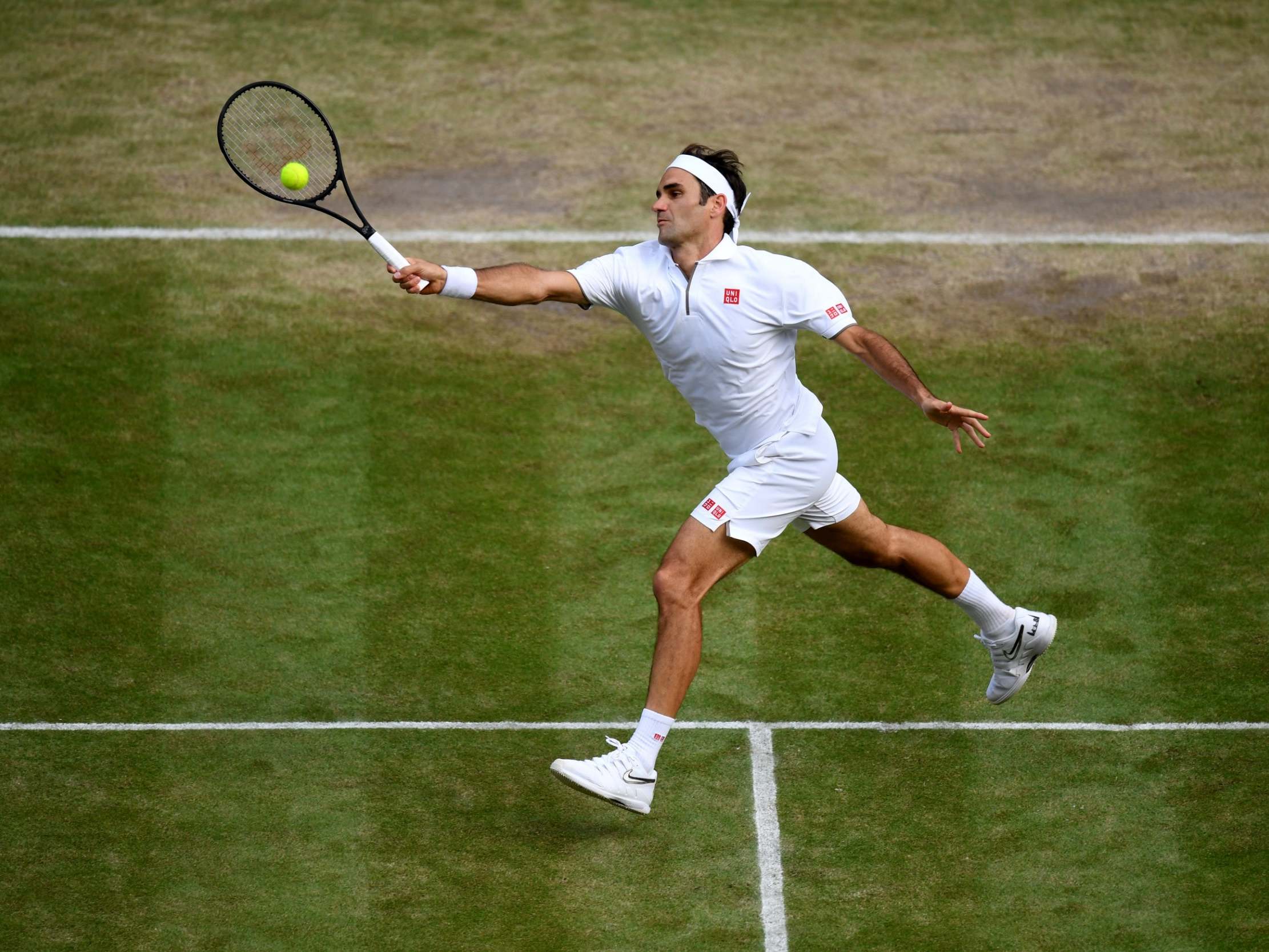

Why businesses should take a lesson from Roger Federer on media strategy

Johanna Konta’s outburst after crashing out of Wimbledon provides a timely reminder of the benefits to be gained from a calm approach to journalists

The most popular sportsperson on the planet by far, surely, is Roger Federer. There are famous footballers and basketball players, and cricketers, but their fan bases are tribal. Federer enjoys universal appeal. It’s not just the gracefulness and artistry of his tennis, though, that puts him ahead of anyone else. He always seems to conduct himself in a polite, understated, considerate manner. The same skilful gliding and disarming he brings to the tennis court, Federer takes into the press conference. He once said that he never saw the media as his enemy.

The comparison has already been made with the up and coming British player Johanna Konta. When she lost at this year’s Wimbledon, due to a series of unforced errors, she rounded on the journalist who pointed out her weakness. The clip of Konta snapping back has been played repeatedly: “Please don’t patronise me. In the way you’re asking your question, you’re being quite disrespectful and you’re patronising me. I’m a professional competitor who did her best today, and that’s all there is to that.”

It’s tough when you’ve just been defeated in a match you were expected to win – one that had you triumphed would have taken you to the semi-final of a Grand Slam – and you’re required to face a battery of cameras and questions. Nevertheless, it comes with the job.

Federer, for one, handles such episodes with nothing but good grace. Of course, he’s frequently sitting there as the victor. But he’s had his defeats as well. It’s likely that Federer would agree with the interrogator: yes, he made mistakes; yes, he’s disappointed; yes, he’s going to work on what caused them. That’s all Konta needed to say, but instead, she went hostile. It was not a good look, for her, for her sponsors. Before she loses again, she must be taught how to charm, even in the most strained of circumstances. Konta should study Roger (another sign of the affection in which he is held is that mention of the first name will suffice, everyone knows who is being referred to).

It’s not only Konta who could do with copying Federer. There’s a vital lesson here for business, too. By and large, those companies, those business leaders, that enjoy a good press, also treat the media as a friend. They’re available and willing, helpful and informative as much as they’re allowed. Those that are the constant subject of criticism tend to be those that occupy an obdurate, negative stance.

The difference is often the reason why some businesses and their bosses are able to ride out a crisis, while for others it’s part of a downward spiral. No one comes to the latter’s rescue, nobody has a good word. Worse, there’s an element of willing them to fail, of the media relishing their difficulty. Look at what happened to Fred Goodwin at the Royal Bank of Scotland. No sooner did his organisation hit trouble than the press piled in, targeting the bank’s chief executive. There was a definite sense of revenge, as they hammered Goodwin, who in his pomp had been prickly and carping in his dealings with journalists.

Likewise, moving more up to date, the likes of Mike Ashley and Michael O’Leary. Neither Ashley at Sports Direct and Newcastle United, nor O’Leary at Ryanair, enjoy glowing press coverage. Why? Because both men do not embrace the media.

Of course, they attract opprobrium for the funding of Newcastle United, say, in Ashley’s case, or the handling of customer complaints by Ryanair in O’Leary’s. But the fact they make little effort to explain, to show a friendlier side to journalists, only hardens their images.

It’s not easy when you see yourself being attacked. The natural tendency is to suspect the journalist is pursuing a vendetta

There are those who struggle with the notion of following the Federer example, and believe me, regardless of how much they try to be warm, the press will always be their enemy. They’re often those who maintain that what is written or broadcast about them is personal, that the journalist concerned is motivated by some ulterior motive or hidden agenda.

It’s not easy when you see yourself being attacked in public. The natural tendency is to suspect the journalist is pursuing a vendetta. Usually, though, this is not the case. All they are doing is reporting what others have said, they’re only the messenger. Instead of hounding the hack, a wiser strategy might be to study the message and to work out a considered response.

Media outlets in my experience will clamp down heavily on any journalist they suspect of settling scores. They know that can be a recipe for disaster, for an inaccurate, unbalanced report that could lead to ridicule and a libel suit. It’s simply bad journalism. Even without the lead of Roger, I usually tell clients to learn to treat the media as a friend. Be courteous, be accessible, be patient. Don’t be snide and sarcastic. Definitely don’t be rude.

Remember Jeff Fairburn. He was the UK’s highest-paid chief executive, at housebuilder Persimmon. Then, he refused to answer on live TV a reporter’s questions about his £75m bonus. Fairburn told the BBC journalist, it was “really unfortunate that you’ve done that [asked about his remuneration]”, before walking out of shot. Within weeks, Fairburn lost his job.

Chris Blackhurst is a former editor of The Independent, and director of C|T|F Partners, the campaigns, reputational, crisis, and strategic communications advisory firm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments