Hamish McRae: Banking has a mountain to climb

Economic Life: The ability and the willingness of banks to lend is going to be constrained for some time

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is coming back – stability, that is – but it is coming back achingly slowly. Today's Financial Stability Report from the Bank of England charts the gradual return towards normality that has been taking place since the near-collapse of the global banking system last October. You can have a debate as to whether we have turned the economic corner yet but we have almost certainly turned the financial one.

Yet the report makes chilling reading. It is not so much the cool language with which it acknowledges how on a knife-edge things have been; I think we knew that. It is more the awareness of just how long it will take to re-establish a secure functioning world banking system. Confidence has come back to the financial markets and that is helpful; I find the notion of confidence more helpful than the expression "risk appetite" that market commentators often now use. But confidence has in a way run ahead of actuality.

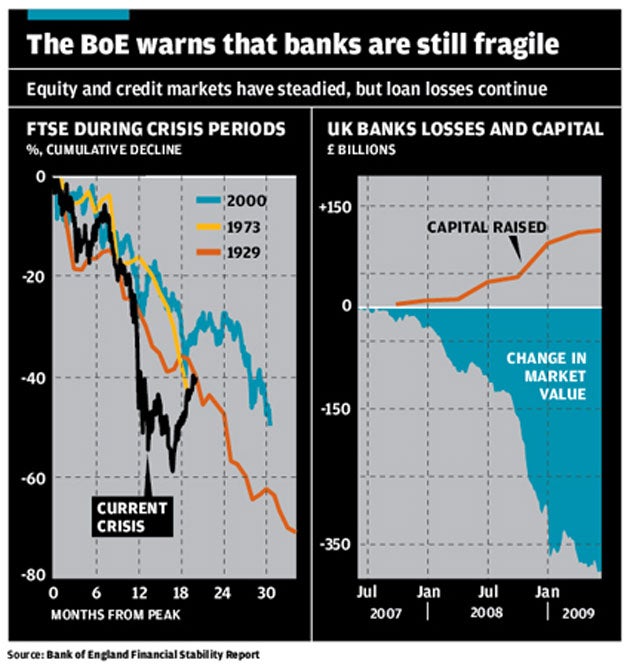

The simplest measure of confidence is global share prices. As the report points out, the main markets have recovered by between 25 per cent and 35 per cent from the lows in early March. But they currently look a bit soft and past experience would suggest that there is still a lot of uncertainty ahead. You can see the performance of the Footsie since this crisis began, compared with the main UK share indices after 1929, 1970 and 2000 in the top graph. Prices actually fell faster this time than they did in previous cycles. You can read that in two different ways. One would be to say that they adjusted more swiftly in discounting the damage and, accordingly, are now more securely based than they were at the same stage of the earlier cycles. The other would be to say they have run ahead of themselves and there are therefore likely to be serious disappointments ahead.

As so often, both responses have merit. The collapse of confidence did indeed bring prices to what may look like a once-in-a-generation buying opportunity. But there is a huge mountain to climb before growth is secure and, ultimately, the only thing supporting shares prices is the ability of companies to earn profits and pay dividends. They cannot do that until there is some overall growth.

This matters because a rise in share prices is crucial to paring back the losses of the banking system, pension funds and other investors, including individual ones. The Bank estimates that the rise in share prices since March has recouped about $8,000bn in mark-to-market losses (we used to call them paper losses – losses that existed on the books but not actually taken), while the improvement in credit markets has recouped a further $2,000bn. So, you could say that since early March the world has become $10,000bn richer, or at least that amount less poor.

You may say the world really isn't any richer, just as it really wasn't any poorer, as a result of these market gyrations. But sadly the losses are not just on paper and they do affect decisions in the real world. It is not just a matter for the banks. Companies all over the world have to cope with pension fund deficits, while Harvard, the richest university on the planet, has announced a series of redundancies following the fall in the value of its endowment.

The banks are, however, in the front line and you can see from the bottom graph that the decline in the value of major UK bank assets has far exceeded the value of the cumulative capital raised. So the banks are rebuilding their capital, but not as fast as the losses on their books.

One should not get too alarmed about this. At this point of the cycle, bad loans are bound to mount. The banks are making good profits on their continuing business and some of the potentially bad loans usually turn out better than they look at this stage. But the ability and willingness of banks to lend will be constrained for some time and, as the Bank of England points out, cross-border lending has been particularly weak. At times of crisis, the banks run for home.

So what happens next? The Bank points out that the unprecedented public support for the banking system is not a long-term solution, partly because of the fiscal pressure this puts on governments. So it makes a number of suggestions as to how a more robust banking system might develop. These include improved disclosure, greater market discipline, greater self-insurance including having a bigger buffer of capital for bad times, and better assessment and management of risks – all common sense stuff. The Bank's paper also acknowledges that there will still be bank failures and, therefore, deposit insurance, and that the authorities will need to retain their awareness of the possibility of systemic failure, the sort of cumulative breakdown that occurred last autumn.

But there seem to me to be three missing elements in this report. The first is the failure of the monetary authorities, particularly in the US but also in the UK, to lean harder against the property boom. Very low interest rates in the US helped to create the property bubble. I don't think any central banker in the world would deny that. So you could almost say you have to have a banking system that is robust against policy failure by the authorities. I don't expect the Bank of England to say that, but the rest of us can.

Secondly, there were other policy failures. We had a system of capital requirement that encouraged the banks to give back money to their shareholders and to economise on such capital as they did have by pushing things off-balance sheet – or so they thought. And thirdly, I suggest the Bank now seems to underplay the extent to which the markets have already changed bank behaviour. Investors require banks to be sound. When Royal Bank of Scotland comes to be sold back to the public, you can be certain that it will be rock-solid. We won't buy the shares if it isn't.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments