Hamish McRae: French need real choices in order to readjust

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.So now France has to decide. In the run-up to the elections the financial markets have been remarkably apolitical, you might even say mature, in their assessment of the promised economic programmes of the two principal candidates.

On the face of it you have one, Nicolas Sarkozy, who has achieved a reasonable degree of financial discipline, with the fiscal deficit for the past year coming in at 5.2 per cent of GDP, a little lower than the target of 5.7 per cent.

By contrast the main challenger, François Hollande, threatens war on the world of finance. There is a fine ring to that: “… and if markets are worried, I will tell them here and now that I will leave them with no space to act”.

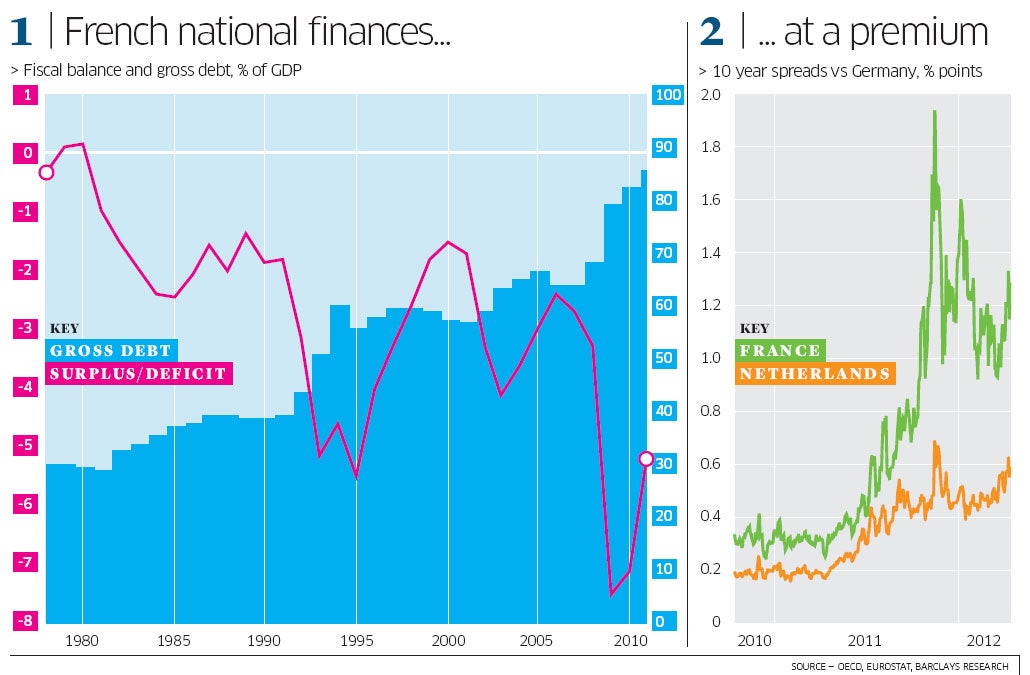

Both, in reality, are promising more austerity. Both say they will achieve a balanced budget, Sarkozy by 2016, Hollande by 2017, and if that were to happen it would be the first time since 1979. The long deterioration in French national finances is shown in the main graph – the UK, notwithstanding present troubles, was in surplus at the end of the 1990s. But now all governments in Europe, one way or another, are planning to get back to balance. So France in a sense is merely one more member of the austerity club.

The markets recognise that. The issue is not willingness to deliver sustainable finances; it is the ability to do so. Here France is in a middle band. It still has full access to the financial markets to cover its deficit but it has to pay a premium over the rate paid by prime borrowers such as Germany or the Netherlands. That premium has jumped about in recent months and, as you can see from the right-hand graph, is currently around 1.2 percentage points for 10-year money.

But the recent rise should not be attributed to fears of being “left with no space to act” following a Hollande victory in the second round. It is part of a more general bout of jitters concerning the stability of the entire eurozone.

So the most interesting issue raised by these elections is not whether the country is going to get more austerity. There is no real question about that. Rather it is how France will be nudged in the longer-term towards a more substantial redefinition of the relationship between the state and the people.

If you stand back and look over the past 30 years, France has in most respects been an economic success story. It has grown at pretty much the same pace as the rest of Europe. It has sustained high quality public services for the majority of its people. It has a clutch of competent and successful large companies. And it retains high-quality craft service and manufacturing industries. It also, in terms of output per hour worked, has the highest productivity in the world.

There are, however, two clouds, two aspects of the economy that have become increasingly evident as a result of the recession. One is unemployment, currently just under 10 per cent – the highest for 12 years. But France has had unemployment above 7 per cent since the early 1980s – except for a couple of brief periods it has been above 8 per cent since then.

This is a manifestation of the “insider/outsider” aspect of the French economy. And it is not just first and second-generation immigrants who find themselves excluded from the mainstream labour market; many well-educated young move abroad for jobs too.

The UK has been the principal beneficiaryof this trend. Estimates range from 250,000 to 400,000 for the number of French people living here, the majority having come for work. A similar number of Britons live in France but the majority of those are retired. More than 100,000 French live in Germany and some 90,000 live in Belgium, with roughly the same number living in Switzerland. Part of the drivers of this trend seem to be taxation, but the wider range of job opportunities available abroad are also a key lure.

The other cloud is the sustainability of the French model. You cannot Frenchneedreal choices in order to readjust go on piling up public debt as France has for the past 30 years. If you take debt as a whole, France actually has lower levels than the UK, for consumer and mortgage debt is higher here. So it is not debt as such that is the problem. It is the scale of the public sector debt and hence the role of the state.

An economic model that has 56 per cent of GDP spent by government, the highest of any large country anywhere in the world, requires very high levels of taxation. Even the French do not seem prepared to pay that amount of tax, as evidenced by the numbers that have chosen to work abroad. So something has to give, but when?

That seems to me to be the most interesting issue of all. As France ages, and as it resists increasing the state retirement age (Hollande promises to cut this back to 60), the public burden will continue to rise. You can always push things forward a year or so, as France has been doing for a generation. Relatively favourable demographic trends buy the country more time than, for example, Germany or Italy. (Italy’s population is forecast to drop from its present 57 million to 41 million by 2050.) But at best France will have a stable workforce, rather than an expanding one, paying for an ever-growing army of pensioners.

Someone, some political leader, will have to take the French people along this path of adjustment. If the debate is framed in terms of anonymous and greedy financiers pitted against the French way of life – the markets versus the people – then it is hard to see a happy outcome. If, however, the French were presented with the real choices of a low retirement age but poorer pensions, and lower taxation of working people and leaner public services, then they could make whatever choice they feel is right for them.

Ultimately, the people, not the markets, make these decisions. But the markets can and do bring matters to a head when savers become worried they won’t get their money back.

VAT and National Insurance paint the best picture of recession

The most awaited economic information this week will be the first quarter GDP figures, for were they to be negative there would be a flurry ofstories about Britain being back in recession.

Technically that would becorrect as the estimates for the final quarter of last year were negative. Actually, it is more likely that growth will have been seen to have resumed,particularly since there were some very strong retail salesfigures for March ... the result it seems of the good weather, if you can remember that.

But the big point is to takestatistics with a healthy dose of suspicion and the more these rely on estimates, the larger the dose. Thus last week's unemployment figures saw some downward revisions in thenumber of jobless.

There seems to be a general bias towards underreporting growth. The official figures were still showing the economy in decline when, actually, we were out of recession and the 2010 figures greatly underestimated growth that year. But we should not assume the numbers will always be too glum and I am a bit suspicious of those good retail sales.

If you want to know what is really happening, the numbers you should take most seriously are VAT and National Insurance receipts. VAT tells us how much money is being spent and National Insurance gives a good fix on what people are earning.

If both are OK we can relax; if they're not, we all need to worry.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments