Long-term NHS plan: Does the UK health service provide value for money?

Just how does the NHS compare to other health systems when it comes to value for money? Should we be learning from abroad?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The government produced a “long-term plan” for the National Health Service on Monday.

This is designed to outline how the £20bn a year funding boost by 2023-24, announced last year, will be spent.

Labour, unions and various health group say the plan is underfunded and will not fill widening staffing gaps.

The Institute of Economic Affairs, on the other hand, complains that the plan does not allow for greater “competition” or “patient choice” and argues that ministers have refused to heed the lessons from superior and more efficient European health insurance systems.

So just how does the NHS compare to other countries’ health systems when it comes to value for money? Should we be learning from abroad?

How much do we spend compared to others?

According to the 2018 Budget the UK government will spend £166bn on health in 2019-20. That’s around 7.5 per cent of GDP.

Making comparisons with spending with other countries is difficult due to inconsistencies about what is recognised as health spending. Should spending on hospital IT systems, for instance, count?

Another complication is that in some countries a substantial share of health spending comes from social or private insurance.

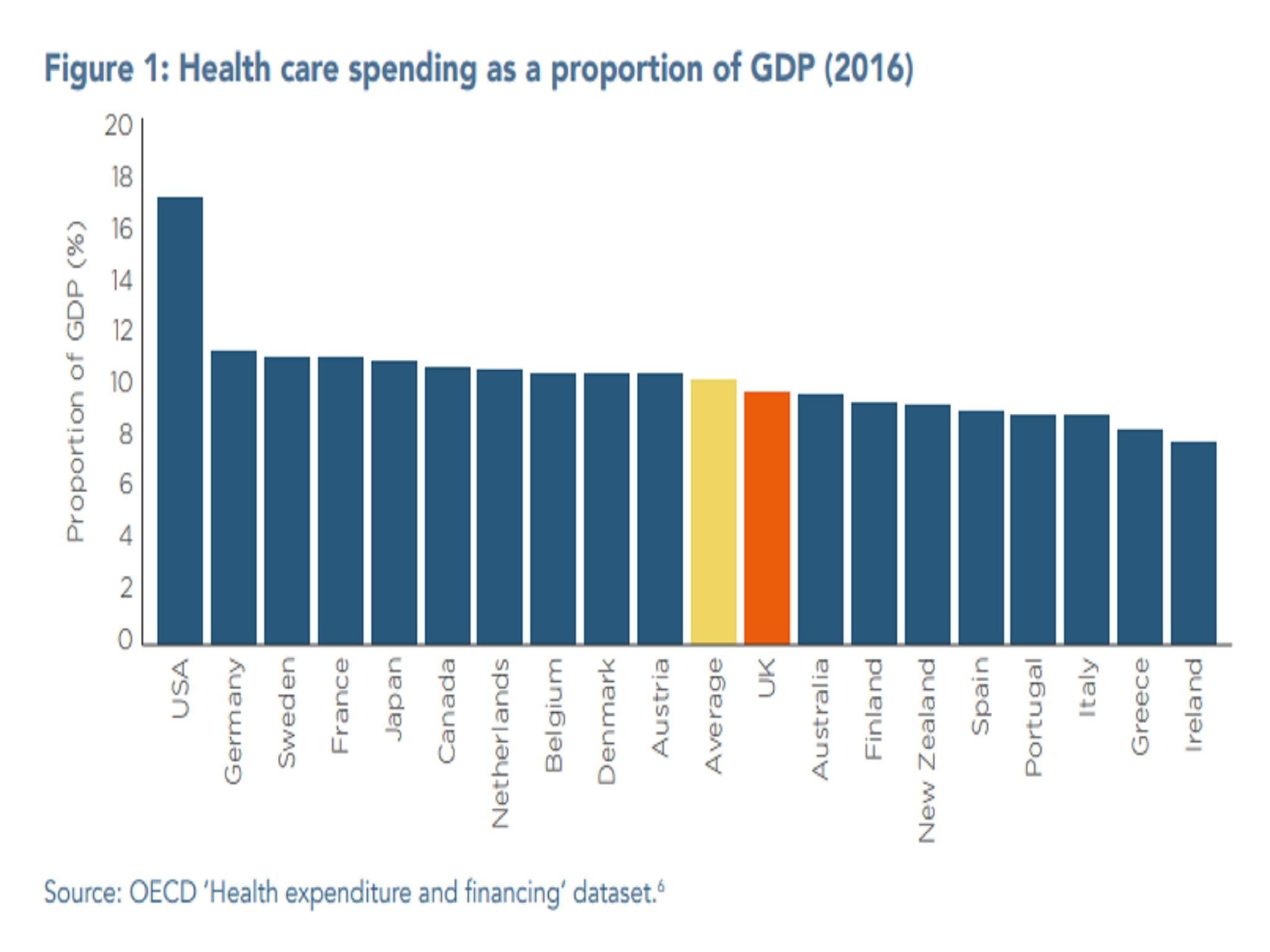

But the OECD has attempted to produce comparable figures. And this suggests that in recent years the UK’s total spend has been slightly below the average of other rich countries, and quite a bit below the likes of Sweden, Japan, France, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands.

And we spend far less than the US, which is a significant outlier, with total spending on health of 17 per cent of GDP.

Another relevant piece of context when it comes to spending is that, since 2010, the NHS has endured the most severe squeeze in annual funding growth since its foundation in 1948, with real-terms spending up by 1.4 per cent a year on average, compared with 6 per cent a year in the previous 15 years.

What are the UK health outcomes compared to other countries?

Disappointing.

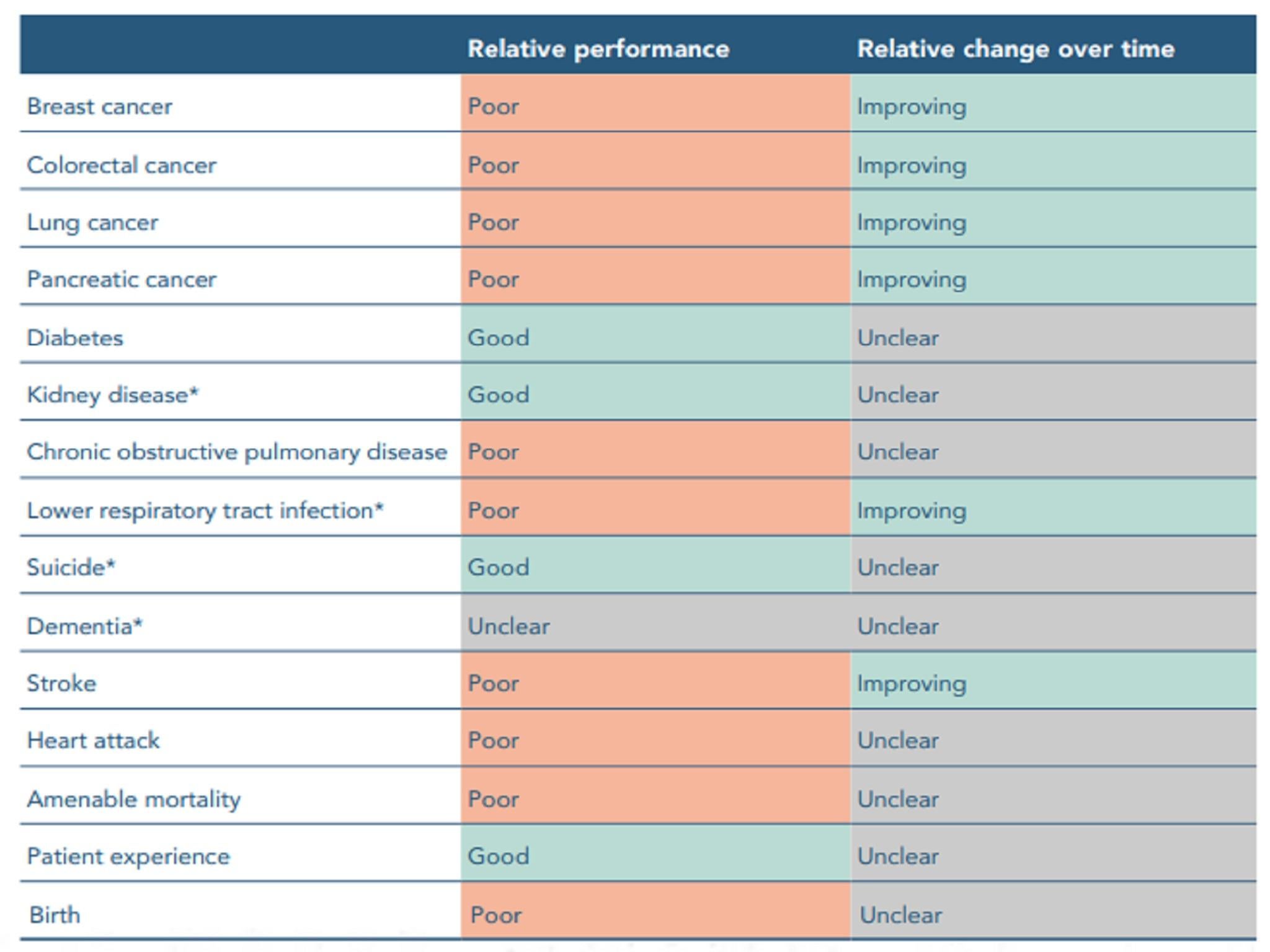

Mortality rates for several forms of cancer, stroke and heart attack are worse in the UK than comparable countries. Child mortality around birth is also relatively elevated.

“The reality is that the NHS is not doing as well as its counterparts at saving the lives of patients with many of the most common and lethal illnesses,” concluded a report by the Health Foundation, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the Nuffield Trust and the King’s Fund last year to mark the NHS’s 70th birthday.

So is there waste in the NHS?

Almost certainly. Any £166bn budget will have a large number of places where more is being spent than strictly necessary.

A review by Lord Carter in 2016 identified £5bn of possible savings in acute hospitals in England. This included savings from better staff rostering practices to sourcing medical supplies more cheaply.

Yet other systems will have similar efficiencies.

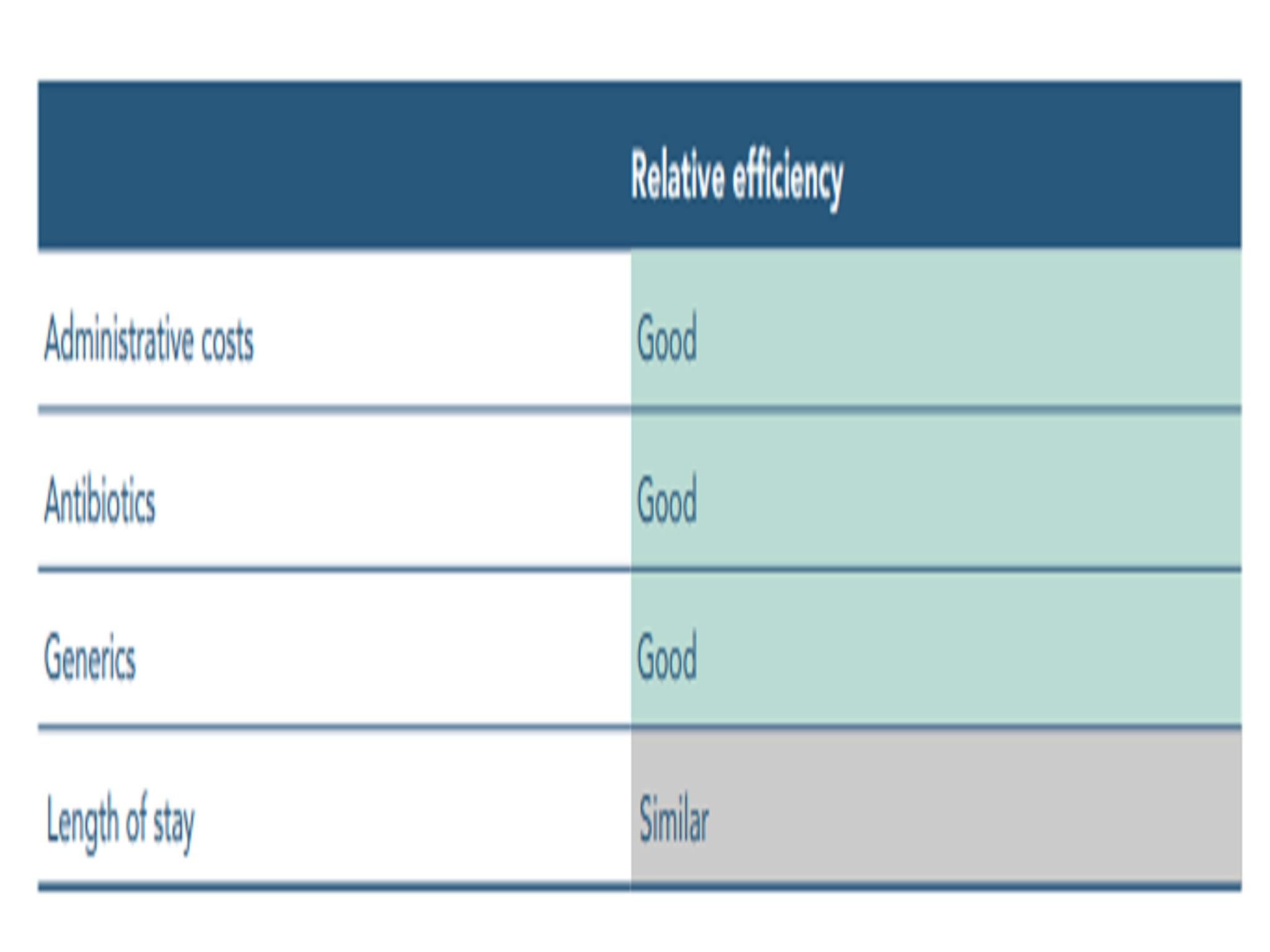

And the OECD research has found that the NHS spends relatively little on overseeing and planning care, relative to other comparable systems.

In 2014, the UK spent 1.5 per cent of its healthcare budget on administration. The OECD average was 3.1 per cent, with 4.1 per cent in France, and 7.9 per cent in the US.

On drug prescribing the UK also seems relatively efficient. We have the largest share of cheaper generic-product prescribing of all our comparator countries, at 84 per cent in 2015 compared with an average of 50 per cent.

The Health Foundation et al report last year concluded that the NHS was “good” relative to peer systems on administrative costs and on antibiotics and generic drug prescribing.

In terms of the length of stay of in-patients the performance was “similar”.

Should the NHS learn from abroad?

The NHS is far from perfect. There are undoubtedly practical lessons to be learned, from how to manage staff better, to curbing drugs bill inflation, to improving diagnosis and treatment, to preventive medicine.

The question of whether more private provision and moving towards an insurance funding model would drive better health outcomes is a moot one.

Simple underfunding in recent years, at a time when the demands on the system have grown, has arguably been a bigger hindrance than these kind of structural or incentive factors.

If the goal of reform is saving taxpayers’ money the solution is unlikely to be found abroad given that relative expenditure levels in comparable countries are mostly higher.

One thing that we can safely conclude is that those claiming the UK can both have a much better service and also pay less for it are selling political snake oil.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments