China's slowdown could actually be good news for the world economy

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At the risk of appearing perverse, let’s start with a counter-intuitive proposition. The slowdown in China, far from weakening the global recovery, might actually help it become more durable.

This is not, of course, what the markets think. They recovered a bit, but are still way off their summer peaks. The uncertainties there are echoed by the central banks. The principal reason why the Fed held off increasing US rates last week was the slowdown in China. Andy Haldane, chief economist at the Bank of England, suggested that an emerging-market crisis might become the third leg of the financial disruption that began in 2008-09.

Mario Draghi, the president of European Central Bank, acknowledged these concerns, although he concluded: “More time is needed to determine in particular whether the loss of growth momentum in emerging markets is of a temporary or permanent nature.”

Emerging markets have been weak for some time, but developed markets hit record highs this summer. There may well be more bad news to come, but a year from now it is perfectly possible that the latters’ earlier positive judgement will turn out to be more valid than their present negative one.

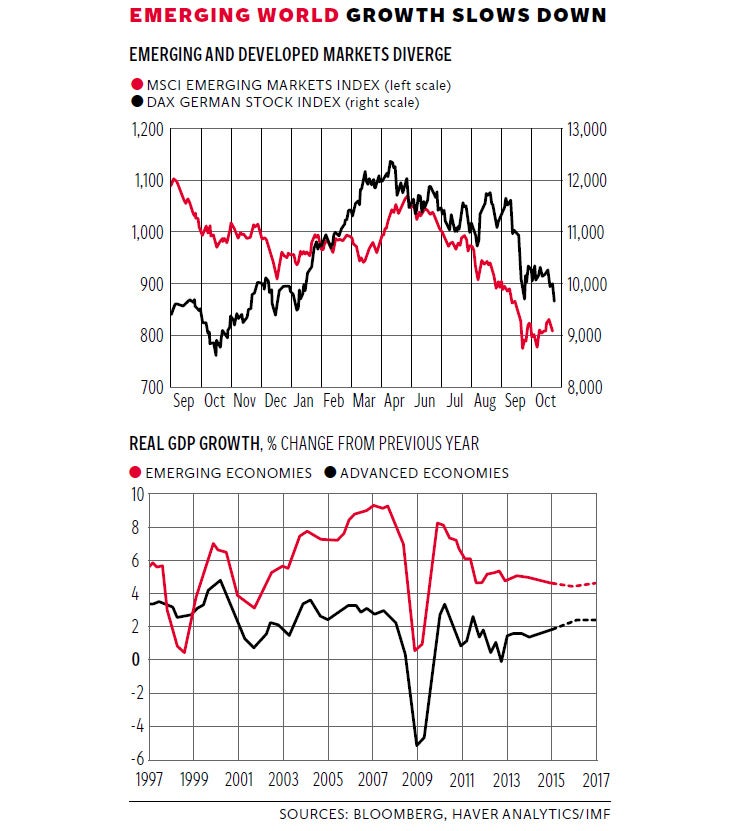

You can catch a feeling for the way in which emerging markets have led the developed ones down from the top graph (see above). It shows the MSCI index for emerging markets for the past 12 months, against the Dax index of German shares. I have chosen German shares as it is the most exposed of the G7 economies to a slowdown in China. As the evidence of a slowdown in China mounted, the emerging markets started to fall, but it was only this summer that German shares followed suit.

The weakness in the emerging markets may well persist. As Oxford Economics noted in a report, they have been hit by “an unpleasant cocktail of concerns over China’s growth prospects, sliding commodity prices and the looming onset of tighter US monetary policy”.

The contagion is already evident. I had not realised until I looked at the data quite how hard the decline in Chinese imports had hit both commodity suppliers and its regional trading partners. Standard Life does a weekly economic briefing and in the latest one it pointed out that coal imports were down 31 per cent in volume terms in the year to date, cotton imports were down 37 per cent, and vehicle and chassis imports were down 24 per cent. The regional impact shows in a fall of 14 per cent in imports from India, 10 per cent from Taiwan and the Philippines, and 6 per cent from Thailand.

Obviously within the developed world the impact is being felt in Australia and to a lesser extent in Canada, but elsewhere the picture is much more nuanced. For example in both the US and UK the fall in import prices may more than offset any decline in exports. Germany is more exposed (quite aside from the damage to its motor industry from the VW scandal) but even Germany is benefiting from the fall in import prices. Remember that Europe imports most of its energy needs.

It would be nice to draw up a tally of pluses and minuses, setting the advantage of lower input prices against the disadvantages of lower exports to the emerging world. But you cannot do it with any confidence. Even if your economic model accurately represented trade and financial flows, the data you would put into it not reliable. My guess is that the two broadly balance each other out, but that cannot be more than a pure guess.

Maybe the easiest way to see this period is not as a potential third crisis in a long drawn-out period of disruption, but rather as a return to more balanced global growth, with the emerging world still growing substantially faster than the developed world, but not racing ahead to quite the same extent. To get a longer view of relative growth rates, have a look at the bottom graph. This shows what has happened to the emerging economies and developed economies since 1997. For the past 20 years the only time when the latter grew faster than the former was during the brief period of the Asian financial crisis of 1997-08. Even then, the red line never dipped below zero, unlike the black line in 2008-09. Through the early 2000s the disparity between the two parts of the world became quite extreme, with the emerging world outpacing the developed two- or threefold.

Looking ahead are some IMF projections done earlier this year, which may now be a bit optimistic. But note how the gap between the two remains considerable. Even a slowing China and an India that is quite exposed to slower Chinese activity will still grow faster than any large Western economy. A glance backward to last year makes the point. The figures for UK growth look like being revised up yet again, probably to around 3.25 per cent, when the new stats come out next week. By developed world standards that is quite stunning, but is still only half that of China or India. You see the point.

There is one further twist here. Maybe the slowdown in China is not as serious as the markets expect. You cannot argue with the hard numbers of falling imports noted above, but maybe there are signs that the worst is past. Simon Ward, the economist at Henderson Global Investors, observes that the narrow money supply numbers in China have shot up in recent months, in contrast to decline monetary growth in the US. This may mean nothing – money supply jumps around. But there is at least a decent chance that the measures taken by the Chinese authorities to bolster confidence and increase demand might be working. The purchasing manager indices are weak, to be sure, but given the way China managed to maintain demand right through the big dip of 2008-09, it does not make sense to write off the effectiveness of its economic and financial policy now.

If this line of argument is right, then there is the Goldilocks scenario – a China, and a world, that will grow not too fast and not too slow, but at a sustainable rate. Because the growth will be slower, the present expansion phase can carry on longer than it otherwise would. I’m not saying this will happen; just that we should not dismiss the possibility of it doing so.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments