‘We literally don’t get time to take breaks’: How staff shortages are affecting hospitality workers

Unions say hospitality must become a ‘high-wage, high-value sector’ to attract workers

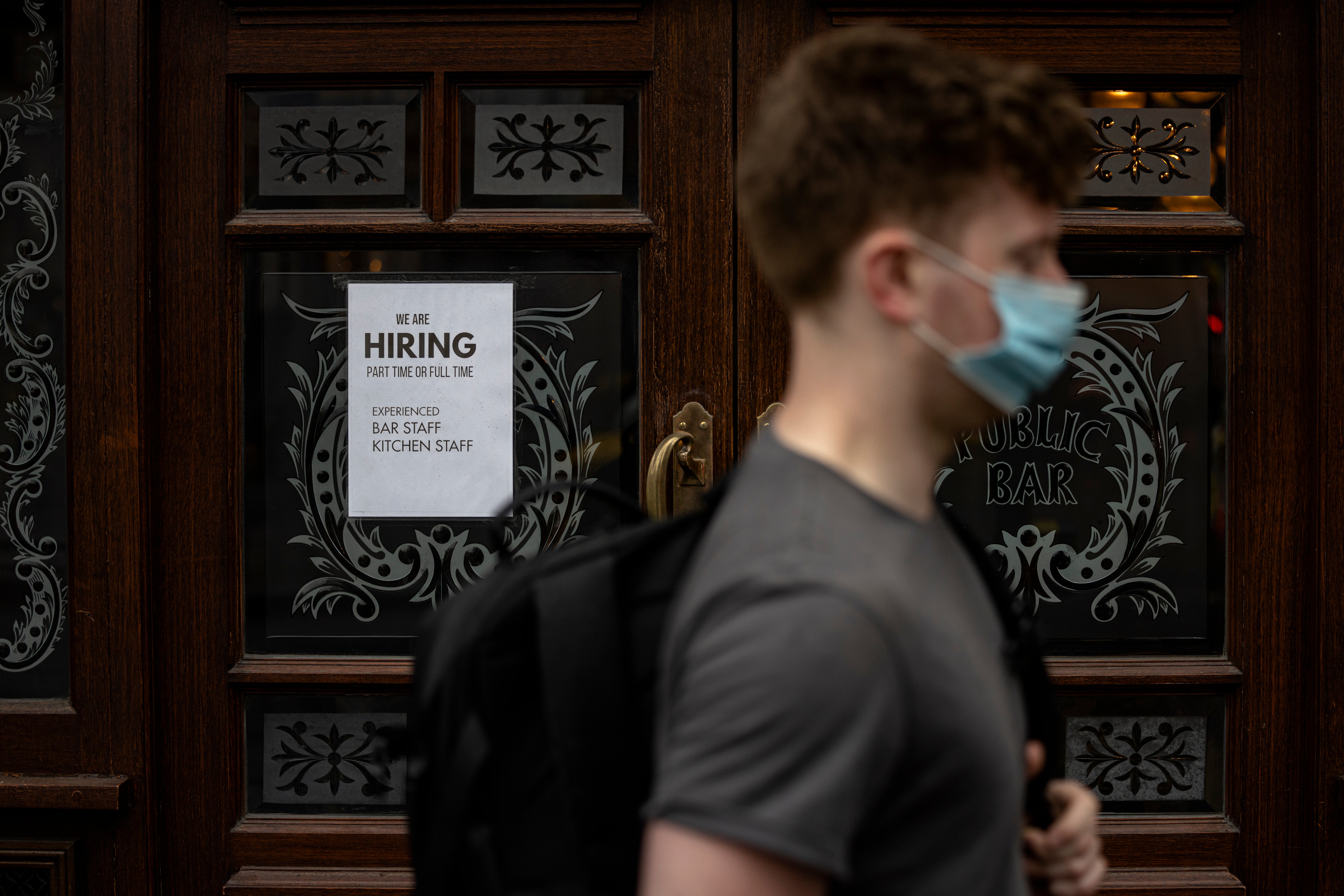

As customers began frantically booking tables of six in pubs and restaurants following months of lockdown, workers were leaving the hospitality industry in droves.

Brexit and the pandemic have deepened longstanding issues in parts of the sector, leading unions to call for improved wages and working conditions in order to attract and retain staff. Meanwhile, workers remaining in the industry are bearing the brunt of labour shortages, describing chaotic shift patterns and spiralling workloads as they struggle to keep up with demand.

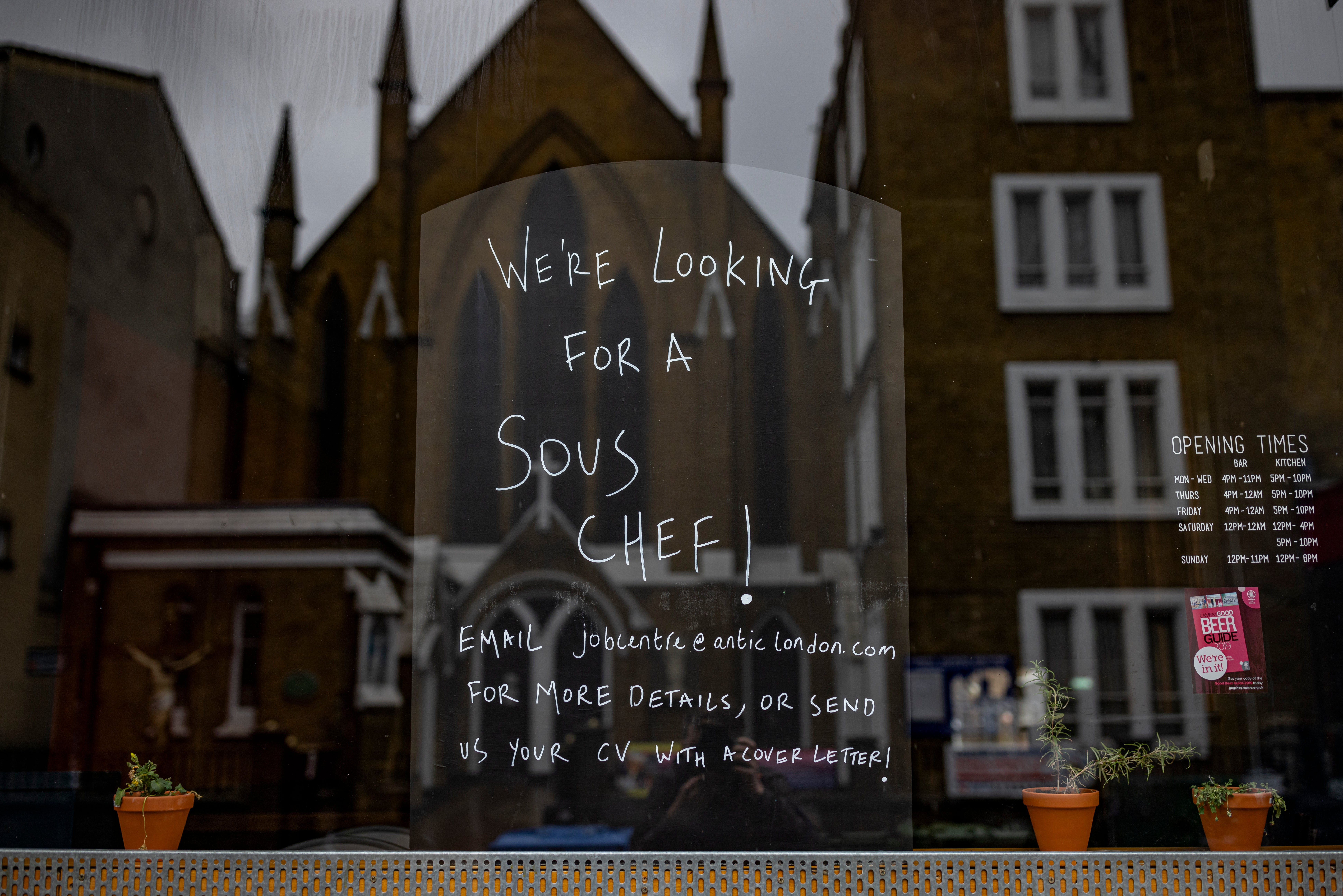

Restaurants and pubs have said that up to a quarter of those employed in the industry before the pandemic will not return, leaving many venues struggling to recruit skilled staff. According to trade body UKHospitality, 85 per cent of venues are looking to hire chefs, while 80 per cent need front-of-house staff.

Kevin, a head chef at a major hotel group in the east of England, says the situation is approaching a “crisis point” in his kitchen.

“The pressure is insane. Because you’re short-staffed all the time, the workload just goes through the roof. There’s just zero understanding of that,” he says. “Stress during service has been so mental that this week I had two chefs walk out, two days in a row – one left in tears and the other stormed out in a rage. The team are at breaking point, quite frankly. I saw one chef in tears practically the entire day.”

Although the pandemic has exacerbated the issue, Kevin says the problems in his workplace are longstanding. “The chef shortage issue has come to a head, but it’s been going on for years. Obviously, the more chefs leave the sector, the more that puts pressure on those that are still here.”

He thinks that the pandemic has led many chefs to reappraise their career choice. “They’ve gone off to do other things, even if it’s working in retail, or driving Tesco delivery vans, purely because they get a better work-life balance and don’t want to be breaking their neck for a pittance any more,” he says.

Meanwhile, an assistant manager at a pizzeria chain in the east of England tells The Independent that the restaurant he works at is operating with 50 per cent of its usual staff; he estimates they have about one waiter for every 20 tables.

“At the moment, I’m kind of everything,” the assistant manager, who does not want to give his name, says. “When the weekend hits, we literally don’t get time to take breaks – there’s constantly a queue at the door.

“There’s no potwash on throughout the busy times – it’s just someone absolutely random, front-of-house or a manager, but whoever goes and does it makes the floor short.”

The labour shortage is also affecting shift patterns. One waiter at a private members’ club in London tells The Independent that staff are being made to work split shifts that eat up their entire day. Prior to the pandemic, employees would work an early or a late shift. Now, they’re being asked to work the busiest hours of a morning service, and then come back to cover the dinner period in order to stretch out the limited number of employees.

“There’s not much you can do. You work in central London. You don’t live in central London. You can’t go back home,” says the waiter, who does not want to provide his name, adding that his “body clock is all over the place”.

Also in London, a manager at a high-end hospitality group says that one of the company’s 400-room hotels is being run by just three members of staff nightly.

“The workload is getting bigger for the same number of people. So we have one person during the day, and two people during the night, and everything has to be done. We have to achieve the targets,” the manager says, adding that they have about half the number of staff they had before the pandemic. “One of the other managers said to me, ‘I’m dying here, trying to cover room service with three members of staff,’” he says.

The manager, who asks to remain anonymous, says the group has recalled staff it made redundant in September, only to offer them severely reduced hours, leading several to walk out of the meeting. Most of the hotel’s former team members were foreign nationals, and many have not returned to the UK after travelling to their home countries during the pandemic.

National secretary of the GMB union, Andy Prendergast, says the pandemic has “just exacerbated” a problem caused by Brexit. “Employers need to work with unions to deal with the long-established issues within the industry, such as the perceived lack of status, lack of career opportunities and unsociable hours, to create a more attractive career for workers moving forwards.

“The truth is that in the short term, coronavirus isn’t going anywhere, so even if the government changed immigration rules, in the world of closed borders we’re not going to be able to attract migrant workers any time soon. The only sustainable plan is to make hospitality a high-wage, high-value sector, with better-quality jobs.”

Bryan Simpson, an industrial organiser for Unite, also stresses that the sector needs to make itself more attractive to workers in order to attract back talent. “The double whammy of Brexit and a pandemic has left hospitality chronically understaffed, with 48 per cent of our chef members reporting that they plan to leave the industry within the year,” he says. The union is calling for the sector to pay a real living wage, end zero-hours contracts, and enact a sexual harassment policy.

After years working in hospitality, the waiter at the members’ club is considering leaving the industry altogether. “I’ve had enough,” he says. “There’s been no pay rise in two years, constant staff shortages and toxic shift patterns.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments