The Big Question: Should the Church be entering the controversy over the $700bn bailout?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

Because the two most senior Anglican clergymen in the country have launched a scathing, double-pronged attack on the world's stock market traders, accusing them of being "bank robbers" and "asset-strippers" among other things. Their comments came after a week of global financial turbulence in which four major financial institutions went bust or were taken over and as the US Congress bickered about a multi-billion pound "bailout" to steady the markets.

How have they gone public?

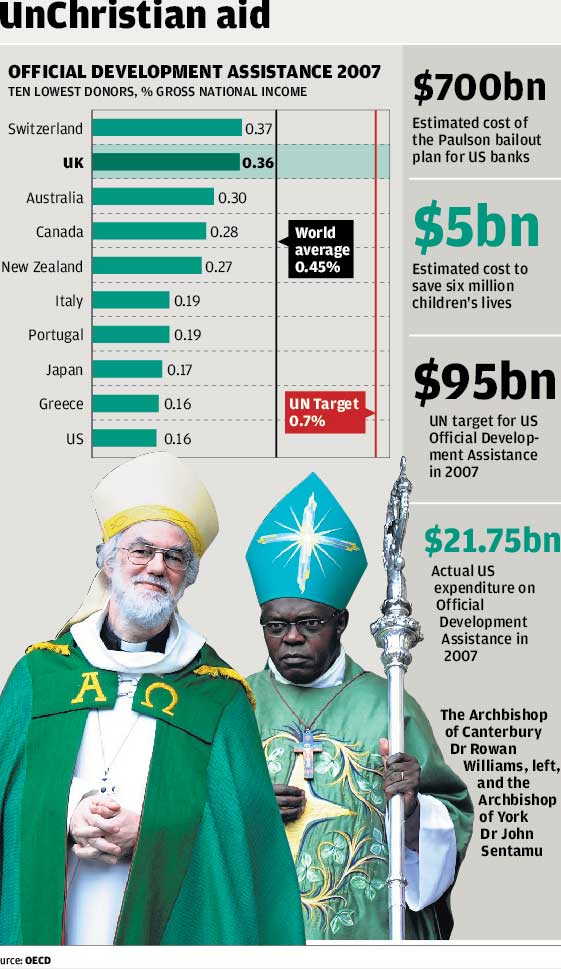

The Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams launched the opening salvo with an article for this week's Spectator magazine defending Karl Marx's attacks on "unbridled capitalism". And on Wednesday evening, during a speech to religiously-minded business folk at the Worshipful Company of International Bankers' annual dinner, Dr John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York, waded into the row by criticising those involved in the practice of short-selling and lambasting rich governments for failing to live up to their aid promises.

What in essence are the Archbishops complaining about?

Money, and how we spend far too much time chasing it. Rowan Williams went for a trademark cerebral article whilst his colleague in York opted for a fiery speech to City leaders but their motives were essentially the same: to chastise us for idolising the god of money. In his article the Archbishop of Canterbury warned that the world's current devotion to the free market is a form of "religious fundamentalism" and suggested that Karl Marx was right in his analysis of the power of "unbridled capitalism". He called for greater regulation of the markets and attacked trading in debt – a process where "almost unimaginable wealth has been generated by equally unimaginable levels of fiction, paper transactions with no concrete outcome beyond profit for traders."

What about Dr Sentamu?

He took to the podium and lambasted a market system "which seems to have taken its rules of trade from Alice in Wonderland." He reserved particular disdain for those involved in the short-selling of HBOS' shares last week which led to Britain's largest mortgage lender being bought by Lloyds TSB after its stock plummeted. "To a bystander like me," he said. "those who made £190m deliberately underselling the shares of HBOS, in spite of a very strong capital base, and drove it into the arms of Lloyds TSB, are clearly bank robbers and asset strippers." The Archbishop of York, who was in New York yesterday at a UN summit on the progress made by world leaders to end poverty, also noted the way the US government was happy to come up with $700bn to buy back bad debt but rarely lived up to its international aid promises.

What about the Church's own investments in the City?

Considering the Church of England has enormous amounts of wealth invested in the stock market the Archbishops' comments certainly risk accusations of "pot calling the kettle black". According to its own website, the Church oversaw assets worth more than £5.67bn at the end of 2007, much of it invested in the stock market, real estate and private equity investments.

The body in charge of managing the investments has also done rather well. The Church Commissioners made a return of 9.4 per cent in 2007, smashing its benchmark of a 7 percent return for comparable funds.

How has the City reacted?

The Archbishops' criticism of short-selling drew an angry response from The Association of Private Client Investment Managers and Stockbrokers, the representative body of the stockbroking industry. In a statement sent yesterday the group's chief executive, David Bennett, said: "It is market abuse which is wrong, and this can occur both when holding either long or short positions. Transparency is the key here." But the two most senior clergy in the country, who oversee a Church of more than 77 million believers worldwide, may have felt compelled to give spiritual advice at a time of global financial crisis. As Dr Sentamu reminded people in his speech: "Money is the root of all evil."

Was Dr Sentamu right to compare the bail-out to poverty aid?

The Archbishop of York was quick to point out the disparity between how quickly western governments act to give a helping hand to the markets during a crisis compared to how reluctant the same governments are when it comes to providing aid.

Referring to the US government's plans to buy back $700bn worth of bad debt from the banks he said: "One of the ironies about this financial crisis is that it makes action on poverty look utterly achievable. It would cost $5bn (£2.7bn) to save six million children's lives. World leaders could find 140 times that amount for the banking system in a week. How can they tell us that action for the poorest is too expensive?"

It's certainly true to say that western governments come up with the cash mighty quickly when the markets are in trouble but the $700bn George Bush wants Congress to release is not the same as aid. It's an investment that the US state hopes to make money out of. The $700bn will be used to buy all the distressed assets currently held by banks in order to kick-start the markets again but the US government hopes it will then be able to sell these assets back with a profit once the market is in a better shape.

So how far has the world progressed on its aid promises?

The Millennium Development Goals, set by world leaders in 2000 to drastically reduce global poverty by 2015, are largely being met in Asia but little progress has been made in Africa. Earlier this week UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon warned that Africa alone needed $72bn a year in aid – a "daunting" sum but one, he pointed out, that was a tenth of the US bail-out and much less than the estimated $267bn spent last year by the world's industrialised countries on agricultural subsidies. According to the World Bank, aid from traditional donors fell by over eight per cent in 2006-2007. The crisis has been compounded by the huge rise over the past year in food and oil prices.

What difference would $700bn make if applied to poverty?

It wouldn't eradicate global poverty overnight but it would be an unprecedented amount of aid at a time when financial help is needed more than ever; $700bn would be a simply astonishing amount of aid – the equivalent to seven years of international aid in one go. Last year $103.7bn was given in overseas development aid from the top 22 donor countries, a figure dwarfed by the US bailout. The G8, meanwhile, is struggling to stick to its promise to increase aid by $50bn by 2010. But such a huge injection of aid at once could be damaging. Unless carefully regulated, much of it would disappear into the pockets of corrupt leaders and businesses that have long profited from the global aid industry. Then again if every cent went to those who actually needed it, $700bn would be the closest thing to a poverty-busting silver bullet.

Should the rescue plan $700bn go to the poor instead?

Yes...

* Millions die needlessly every year from poverty and the Western world is failing to meet its own aid targets.

* Recent increases in the price of oil and food have left the world's poor more vulnerable that ever.

* The stock markets should be taught that they cannot simply rely on handouts when they get it wrong.

No...

* That $700bn is desperately needed to steady the chaotically turbulent financial markets.

* Releasing so much in one go would flood the world with aid: much would be taken by corrupt governments.

* The US bailout isn't even comparable to aid. It's an investment from which the state will ultimately profit.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments