Are the market fears over blue chips’ dividend payouts a recession warning?

Economic View: There are three things we should look for in the coming months that will signal the turning point for shares

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What about dividends? They always matter, for on a very long view something like two-thirds of the return on equity markets comes from dividends rather than capital growth. They matter particularly at the moment because yield is the main thing holding up equities. So while they may not carry the glamour of the “buy” or “sell” recommendations the brokers put out, or attract the same attention, they are the anchor for the markets. Sentiment may be dreadful but dividends pay the bills.

There is however huge divergence between different markets, different sectors and different companies. Start with the FTSE 100, and you see an overall dividend yield of about 4.25 per cent. But that is held up by a handful of very large companies with yields that look unsustainable – or at least, that would be the inference the markets are drawing. We have just had BP holding its dividend, but the yield of more than 8 per cent shouts that it won’t be able to hold it for another year. Royal Dutch Shell, which has not cut a dividend since the Second World War, is on 9 per cent. HSBC is on more than 7 per cent. Some mining companies, such as Rio Tinto and Glencore, are on double-digit yields, while Anglo American, which has suspended its dividend for a year at least, is technically on a 25 per cent yield.

So the overall yield of 4.25 per cent may appear to be a support, but it is a somewhat bogus one. It is held up artificially by companies whose dividends are either unsupported by earnings, likely to be cut, have been cut, or even have been suspended. What should we make of all this?

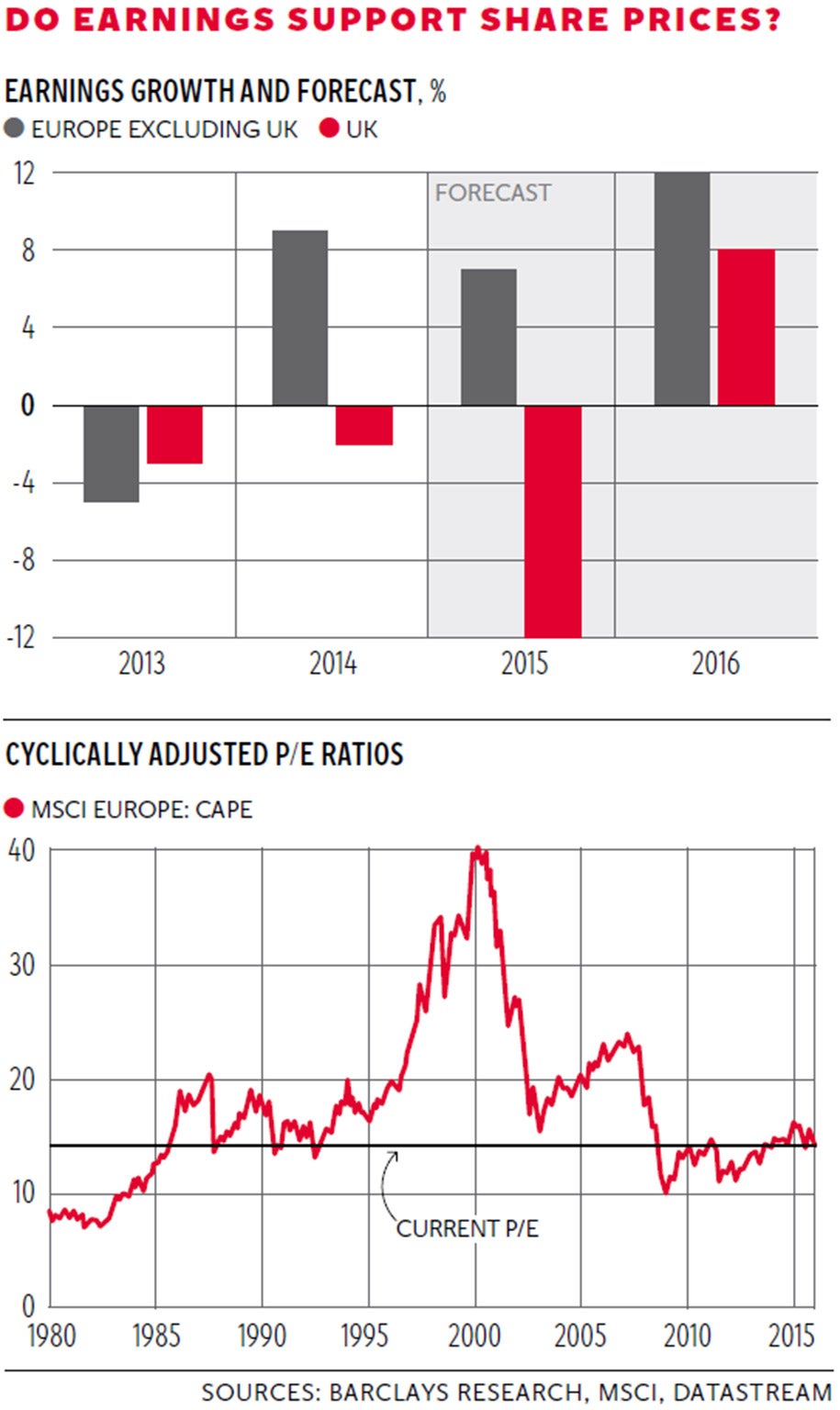

Well let’s start with earnings: if there are earnings that will either be paid out in dividends or eventually be reflected in the share price. The top graph, taken from some work on equity valuations by Barclays, shows the recent record of European and UK earnings plus some projections for last year and this – we haven’t really got into the reporting season yet, with things starting to pick up next week. As you can see, the UK story is not a pretty one, for we are skewed by the heavy weighting in banking, energy and resources. But the 2016 estimate is at least positive, which makes a change. European companies, by contrast, have both a better performance and a better outlook.

Barclays observes that earnings are the key and that must be right. It also notes that expectations at the moment are very low. Taking Europe as a whole (ie including the UK), the market’s earnings forecasts for 2015 are the second-lowest since 1989, while the weighting of portfolios in defensive shares is the highest since 1980. Companies don’t have to do very well to exceed expectations.

However, shares do not seem to be pricing in a serious recession. You can catch a feeling for this in the bottom graph, showing the cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio for the MSCI European index. We are not down in the bargain-basement levels of the early 1980s but we are absolutely not in the heady territory of 2000 or even 2008. Barclays observes: “Of course, in a full-blown recession, such as in 2008-09, valuations can head lower. Yet, without a recession individual stock multiples do now offer value.”

If there is going to be a recession, it will start in America. It has had the strongest recovery and, with the UK, capacity is tightest. The US labour market is beginning to feel tight, with unemployment down to 5 per cent, although we don’t know how many discouraged workers will be sucked back into jobs were it to tighten further. But recession? Consumer demand is all right, the housing market is all right, and service industries are seeing decent demand. Manufacturing may have softened a little and of course energy industries are seeing the impact of the oil and gas glut. But there isn’t the febrile “it’s different this time” atmosphere that normally precedes a recession.

So what should we look for in the coming months that will signal the turning point for shares? Three things. The first will be whether earnings this season outperform the low expectations that the markets currently have. They don’t have to be great to be better than expected, and any hint that those positive estimates for 2016 might look right would be enough to convince investors that a corner has been turned.

The second thing featured at the recent annual investment dinner for Schroders. It was whether and when value investment comes back into fashion. Nick Kerrage, co-head of Schroders’ global value team, observed: “In some ways, the worse things get the more positive I become. When things become savage, swift and emotional, and you get capitulation with large shares moving 10 per cent in a day, that’s when something irrational is happening. Typically that is building to an opportunity.”

He felt that in the next five years there was a great opportunity for value investing to outperform. All right, five years is a long time in markets, but the point is that the further out the turning point, the swifter the snap-around in values.

Finally, history is some sort of guide. Bear markets historically last between six and 18 months, or at least that is what would constitute a “normal” bear market. We are not quite nine months into this one, so you would not be expecting it to flip round just yet, though it is conceivable that we passed the bottom in those nervous days in the middle of January. If you look back, however, there is often some unconnected event, maybe a political one, that irrationally signals a turning point. Here is my suggestion. For UK and European shares the turning point will be the Brexit referendum, presumably in June – assuming, that is, that the answer is a remain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments