Hamish McRae: After the recent bull run, it wouldn’t be surprising if there was a correction in the markets soon

Economic View: The central banks have printed shed-loads of money and it has to go somewhere

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The “fear index” is creeping up. The trend of global interest rates is clearly up, with the possibility that one or two members of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee may vote today for a rise. And the fact that the Dow and the S&P 500 hit new all-time highs last week (the Dow going through 17,000) has, if anything, increased the sense of unease. This can’t go on, can it?

Of course no one can know. One of the embedded features of financial markets is that the sages on both sides – the habitual bulls and the habitual bears – are skilled at marshalling the arguments that support their case. But there are some observations worth making.

The first is that there is a clear difference between either side of the Atlantic. US shares have performed better than UK ones over the past year, with the S&P up 21 per cent whereas the FTSE 100 is up only 7 per cent – though if you adjust for the rise in sterling against the dollar, up 14 per cent, the discrepancy disappears. However, on a longer view the FTSE 100 index has underperformed as it remains below its all-time high at the end of 1999 and, more important, is less demandingly rated. It is on a price-earnings (P/E) ratio of around 14, whereas the S&P P/E ratio is just under 20. (These are so-called trailing P/E ratios. If you take forward P/E ratios, which are based on expected company earnings rather than the most recently reported ones, the numbers are lower.)

The second point is the fear index, the Vix (which tracks volatility in US share prices), is still very low by historical standards. What it does is to show the cost of covering against a fall in the market, relative to the present level of the market. At the time of the financial crisis it shot up to 80; a couple of weeks ago it was down below 11, the lowest ever. This week it has climbed to just under 12, so the rise could be seen as a healthy awareness that markets do sometimes hit bumps rather than anything untoward. Shocks by definition are unpredictable, and a gradual climb in bond yields is already in the market. But the obvious potential shock out there would be were that climb to be faster than at present projected.

The third point is the scope for higher company earnings – or profits in UK parlance. In the US the share of GDP going to company earnings is historically high, so while reasonable growth should ensure a continued climb for another couple of years, there is an inherent weakness there. The consensus is that earnings will be up by more than 10 per cent this year but the next few weeks will be important to see if companies are doing as well as expected.

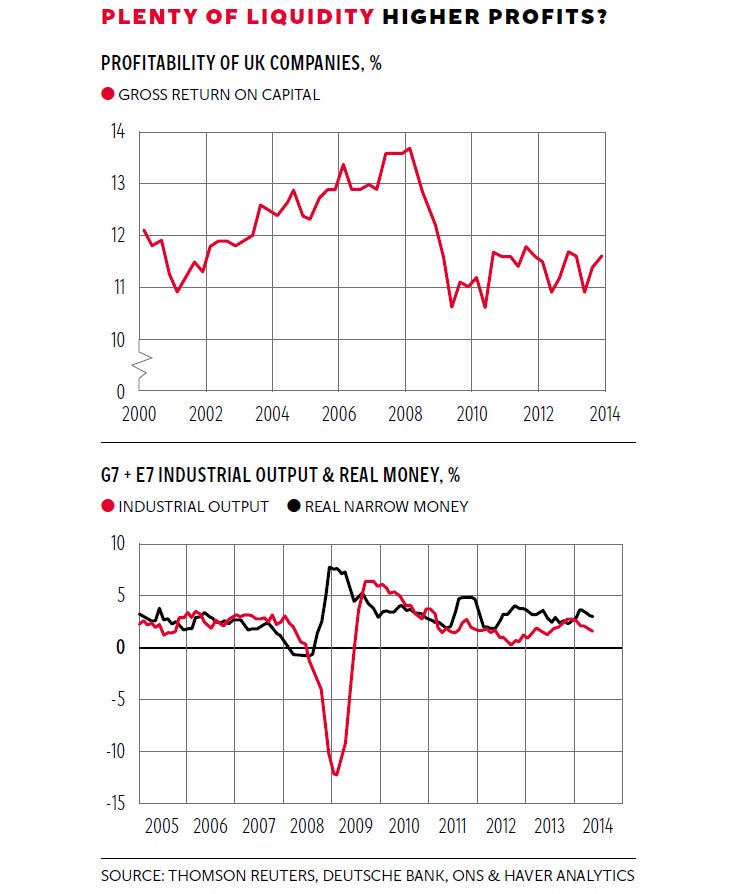

In the UK the outlook is, if anything, even more positive, particularly for domestic earnings. There is a bit of a puzzle as to whether company earnings are high by past standards or merely reverting to normal. I find the top graph interesting, as if you are interested in profits in relation to capital, they are still below the average level through the early 2000s, and well below the 2007-08 peak. A commonsense assessment of that would be that profits should be sustainable at present levels and there may be scope for them to creep up a bit.

Finally, there is the wall of money argument. The central banks have printed shed-loads of money and it has to go somewhere. Some has gone into property and you are starting to hear of worries in the US that residential house prices may be becoming a bit of a bubble, just as you hear that same story here. Rob Wood, a former Bank of England economist now at Berenberg, notes that the Bank has a high tolerance for house-price inflation and expects prices to rise a further 10 per cent this year and next.

If easy money has boosted residential property it surely must also have been a factor boosting other asset prices, notably equities. The bottom graph shows what has happened to industrial output and real money supply in the G7 and the E7, the latter being the seven largest emerging economies. It comes from Simon Ward at Henderson, who argues that the increase in global money supply underpins the rise in global output. There is the further point that if money supply exceeds output that also underpins global asset prices. You don’t need to be a paid-up monetarist to see some merit in that argument. Or to put the point in more negative terms: if asset prices do start to fall it won’t be because of any shortage of cash swishing around the world. It will be some other shock that we cannot at the moment anticipate.

My own view, for what it is worth, is that after an extraordinary bull run such as we have had, it would not be at all surprising if there were some sort of correction in the months ahead. We may have begun one now. If we have, that will give succour to the habitual bears, and we are beginning to hear growls.

But given the extreme unattractiveness of bonds, and given reasonable growth in corporate earnings, global equities qualify as a reasonably attractive investment even at these levels. Besides, what else do you do?

I suppose the core argument supporting global equities is that the world is still in the early stages of a long economic upswing. The fact that the recovery has been relatively disappointing and the fact that it started from such a low base are positives, not negatives. They mean that the growth phase can carry on for longer. That is not a very sophisticated argument and it assumes that everything reverts to a mean: eventually all or at least most of the growth that has been lost will be recovered. But there is a crude logic to it in these uncertain times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments