What is productivity? And why does it matter that it is falling again?

What does this mean for ordinary people? Why should it concern us? And what can we do about it?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The UK’s productivity has fallen again, the Office for National Statistics reported on Friday.

But what does this mean for ordinary people? Why should it concern us? And what can we do about it?

What is productivity?

It refers to the amount of work produced either per worker or per hour worked.

So if a baker produced ten loaves of bread in an hour work, his personal bread-making productivity would be 10 loaves per hour.

In the context of the entire economy productivity refers to the amount of GDP (the value of all goods and services) output in a period of time divided by all the hours worked by all the workers in the economy over that same time period.

So what’s been happening to it?

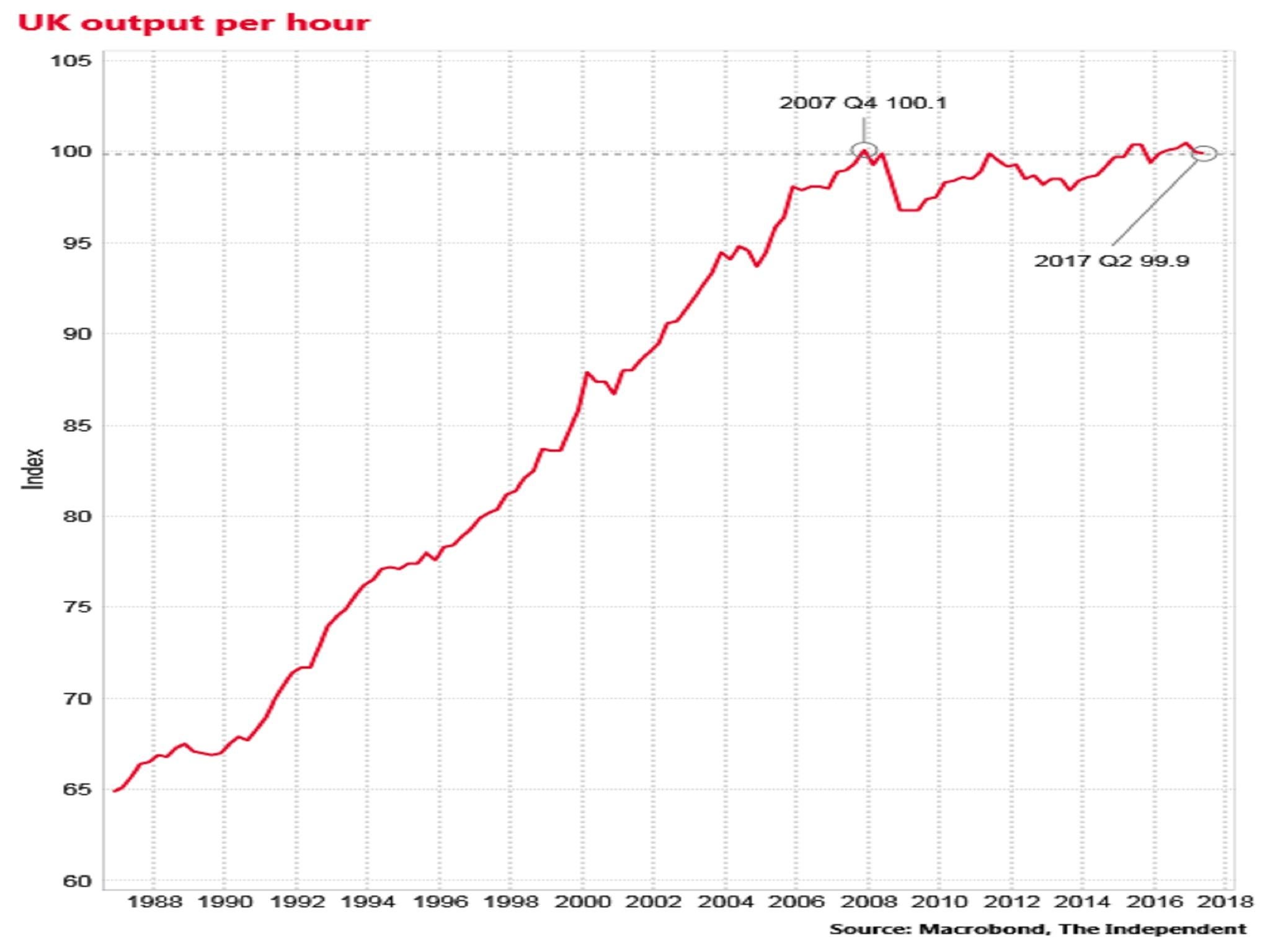

Since the end of the Second World War until 2007 productivity grew at an annual rate of around 2 per cent a year.

But since 2008 it has flatlined. The UK’s level of productivity today is no higher than it was in the final quarter of 2007, which is an astonishing and unprecedented period of weakness.

And in the second quarter of 2017 productivity actually fell again, declining by 0.1 per cent.

Why does it matter?

Productivity growth reflects the degree with which we are all producing economic output more efficiently.

If productivity is rising we can pay workers more for their efforts without risking an inflationary spiral.

If it is flat that means it’s difficult to raise wages. There is a direct connection between flat productivity since the crash and the fact that average wages in the UK are still lower than they were a decade ago.

Productivity also matters for the public finances. Rising productivity tends to translate into more tax revenues to pay for the public services we consume.

The Treasury’s official watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, is preparing to downgrade its estimate of the UK’s future productivity growth.

This will likely open up a hole in the future public finances, which may need ultimately to be closed by cutting services further or raising taxes.

How can we raise our productivity?

With difficulty, not least because the reasons for its stagnation since 2007 are still something of a mystery for economists.

Economic theory and empirical evidence suggests investments in technology, infrastructure, research and education are the primary ways of raising productivity. Immigration and trade also seem to help.

Part of the problem in the UK seems to be that some companies are chronically failing to adopt the better management and organisational techniques of other more successful firms in their same sector, so rectifying this transmission of expertise failure could also be very beneficial.

But no one has a magic bullet. One thing that most economists agree on is that leaving the European Union is unlikely to help lift the UK’s productivity growth rate, and indeed is more likely to retard it, since Brexit threatens to cut trade, restrict immigration and curb business investment.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments