Infrastructure projects often struggle to meet expectations: poorly managed geo-risks are a factor

THE ARTICLES ON THESE PAGES ARE PRODUCED BY BUSINESS REPORTER, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CONTENTS

Fugro is a Business Reporter client.

Most major infrastructure projects fail to meet cost and schedule expectations for all sorts of reasons. Contractors go bust, natural disasters strike, inflation bites costs, and broader political circumstances become unfavourable to the project’s aims.

In the energy sector, 90 per cent of projects run over budget. And while coverage of this tends to focus on the headline issues – namely, political and economic instability – less attention goes to an area that has proven time and again to be a headache for investors, engineers and all manner of stakeholders: geo-risk.

Geo-risk is about uncertainty in the state and behaviour of the environment and processes within it, and also how the natural environment interacts with the structures built on top of it or in it, and the risks that result. It’s a vital factor and that’s why all natural-resource-focused projects involve ground exploration to inform design and construction, whether it be onshore or offshore. If problems in the ground and broader environment are not identified and dealt with, then significant time, money and resources are wasted, the quality of the surrounding environment is jeopardised, and even property and human life can be affected.

Identifying geo-risks doesn’t only help mitigate these issues. It also means a project can be made safer, more insurable and less expensive – and, says Rod Eddies, Solutions Director Land Site Characterisation at Fugro, it can ensure shorter timelines. Not only that, says Eddies, but shorter timelines “mean less uncertainty and better managed risk – and, ultimately, use of fewer materials leading to more sustainable outcomes.”

Fugro, whose advanced technologies mean it can generate detailed insights relating to geo-risk, works closely with clients right from the project conception stage to determine objectives and assess what risks it faces in the ground and broader environment. This work needs to be done even before any design takes place, lest the client either over-engineers or under-engineers an asset, eroding value right at the beginning of the project life-cycle.

Take a tunnelling project, for instance. There have been cases in which boring machines have gone to work before adequate risk assessment has been carried out. They’ve hit unexpected ground conditions, and the machinery has gotten stuck, thereby delaying the project for months. Budgets have been blown, and reputations – as well as expensive machinery – have been damaged.

Worst of all, assets are delivered late and over budget.

Shortening project life cycles, reducing costs

Eddies identifies another problem that causes inadequate understanding of geo-risk. “If we have insufficient understanding of the subsurface, we’re forced to make assumptions,” he explains.

“And if we’re forced to make assumptions about subsurface conditions, for example, that leads to overly heavy engineering in geotechnical design. This is understandable, of course, as assets need to be primarily safe and dependable. But with excessive conservatism comes additional time, comes additional cost, comes additional resources.

“This isn’t the right direction for a sustainable future because we’re looking to shorten schedules, reduce costs and use fewer resources.”

Fugro recognises that time stress is also a major factor in infrastructure development. Shorter timelines mean less uncertainty and less risk.

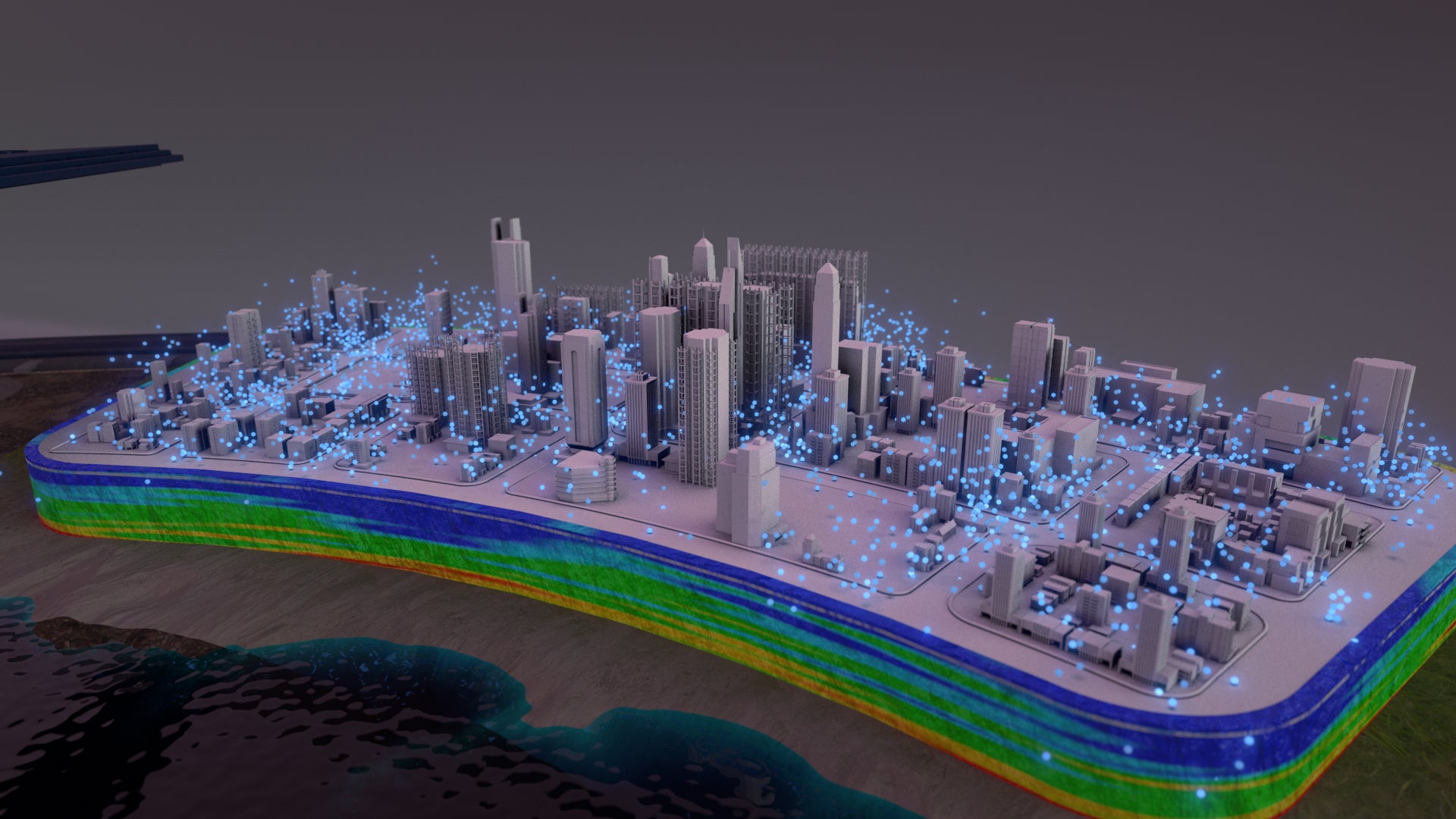

That’s why it has developed the Geo-Risk Management Framework, or GRMF. The GRMF is founded on the principle that by reducing uncertainty we can better manage geo-risk. It takes a whole-lifecycle approach, managing geo-risk right from the start. In parallel with this, the use of emerging geophysical screening technologies, artificial intelligence and digital modelling can build a much better representation of the ground, components of an overarching digital solution rather than just stand-alone services, and deliverables that provide insights for specialists and non-specialists alike.

But it goes even further. Geotechnical design codes are evolving, but slowly compared with the rapid technological changes and digital revolution. Eddies sees a need for companies such as Fugro to influence these codes to build both acceptance and adoption of better ways to represent the subsurface.

Fugro knows it couldn’t have got to where it is without looking at, and borrowing from, other sectors. One might liken the effects of geo-risk surveying to an MRI, whereby early screening becomes hugely beneficial in addressing problems that, if left unidentified, could be costly. It knows to look outside its own areas of expertise – even to an area, such as medicine, that has little obvious application to its own. This gives Fugro a better view of that important, and often overlooked, feature of infrastructure projects: the ground.

“Better representation on the ground means fewer design assumptions and construction surprises,” Eddies reiterates. And the knock-on effects all lead to one end-point: “More sustainable outcomes for a safe and liveable world.”

For more information please visit www.fugro.com.

You can check out more episodes from this series below: