The Big Question: Does BP's discovery of a giant new field prove we're not running out of oil?

Why are we asking this now?

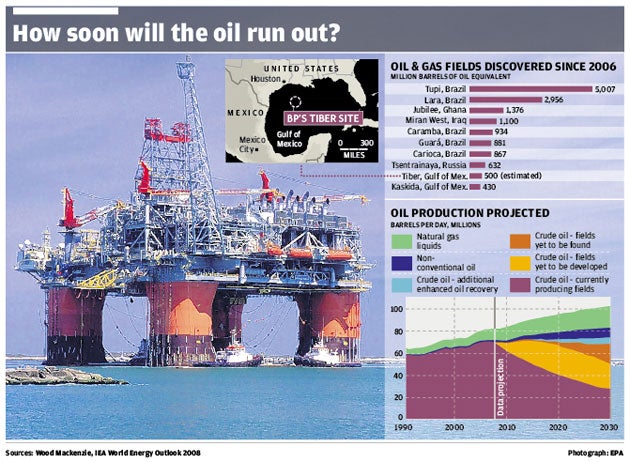

On Wednesday, BP, the UK energy group, announced the discovery of a "giant oilfield" in the Gulf of Mexico that could open up a huge new frontier in oil exploration. It comes less than a week after Iran announced an even larger discovery of crude oil, and is the latest in a spate of finds over the past few years. Taken together, the discoveries have emboldened sceptics of the notion that oil will soon run out, and reignited the debate on an issue with huge implications for the environment, and geopolitics more broadly.

How big is this discovery?

Named the Tiber, the new field lies in US territorial waters and is one of the biggest finds this decade. It is thought to hold at least 3 billion barrels of oil (and possibly more), only 500 million of which are recoverable with present technology. The field was found by the deepest oil well ever drilled, reaching 9.4km (almost six miles) below the sea bed, and sits below 1,200m of water some 250 miles south-east of Houston, Texas.

BP has been pioneering the exploration of the Lower Tertiary or Paleogene area of the Gulf of Mexico, which is deeper than the strata of the earth that provides most of the region's known reserves. Lower Tertiary rock was laid down between 34 million and 66 million years ago.

Is this really 'a Forties field or even bigger'?

So gushed an excitable spokesman for BP on Wednesday. Shortly after, he added: "Appraisal will be required to determine the size and commerciality of the discovery." Forties was the biggest field on the UK side of the North Sea. It is estimated to have had reserves of between four and five billion barrels and, at its peak, in the mid-Eighties, was delivering half a million barrels a day. We simply don't yet know how much oil there is in Tiber, so comparisons are largely devoid of meaning.

Andy Inglis, chief executive of BP exploration and discovery, said: "Tiber represents BP's second material discovery in the emerging Lower Tertiary play in the Gulf of Mexico, following our earlier Kaskida discovery." The Kaskida field was found in 2006. It is estimated to contain three billion barrels, though it is still being evaluated.

What about Iran's recent discovery?

Gholam Hossein Nozari, Iran's oil minister, announced last week that an estimated 8.8 billion barrels worth of crude oil had been found in four new layers at the Sousangerd oilfield in the south eastern Khouzestan province. Explorers had drilled to a depth of 5,026m. Iran sits on the world's second largest oil and gas reserves.

What does this mean for BP?

Elation greeted the latest discovery – and not just in BP's headquarters in London. BP owns 62 per cent of Tiber, with Petrobras, the Brazilian state-owned explorer, owning 20 per cent and ConocoPhillips 18 per cent. Investors were sufficiently convinced by the "Giant Oil Discovery" headlines to add £4bn to the value of BP on Wednesday alone. Even by the standards of the oil industry, that is extraordinary. It pushes the company's wealth over the £100bn mark, and is the biggest discovery yet under the two-year stewardship of chief executive Tony Hayward, for whom this is something of a personal triumph.

It should help BP maintain its impressive record of adding more new reserves each year than it depletes in production – something it has boasted of for 15 years. The discovery is also an endorsement of BP's big bet on the Gulf of Mexico, where it has invested heavily.

The find is in the US-controlled sea-bed. The site is particularly attractive to drilling companies not only because of the promise of oil, but because they have to pay the US less in taxes, royalties, and other drilling-related levies than most governments demand.

So does this disprove the Peak Oil theory?

Strictly speaking, "peak oil" is a fact rather than a theory, as nobody sane doubts there is a finite amount of oil on the planet. Once this is granted, the contentious issue is not the fact of peak oil, but the imminence of it. How soon will we run out? The discoveries made over the past decade – and there have been several of them – seem to confound doom-mongers. It is not just established areas like the Gulf of Mexico and Iran that seem to be soaking in the black stuff; new areas such as Greenland, Uganda, and the northern coast of Ghana are also proving flush.

"It's an amazing turnaround from the gloom of the last 10 years," said Peter Odell, professor emeritus of international energy studies at Erasmus University in Rotterdam. "All these finds will take a long time to bring on-stream, but it shows the industry is capable of finding more oil than it uses and shows we have not come to any peak."

Surely we can't overcome supply and demand?

So say the more radical proponents of "peak oil". With a growing world population, and with the world's poor consuming more energy (a welcome sign of their better welfare), at some point growing demand is going to run up against shrinking supply. It is inevitable.

Jeremy Leggett, an influential peak energy theorist who works for renewable energy firm Solarcentury, points out a stark recent warning: "The International Energy Agency said in its 2008 report that the world needed to find six new Saudi Arabias to meet the growing demand for oil in the future." Given this, the imperative to build effective, long-lasting supplies of renewable energy is only going to get bigger, despite recent discoveries.

Can we expect more big discoveries?

It is worth bearing in mind not only that giant fields are the lifeblood of the industry, but that the overall rate of discovery is on a downward trend. The 20 largest oil fields – out of around 70,000 around the world – account for a quarter of all production; the largest, Ghawar, discovered in Saudi Arabia in 1948, is only halfway through its 140 billion barrels. But while in the Sixties around 56 billion barrels were being discovered each year, that fell to 13 billion in the Nineties. And most new discoveries are off-shore and under deep waters (where they are much more expensive to extract).

For those worried about recent shocks in the price of oil, and the global economy's extreme over-reliance on oil, the new discoveries are welcome relief. But they cannot disguise the fact that supply is generally declining as demand is generally growing. Their effect is only to delay the inevitable.

Where does this leave global reserves of oil?

We simply do not know how much oil is left on the planet. What we do know is that the ratio of reserves to production has remained relatively constant for many years.

This isn't because of new discoveries; rather it is because as prices rise it becomes easier to extract more oil from existing fields; as companies drill, they realise there is more there than they thought. So yields in-crease. Raising recovery rates from 35 per cent to 50 per cent would double world reserves to more than 2,400 billion barrels.

Do recent discoveries prove that we won't run out of oil any time soon?

Yes...

* The sheer scale of recent discoveries suggests that we may have underestimated how much oil we have.

* It's not just the scale, it's their location: new fields in Africa and beyond provide plenty of hope.

* Better yields on present fields boost reserves; new production techniques will help push this further.

No...

* The insurmountable difficulty with oil is that there is a finite supply but growing demands.

* Despite a plethora of recently found fields, overall new discoveries have been declining for decades.

* Most new finds are off-shore and under deep water, meaning it is difficult and expensive to extract.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments