Venezuela: How the most oil rich nation on earth was brought to the brink of collapse

This is what happens when an economy and a society disintegrates due to economic mismanagement and populist folly

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Venezuela’s president, Nicolas Maduro, took a highly risky decision this week. Not debasing the currency. Not rigging an election. Not ordering the arrest of opponents. He’s done all that already and survived.

No. What Maduro did was to announce plans to rein in fuel subsidies. “Gasoline must be sold at an international price, to stop smuggling to Colombia and the Caribbean,” he explained in a televised address.

Normally, ending such distorting subsidies is precisely what economists would recommend. But in a country like Venezuela it’s a political gamble with the highest possible stakes.

Removing the subsidy will instantly hit millions of working Venezuelans. And fuel has been one of the few costs that has remained relatively stable amid the country’s hyperinflation of recent years.

A similar hike in domestic fuel prices by former president Carlos Perez in 1989 ignited mass riots and brutal repression in the capital city in an incident known as the Caracazo, or “Caracas smash”.

It was followed by an attempted coup.

So making fuel more expensive is not a decision any Venezuelan leader would take except in the most extreme circumstances.

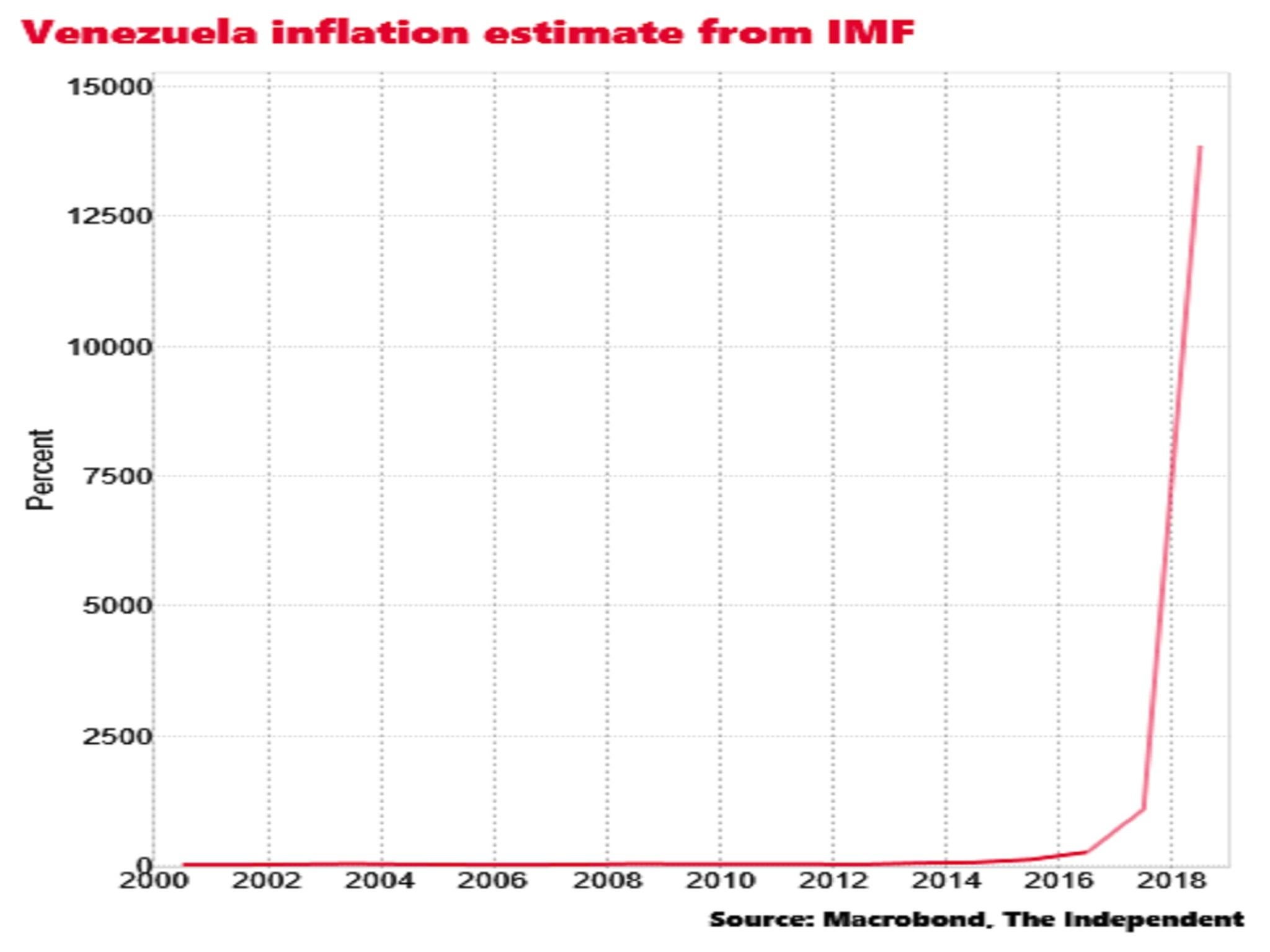

The reality is that Venezuela is more or less out of options. Prices are estimated to be rising at a rate of 3 per cent every day, giving an annual inflation rate of more than 40,000 per cent and an International Monetary Fund official has warned the rate could reach 1,000,000 per cent by the end of the year.

That would be one of the most disastrous episodes of hyperinflation in history, up in the pantheon with Zimbabwe’s currency collapse in the late 2000s under Robert Mugabe, and Germany’s descent into monetary hell in the 1920s.

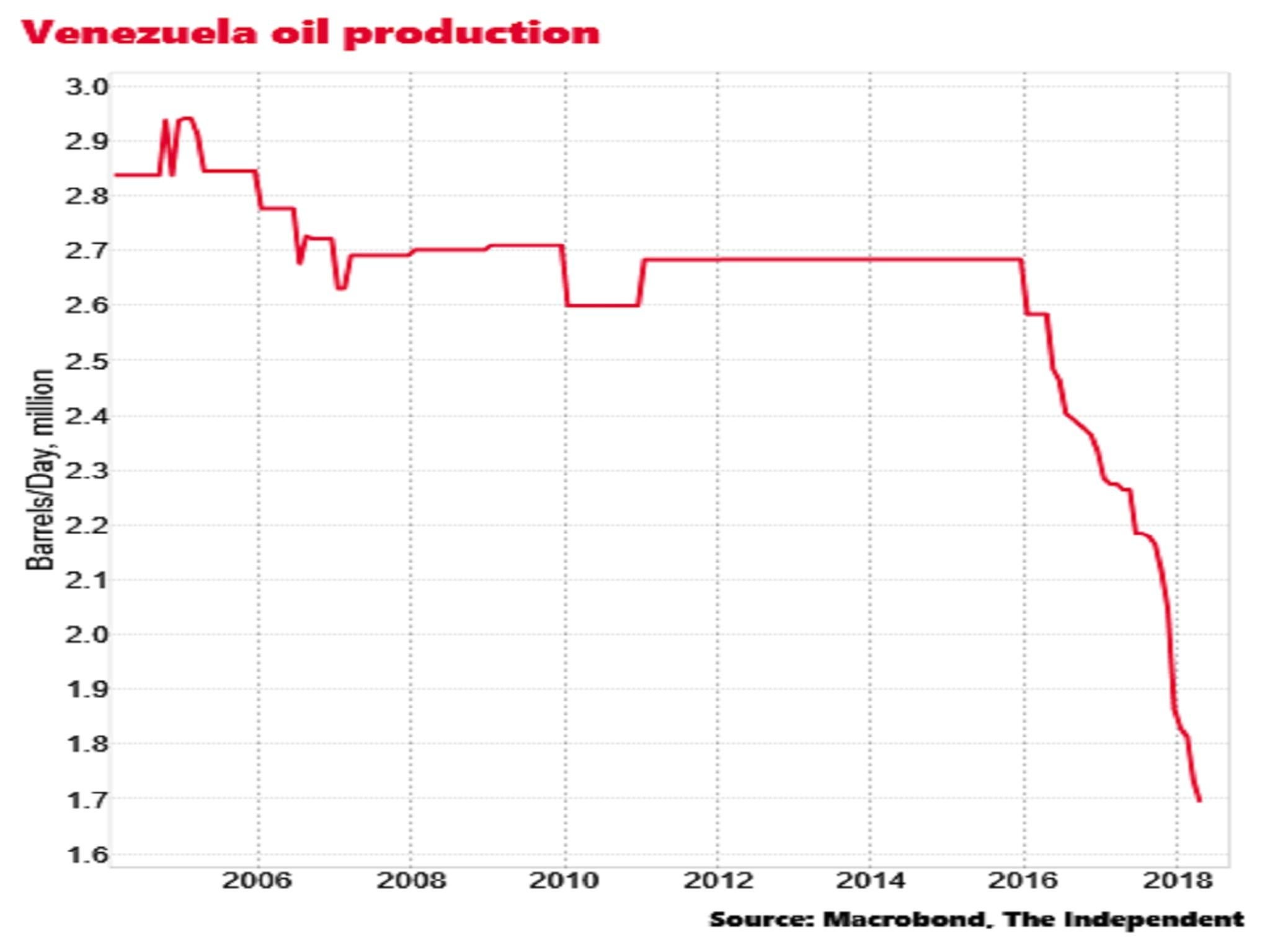

The explosion of prices, combined with a slump in oil production, means that in real terms the country’s economy is expected – by the IMF – to contract by almost a fifth this year, following two previous years of shrinkage.

The Latin American state is in the grip of an humanitarian crisis. Thanks to the dysfunction of the economy and the price system, there are chronic shortages of food and medicine. Three-quarters of Venezuelans have lost an average of 11kg of bodyweight. Doctors report children dying of malnutrition. Malaria cases have spiked due to a collapse in treatment. Emigration has surged. So has crime.

This is what happens when an economy and a society disintegrates.

State foreign exchange reserves, needed for food imports, are draining away. In 2009 they peaked at $43bn (£33.7bn) and they are now down to less than $9bn, raising the prospect of the government and the state oil company defaulting on foreign currency loans, cutting the country off from economic lifelines from the likes of Russia and China.

The Caracas government estimates that it forgoes around $18bn a year due to fuel smuggling, as illicit traders take advantage of the massive discrepancy between the domestic and international price of fuel. Eroding fuel subsidies is a desperate attempt to claw some of that back.

Normally a country in such a state would turn to the IMF for a bailout. But Venezuela broke off relations with the multilateral lender of last resort in 2007, making any rescue very difficult.

How did all this happen? The roots of Venezuela’s agony go deep.

The major modern political rupture in the history of this oil rich country of some 30 million people, came in 1998.

Hugo Chavez, a charismatic former general who had led a coup attempt six years earlier, prevailed in presidential elections by appealing to the poor and the struggling middle classes.

In his early years of power, Chavez and his “Bolivarian Revolution” managed to combine extensive social spending with a degree of economic competence.

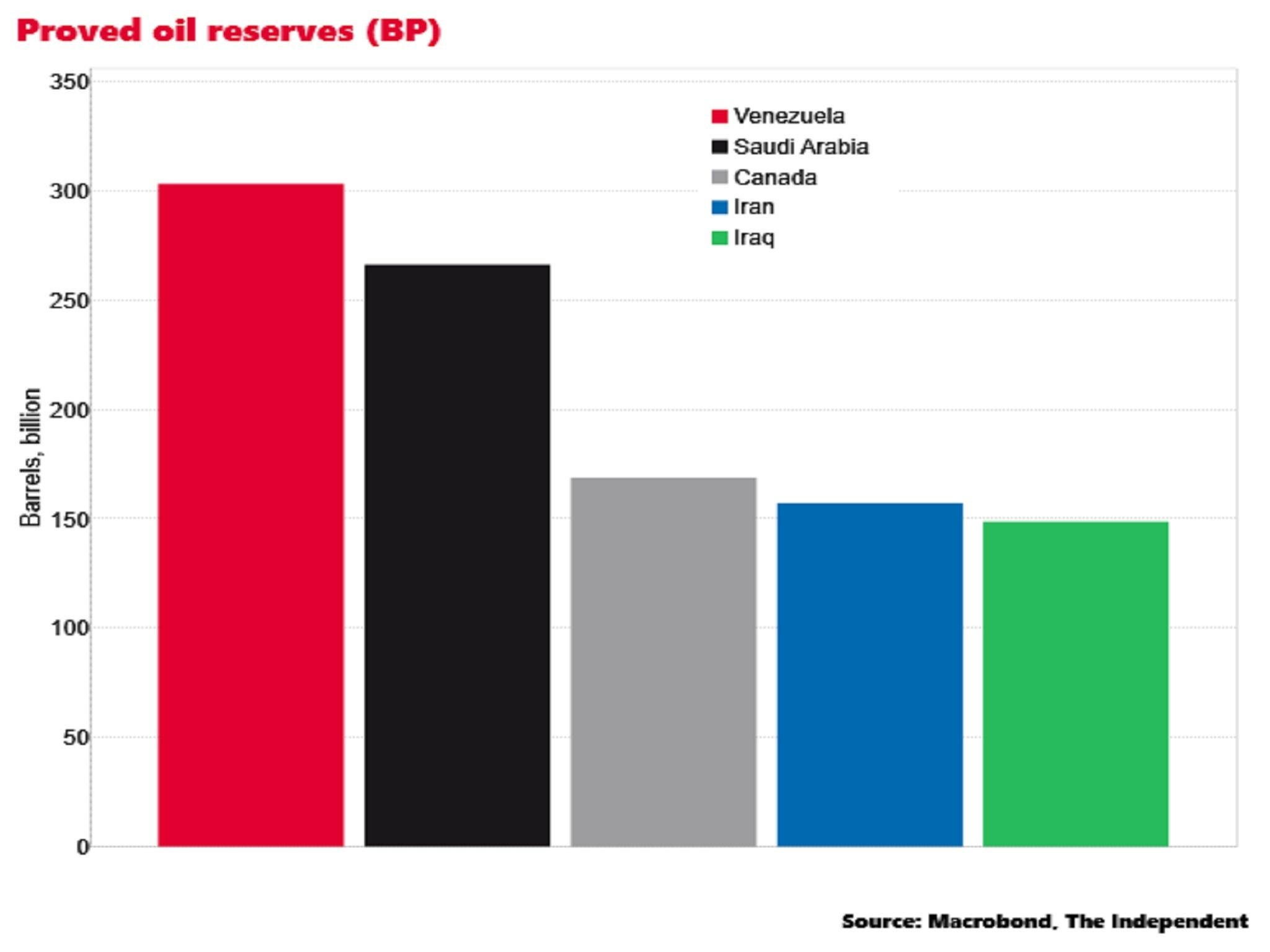

Venezuela has the highest proven oil reserves in the world – some 300 billion barrels. That’s greater even than Saudi Arabia’s.

When the global price was high – between 2005 and 2014 – oil revenues were recycled into welfare programmes and house building for the poor. The results were spectacular. Unemployment and poverty rates halved and infant mortality sank. The performance won praise from socialists around the world, including a certain backbench Labour MP called Jeremy Corbyn.

But Chavez, having long exhibited populist tendencies, started to give them free rein. He became increasingly authoritarian, corrupting the courts and dismantling democratic checks and balances.

Maduro took over when Chavez died of cancer in 2013.

Not long after, global oil prices crashed, wiping out government revenues and sending the state budget deep into deficit. In response, Maduro pressed the accelerator on the country’s journey to economic destruction, ordering the government to simply print money to pay workers, and to continue the distribution of welfare.

Hyperinflation is the result of that monetary incontinence. Government price controls on staples such as flour and cooking oil, combined with collapse of foreign currency for imports, are the cause of the food shortages.

Oil prices have picked up since the middle of last year but the state oil company is crippled by years of underinvestment, meaning it is struggling to raise production. Output has crashed to below 1.69 million barrels per day, down 35 per cent on 2015 levels and less than half the production when Chavez took power in 1999.

Lacking the personal authority, or the economic tailwind of his predecessor, Maduro is plunging the country into ruin.

Thanks to the authoritarian repression and rigged election of this year, Venezuela has become a pariah.

Brazil, Canada and Chile have refused to recognise the Maduro government. Direct US sanctions on Venezuela’s oil exports are a distinct possibility and Donald Trump has even mooted a “military option”.

The only way open for Maduro to stay in power seems to be through more money printing and ever more repression.

Tragically, it seems likely the misery of Venezuelans will deepen before things start to get better.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments