Mobile operators need to invest now to make the most of the next phase of 5G

THE ARTICLES ON THESE PAGES ARE PRODUCED BY BUSINESS REPORTER, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CONTENTS

Delta Electronics is a Business Reporter client.

5G has grown quickly in low- to mid-band spectrums, but its real potential is in high-band connectivity with ultra-low latency, which is hampered by costs and lacks a booster application.

Today, 5G networks cover on average 81 per cent of the populated areas in Europe, with countries such as Germany well above 90 per cent and the Netherlands and Italy close to full coverage. The MENA region is also scaling up and, by 2030, the Gulf Cooperation Council states are expected to have the widest 5G coverage in the world, at 95 per cent, overtaking the current leaders, Asia and the US.

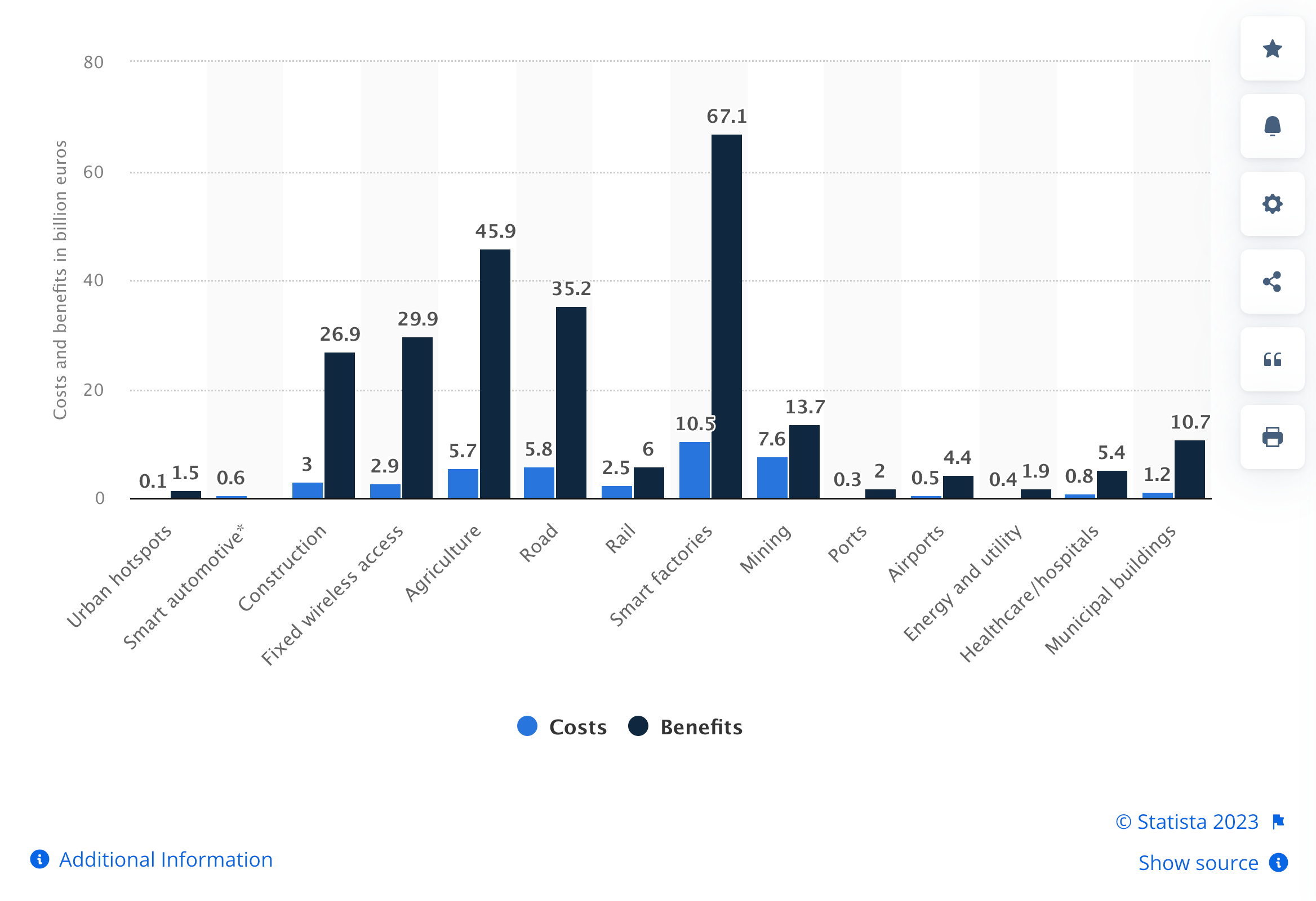

But this success story hides an uncomfortable truth: much of the current coverage is in the low and mid-band spectrum, when the real promise of 5G lies in high-band connectivity providing latency of less than 1ms. It is those high-speed connections that will enable applications such as self-driving cars and real-time internet of things tools for smart factories.

Getting networks ready for high-band 5G will require investments in the hundreds of millions of dollars, including making the necessary adaptations to power infrastructure and tower sites – not to mention the added pressure to cut CO2emissions.

Here, Andreas Grewing, Vice president, Telecom Power Solutions at Delta Electronics EMEA Region, outlines how operators can meet the triple challenge of reshaping their infrastructure while lowering CO2emissions and finding the booster application to make their investments worthwhile.

Where is 5G now?

The low- and mid-band rollout of 5G has progressed quickly. Low-band 5G spectrum (below 1Ghz) offers blanket coverage over wide areas but at slower speeds, while mid-band 5G (up to 6Ghz) provides a balance of speed and coverage to serve large amounts of users. But the real value of 5G is in the high band, between 24-40GHz.

High-band 5G uses millimetre wave spectrum to deliver speeds of 3Gbps and more, but it has limited range and can be blocked by obstacles such as trees and buildings. Its smaller coverage area requires more cell sites and upgrades to the Radio Access Network (RAN) and tower infrastructure.

Mobile operators are now facing a chicken-and-egg scenario. Typically, they want to see a return on investment over three years, but at present, few if any applications are available that can make use of high-band 5G.

Traffic control and smart energy distribution systems are still in the early development stages. Highly automated vehicles will make an impact from 2030 onwards, but fully automated driving will come much later.

When that happens, it will greatly depend on the availability of high-band 5G and future 6G networks to give cars the ability to react to traffic in real time.

This puts the onus back on operators and leaves the market at an impasse.

How does the power infrastructure have to change for “real” 5G?

To move forward with 5G high-band deployments, the passive infrastructure of the RAN needs a fundamental upgrade.

Data needs to be processed with low latency, meaning data centres needs be installed near the network antennas. Putting a complete micro data centre, even if it is a compact one in a container on a rooftop – which is where many antennas are located – is already a challenge. Adding to this, typical server backup systems allow only 30 minutes of failover time. In the future, up to 48 hours will be required to keep applications such as self-driving cars online until normal operation can be restored at a site.

At the heart of the issue is upgrading the tower infrastructure, which will see the current 48V DC power setup replaced by small EDGE data centres, a small data centre that is located close to the edge of a network. These new set-ups which is very close to the antenna will manage network resources and with this data processing locally, close to the end-user.

How can mobile operators make the energy transition?

Another factor to account for is higher energy consumption — much higher than today — at odds with the mandate to save energy and lower CO2 emissions. While 5G is less power-hungry than earlier generations of telecom equipment, it could end up drawing a lot more energy than 4G. The Financial Times reports that the increase could be as much as 140 per cent, simply because of the high number of cell towers and escalating data volumes.

Delta has been offering high energy-efficient rectifiers reaching 98 per cent efficiency. The other alternative is moving to renewable energy. Many major telecoms operators have already managed to cut their greenhouse gas emissions by more than 90 per cent by buying-in renewable electricity energies and rolling out more energy-efficient infrastructure.

As a next step, operators need to look at using solar and wind directly – for example, on the tops of EDGE data centre containers, cabinets or buildings. A hybrid energy-saving solution by combining solar, wind power and fuel cells can be the ideal solution to the real energy saving future.

Where do tower companies come in, and how does it affect the 5G development?

One solution to all these challenges may lie in the growing role of tower companies.

Traditionally, telecommunications companies have owned their masts and towers, but in recent years, many of them have divested their passive network infrastructure assets to dedicated tower companies. TowerCos, as they are known, acquire and manage these assets and lease them back to mobile network operators.

As dedicated providers, TowerCos benefit from scale economies and other efficiencies. For operators, selling and leasing back their tower infrastructure turns a business area heavily geared to capital expenditure into a more manageable operational cost. Moreover, technology and investment risks – including those associated with the move to high-band 5G – move to the TowerCo. Thus, TowerCos should find the technologies required for high-band 5G are mature and that they can draw on power infrastructure suppliers such as Delta for an efficient transition.

What technology can’t resolve is the lack of content that leverages high-band 5G capabilities and brings in customers. With 3G and 4G, content was largely delivered by over-the-top providers such as Netflix, Apple and Amazon, at the expense of mobile operators. This trend is likely to continue, and operators will need to find other sources of monetisation.

One of these could be network slicing, which enables the physical network to be divided into multiple virtual networks for different users and applications. Each slice can have its dedicated security levels and performance characteristics, tailored to what customers require, whether it’s ultra-fast connections for autonomous vehicles or highly secure, wide-area network services to replace traditional Wi-Fi for businesses.

“Mobile network operators must adopt a ‘build it, and they will come’ approach if they don’t want to lose out to others ready to grasp the 5G opportunity,” said Grewing.

For more information, visit delta-emea.com.