varies from country to country but as a general proposition output now is 10-15 per cent lower than it would have been had growth continued on its previous path. Some of that growth may be lost forever and in some countries we may be undercounting the activity that is taking place. But there clearly is quite a bit of spare capacity, not least in the labour market, and that will take years to absorb. You might say that we can go on growing for longer because we started further back.

The other set of reasons concern the quality of economic activity now, as opposed to the quantity of it. Consumption is no longer being puffed up by excess borrowing. On the demand side, in most countries, including the UK, household savings are back to their post-war normal levels. On the supply side, economies are getting back into better balance, with financial services shading back and other services taking up the slack. The public sector is becoming better balanced vis-à-vis the private sector. And the big international trade imbalances are to some extent, at least, narrowing to sustainable levels.

There is a further point here. Because it was such a serious recession, companies and governments alike have been forced to take difficult restructuring decisions, thereby increasing their productivity.

If this line of argument is right, then a co-ordinated plan for weaning the developed world off the drug of excessive monetary stimulus would bring huge benefits. Past experience says that the central banks are good at co-operating in extreme situations, when they flood liquidity into the system, but less good at cooperating during the long slog of tightening policy.

It is not the job of governments to tell central banks what to do, for they still retain a fair measure of independence. So this is not a direct summit issue. Nevertheless, if the G8 can manage to co-operate a bit more on fiscal policy, then that sets an example for monetary policy too. We do look like getting a longer-than-usual cyclical expansion – but the onus is on world governments and central banks of the G8 not to muck it up.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments