UK households spending more than income for first time in 30 years

The data confirms that British households have been collectively supporting their spending through a combination of reducing their saving levels and taking on more debt

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.UK households collectively spent more than they earned in 2017 – the first time this has happened in almost 30 years, according to the Office for National Statistics.

The data confirms what other indicators have been signalling for some time: that British households have been supporting their spending through a combination of reducing saving levels and taking on more debt, with potentially hazardous consequences for the wider economy.

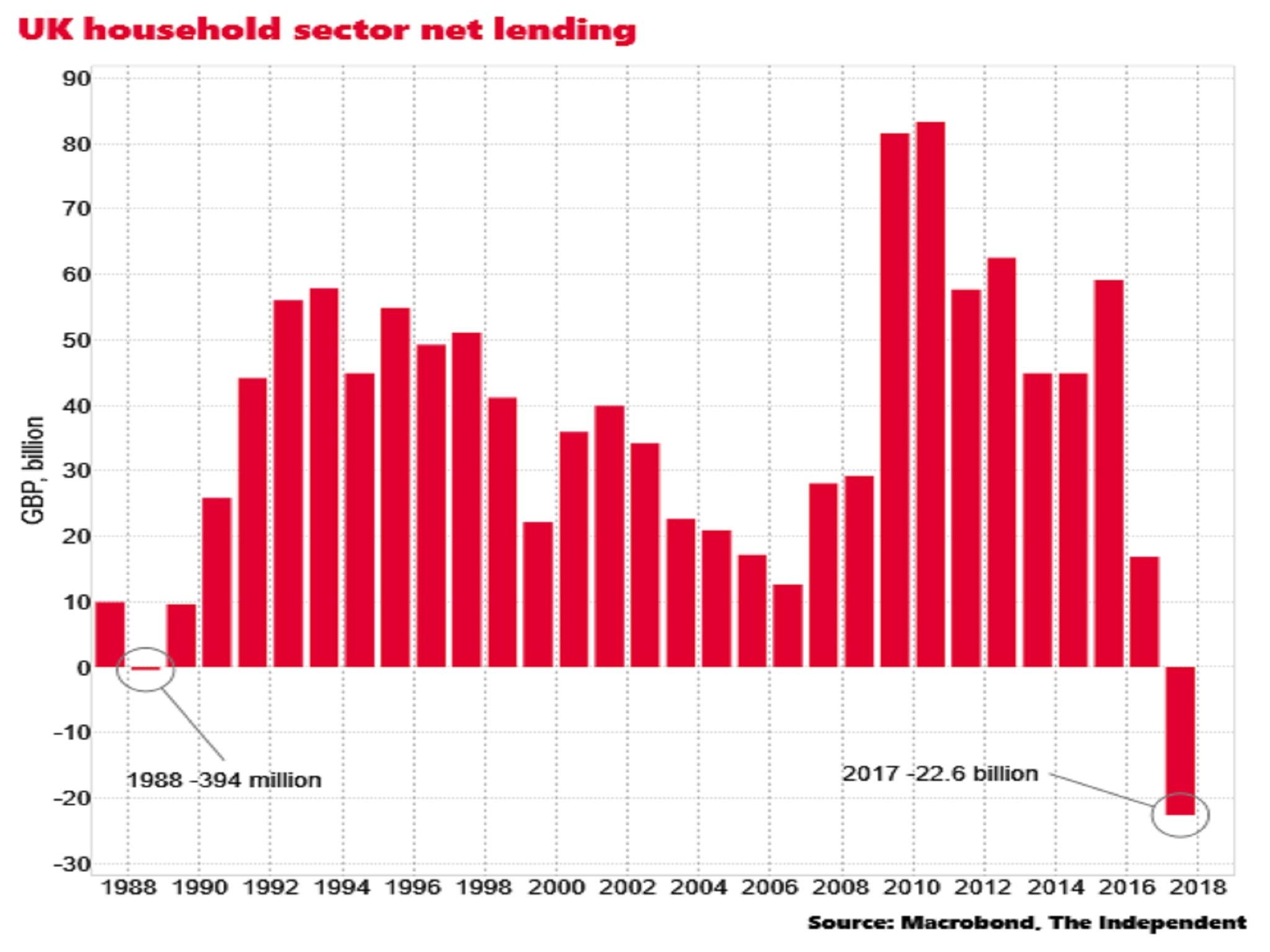

On Thursday the ONS presented figures, taken from last month’s sectoral accounts, showing that the “net lending” of the household sector in 2017 was minus £22.6bn.

The last time this measure was negative was 1988, when there was a deficit of £394m.

Living beyond our means

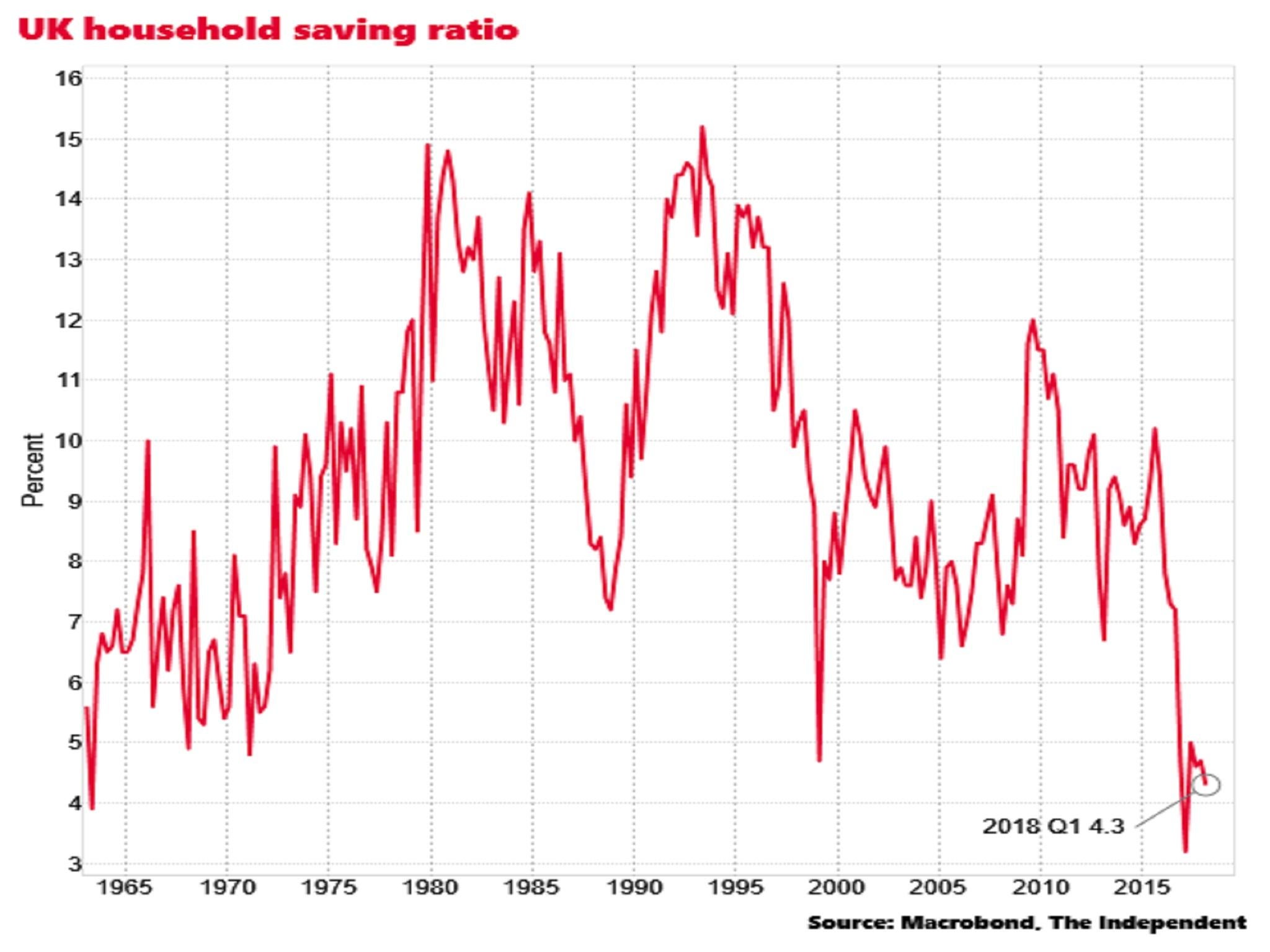

The UK household saving ratio, which measures total saving as a share of total disposable income, dipped to a record low of 3 per cent last year and stood at only 4.3 per cent in the first quarter of 2018.

The difference between the saving ratio and net lending is that that the latter includes households’ investments in home improvement.

Once expenditure, such as the building of loft extensions is included, households, collectively, are spending more than they are taking in after paying tax.

Record low saving

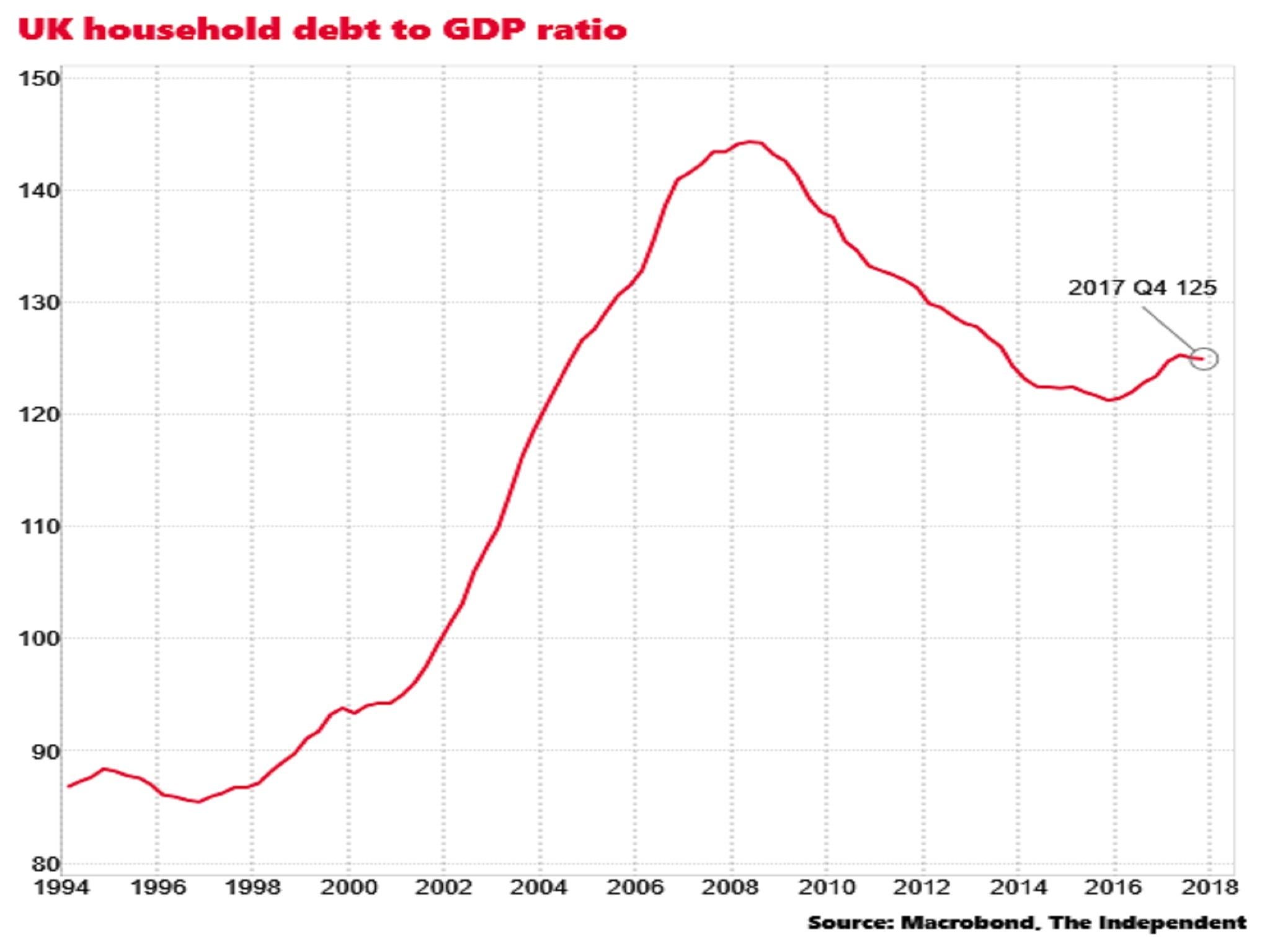

The aggregate UK household debt-to-GDP ratio (excluding student loans) soared in the years preceding the global financial crisis, shooting up from around 95 per cent in 2000 to a peak of 144 per cent in 2008.

This was one of the most rapid household leverage buildups in the world and economists argue that it was one of the reasons Britain suffered such a severe recession a decade ago, as households stopped spending in order to repair their finances, suddenly sucking demand out of the economy.

The debt-to-GDP ratio fell steadily to 121 per cent in 2015, as households steadily reduced their leverage, but it has been creeping up over the past three years and now stands back at 125 per cent.

This debt is mainly made up of mortgage debt, reflecting high and rising UK house prices.

But unsecured consumer credit borrowing – things like car loans and credit cards – has been growing rapidly since 2015, outstripping income growth and prompting warnings to private banks from the Bank of England about their underwriting standards.

Debt rising again

However, the Bank has also noted that the debt-service burdens on households seem manageable by historic standards, reflecting the environment of still very low interest rates.

And it calculates that raising interest rates from 0.5 per cent to around 1.5 per cent in the coming years is unlikely to tank the economy.

Yet, others are less confident about the financial resilience of the household sector.

UK households have largely sustained overall GDP growth over the past decade through their spending, as business investment and exports have been disappointing (despite two major depreciations of the exchange rate).

But this leaves the economy vulnerable – if UK households were to decide that they are uncomfortable increasing their borrowing or running down their savings further.

Last year, Charlie Bean, a member of the Office for Budget Responsibility’s executive committee, suggested that further falls in the saving ratio may not be “sustainable”.

The OBR’s latest forecast in March shows the ratio remaining broadly steady over the next four years, but the household sector’s net lending languishes in negative territory until 2023.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments