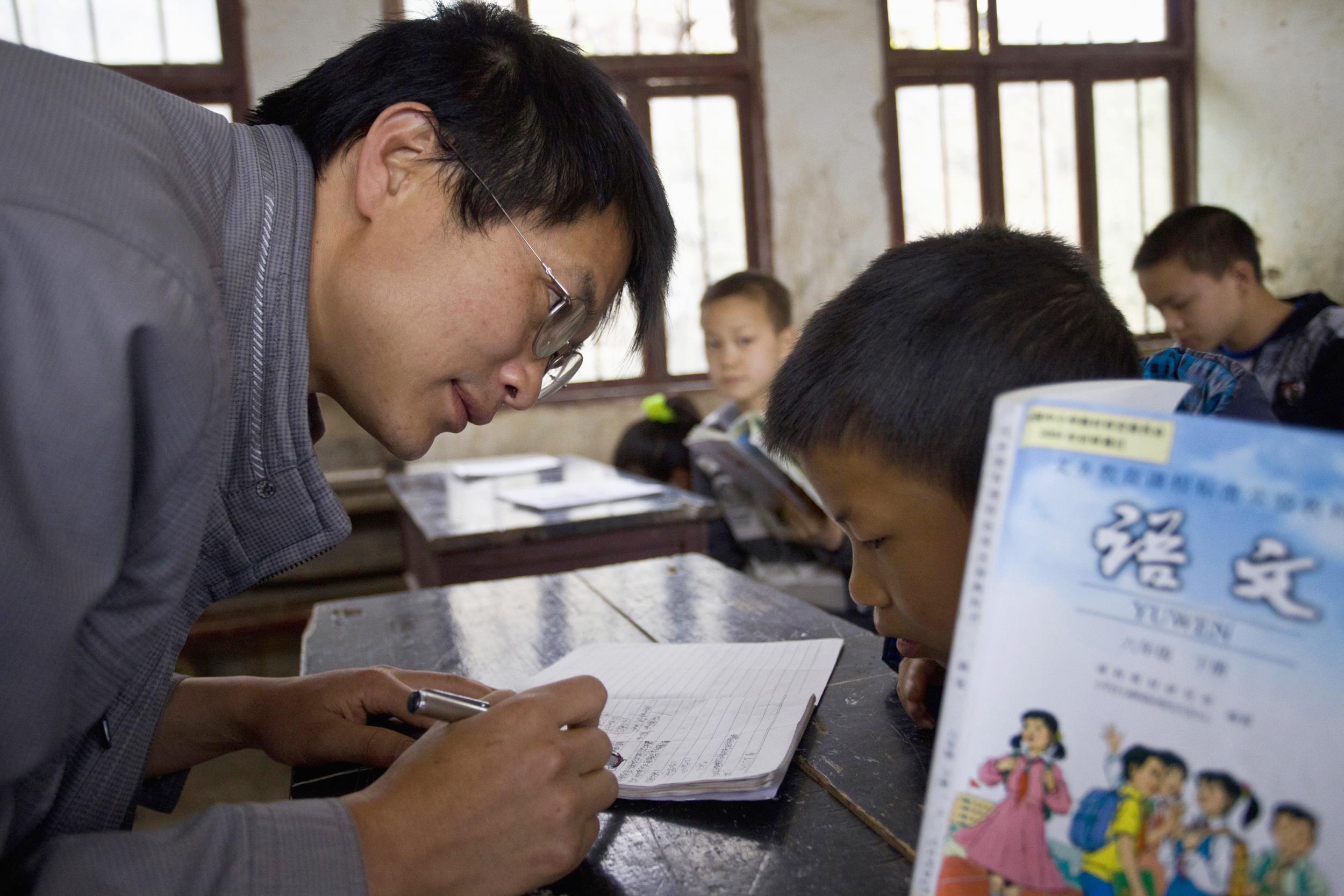

Virtual American tutors are helping Chinese kids to learn English

Online schools battle with traditional schools for supremacy in an $80bn market

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hardly anyone bothered to learn English when Wu Wenhua was growing up in 1980s China. But now that she has an 11-year-old son, Wu believes knowing the language is key to opening doors.

So Wu, 38, signed Ryan up for an online service, called VIPKid, that connects Chinese primary school kids with US teachers for one-on-one classes.

With Ryan now top of his class at school, Wu is satisfied – or at least as much as a hard-charging Beijing mother can be.

“He recently got 99 out of 100,” she says, grimacing slightly. “He does pretty well.”

Parents like Wu are fuelling an education boom in China that’s having global repercussions. Millions of children are pouring into classes for English, maths and the sciences to gain the skills they need in a knowledge economy.

Chinese parents have always prioritised academic achievement; now, they have the means to invest in extra-curricular education, propelling a domestic market that UBS says will double to $165bn (£124bn) within five years.

Leading players such as New Oriental Education & Technology and TAL Education have gone public in the US and seen their shares soar.

Now, online startups are gaining ground with parents who grew up in the internet era and see advantages in digital learning.

Beijing-based VIPKid has expanded to 200,000 students, and just raised venture money at a valuation of more than $1.5bn from Sequoia and Tencent.

Shanghai rival iTutorGroup has won backing from Chinese internet giant Alibaba and Qiming Venture Partners.

(The online education clash is yet another proxy battle between Alibaba and Tencent, which have squared off in almost every fast-growing tech sector.)

“Chinese parents have high expectations for their children; everyone wants their kids to get into Tsinghua or Peking University,” says Edwin Chen, an analyst with UBS Securities. “This is creating huge demand.”

In the West, early efforts at online education floundered. The technology wasn’t good enough, and there was significant institutional resistance.

Many are yet to be persuaded that digital instruction can replace the traditional classroom.

In China, however, a combination of factors have given online schools a boost. Finding good teachers can be a challenge, especially in subjects like English and in places beyond the biggest cities, while internet access and mobile services have spread widely.

For the nation’s education-obsessed tiger mums and dads, it’s worth the risk to prepare their kids for a high-tech future.

Sceptics believe online education will probably remain a small part of the overall industry.

But Curtis Johnson, an author who has championed online teaching, is convinced that global adoption is coming, owing in part to experiments in nations like China.

“This is just as inevitable as watching movies or listening to music or reading the news online,” says Johnson, who co-authored the book Disrupting Class with Harvard University’s Clayton Christensen in 2009.

Chinese parents currently pay for fewer extra-curricular classes than their Asian neighbours.

Last year, about 37 per cent of kids in China received tutoring, compared with the 70 per cent in places like Japan, Taiwan and South Korea, according to UBS.

But the research firm projects that ratio will hit 50 per cent in five years, during which time the Chinese government expects the number of kids attending nursery through to the final year of secondary school to swell to almost 200 million.

Traditional tutoring companies, with brick-and-mortar classrooms, are already cashing in.

New Oriental, founded by Peking University professor Minhong “Michael” Yu in 1993, is projected to reach revenue of $2.2bn in the current fiscal year.

TAL Education, which opened its doors about a decade later, now has more than 500 learning centres in about 50 cities and is expected to boost revenue to $1.7bn this fiscal year.

VIPKid has set itself apart by recruiting American teachers and positioning its services as similar to the education in top US schools.

Cindy Mi, the startup’s 34-year-old founder, argues that teaching online allows the kind of data analysis and scientific review that will lead to fundamental improvements in education. She’s now expanding internationally and bringing her approach to the US.

The Beijing-based startup has become one of the fastest-growing companies in the industry, with revenue on pace to reach 5bn yuan this year. Many Chinese parents see advantages in learning online.

For one thing, they don’t have to drive their kids to a classroom across town. For another, there are bragging rights associated with hiring an American teacher.

Gong Aihua, a 35-year-old mother in the southern city of Shenzhen, heard parents were placing their kids in English class even before they started primary school.

She didn’t want her only son to fall behind. She checked out VIPKid’s videos at the suggestion of a friend and then booked classes for her child, Noah, who was four at the time.

“Right now it seems that all the kids are learning English,” Gong says. “I’d say about 50 per cent of my friends are sending their kids to English classes.”

Offline schools are slightly more expensive, but what she really likes about online classes is all the data.

“With VIPKid, you can see what your kid has learned, what needs to be improved and you can understand his progress,” she says. “At other schools you can’t fully grasp the situation.”

Noah, now five, usually takes classes three times a week. The lessons take place over a video conferencing system: student and teacher can see each other in squares on the right-hand side of the computer screen; both work on a digital chalkboard to the left.

In one recent class, Yasche Glass, a teacher who lives 8,000 miles away in Jersey City, New Jersey, shows him a picture of a girl pointing to different parts of her head.

“Ears, mouth, face, eyes, nose, uhhhh…”

The tiny boy freezes.

“What is it?” Yasche asks. “No, up here.”

“Hair!” the boy shouts with glee.

“Good job, Noah!” Yasche says, laughing.

VIPKid’s growing popularity has not gone unnoticed. New Oriental and TAL Education have both been pouring money into online courses and highlighted these investments on earnings calls.

iTutorGroup, which began with adult education online, relaunched its services for nursery through to secondary school under the VIP Junior brand in January.

Ads featuring basketball star and sponsor Yao Ming are plastered all over buses in Beijing and other major Chinese cities.

iTutorGroup, which also counts Goldman Sachs and Temasek among its backers, was founded in 1999 and reached a valuation of more than $1bn in 2015.

It’s determined not to fall behind a company 14 years its junior. “We are the first to have a 24/7 proprietary network for teaching online,” says Paul Keung, the chief financial officer. “We also don’t limit you to teachers in the US. We let you connect with great native speakers all over the world.”

To stay ahead of rivals, VIPKid has set up a research institute tasked with making online teaching more effective.

Leading the effort are Rob Hutter, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist, and Bruce McCandliss, a professor at Stanford’s Graduate School of Education.

“Great technology companies are products of evolutions, paradigms, tipping points,” Hutter says.

“VIP is no different. We’re at a moment where we can replicate the benefits of live [classes]. But in addition, we can actually make it better.”

With some 2 million classes offered each month, VIPKid offers researchers a vast trove of data to analyse. In the past, McCandliss says, studies of education techniques were limited to dozens or scores of pupils.

“Now you have hundreds of thousands of students working with thousands of teachers,” he says, which makes it possible to home in on specific details – syntax, vocabulary, accent – and fine-tune lessons for individual students. Eventually, McCandliss says, the immense data-crunching power of artificial intelligence could be unleashed on web learning.

That future is probably years off. In the meantime, startups like VIPKid have to prove they are more than a passing fad. Already, some Chinese parents are souring on the experience. Jean Liu tried several online schools and then moved her eight-year-old daughter back to the classroom.

The Beijing mother noticed that services tend to deploy their best teachers in ads and introductory courses. But once you sign up, she says, the “good teachers aren’t usually available”.

Jean also thinks it’s difficult for youngsters to sit in front of a computer for a whole hour. “You can’t really make it too difficult, especially for young kids,” she says. “Offline, you can do much more: kids can break up into groups and act out the stories they just heard, for example.”

And while many parents like VIPKid’s one-to-one teacher-student ratio, as the startup signs up more kids it faces a challenge in lining up enough instructors to teach them. Chen, the UBS analyst, questions whether the business model can ever be as robust as one teacher leading a group of paying students.

“It’s difficult to scale up because one teacher can only teach one student at a certain period of time,’’ Chen says.

Mi is undaunted. She says there are millions of qualified US teachers who have left the profession or are looking for extra work, so shortages are not a concern. Her company just raised $200m, allowing her to step up investments in marketing, engineers and research.

Perched on a couch at her overcrowded office in a former Taoist temple, she ticks through all the new features and products the company is introducing: a teacher recommendation service much like the one Amazon uses to suggest movies, a star system so parents can rate those teachers and data analysis that tells parents how their kids are progressing.

Mi expects to sign up 1 million students by 2019 and says 10 million is probably not that far off. “Our vision is to be the best K-12 education globally,” she says. “Over the long term, this can go beyond anything we can imagine.”

Bloomberg

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments