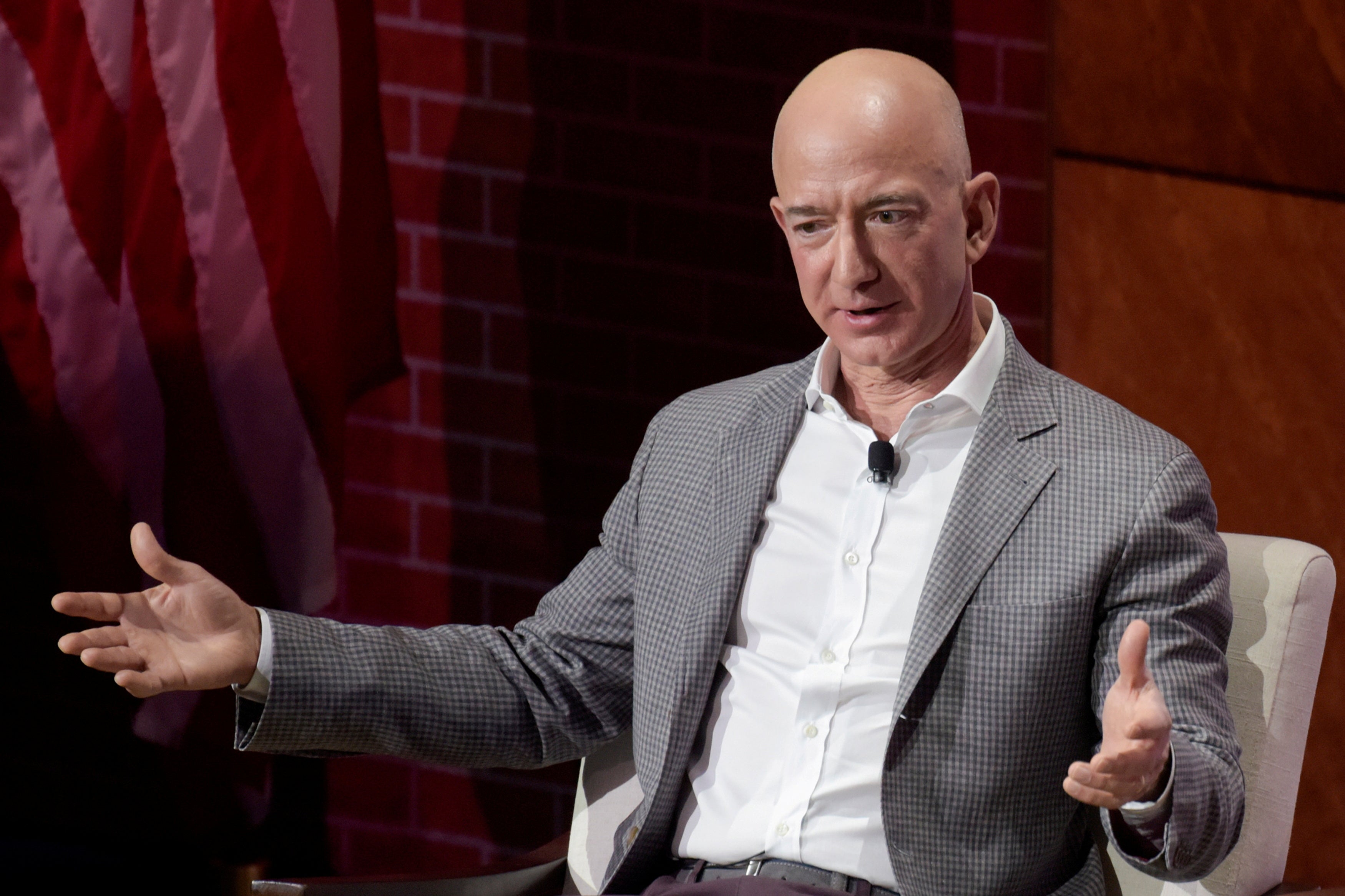

Mapping the Amazon: What is Jeff Bezos’ economic legacy?

The economic footprint left by the Amazon founder is far bigger than just building a vast company and making money for shareholders, as Ben Chu reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jeff Bezos is stepping down as chief executive of Amazon this year, the company he founded in 1994.

He will become executive chairman, but Mr Bezos has stressed that he intends to spend more time with his other projects such as his space exploration company and his climate change fund.

Over the past 25 years the online retailer has grown into one of the biggest and most profitable companies in the world, with a market value of $1.7 trillion.

Someone who bought $100 of Amazon shares on 15 May 1997, when Amazon floated on the stock market, would have seen their investment grow to be worth around $172,000 (£126,000) today.

But the economic legacy of the company that Mr Bezos has built is far wider than growing a huge company and generating wealth for shareholders (not least himself – Mr Bezos’ 14 per cent stake in the company is worth some $200bn (£146.6bn), making him the world’s wealthiest person).

The company is intimately associated with controversies about the treatment of workers, multinational tax avoidance, monopoly power in the digital era and fundamental debates about the shape of the 21st century economy.

Here are some of the main economic legacies of the company that Mr Bezos built.

A war with workers

For many years Amazon has been under intense fire from workers, unions and politicians for paying poor wages to its lower-skilled employees around the world.

In the US Amazon has paid a minimum wage of $15 an hour since 2018, which is double the federal minimum. It pays UK workers a minimum of £9.50 per hour, above the £8.72 statutory floor.

Yet some 4,000 of Amazon’s full-time warehouse employees in the US rely on food stamps, according to data from US Government Accountability Office released late last year and analysed by Bloomberg.

And only this week the US Federal Trade Commission required Amazon to pay out $62m (£45.4m) to some of its delivery drivers to settle allegations that it had pocketed tips for them left by their customers.

There have also been many protests about conditions in the warehouses, including about safety during the pandemic.

The company’s worker monitoring practices have also been criticised as both alienating and sinister.

Although some of Amazon’s European workforce have been able to organise, none of its US workers have successfully, so far, formed or joined a union.

It is currently lobbying hard to discourage warehouse workers in Alabama from unionising.

The company has said in the past that its opposition to unionisation is based on preserving Amazon’s internal culture of “innovation, flexibility and open lines of direct communication between managers and associates”.

To critics Amazon’s opposition is based on (justified) fears that trade unions would push up wages and curb management’s excessive control, increasing the firms’ costs and cutting into its competitive advantage.

Amazon’s fraught relations with its workers has fed into broader concerns about the apparently declining share of all national income flowing to workers (rather than to company owners) in many rich countries in recent decades - and whether this shows that capitalism is failing to deliver for the working classes.

Multinational tax avoidance

Vying with mistreatment of workers in the most frequent criticism of Amazon, is the charge of corporation tax avoidance.

Amazon stands accused of opportunistically and artificially shifting the location of its profits between countries in order to minimise its corporate tax bill, leaving more cash available to the company for investment and expansion.

Research by the Fair Tax Mark group in 2019 pointed to Amazon as the worst of the big six US tech firms in terms of avoiding the corporate income tax.

It estimated that the firm had paid just $3.4bn (£2.49bn) in corporation tax over a decade, working out at rate of just 12.7 per cent of profits over that period. The average corporation tax rate in OECD countries was around double that.

The argument is that this corporate tax avoidance is not only wrong in itself because it deprives countries in which Amazon operates of tax revenues to fund public services, but that it also distorts domestic competition.

Research by the Centre for Economics and Business Research in 2017 suggested traditional UK booksellers were collectively paying 11 times as much corporation tax to HMRC as Amazon.

This behaviour from Amazon and others has forced national governments to try to cooperate to prevent multinationals picking and choosing where to pay tax - and sparked much debate on the social responsibilities of footloose multinationals.

Monopoly power

Amazon claims it has “empowered” many small firms, by enabling them to sell online, and there’s a considerable element of truth in this. The rise of e-commerce, with Amazon at its head, has allowed all sellers to reach buyers much more easily.

Yet the more retailers sell through Amazon, the more dominant it grows as a platform.

And Mr Bezos has used Amazon’s leading position in the e-commerce market to extend deep into a host of other areas, from cloud computing, to voice recognition devices like Alexa, to entertainment and sports broadcasting and even opening physical shops.

That all re-enforces the dominance of the firm in a virtuous (for the company) circle. Its access to vast amounts of customer data also gives it a considerable advantage when it comes to targeting products at customers, cross-selling and general commercial expansion.

As a result, the company is now facing investigations from both US and European regulators over that monopoly position.

A debate is intensifying over the sheer power of giant technology firms and whether such power is compatible with a functioning democracy.

The 21st century economy

Amazon has undoubtedly created a great deal of value to consumers all around the world.

And it is the service of the moment. Lockdown would be much harder to bear for many without regular and speedy parcel deliveries by Amazon.

Yet the adverse economic and social consequences of Amazon’s domination are also increasingly obvious in the form of the hollowing out of many high streets, with smaller bricks-and-mortar rivals unable to compete with the ubiquitous online retailer.

Relative to other global technology companies Amazon is a large employer, with 590,000 workers in the US, 115,000 in Europe, and 95,000 in Asia. And it has hired many thousands more in the pandemic as its business has expanded still more rapidly.

Yet Amazon also displaces many jobs. Consider the construction workers who would have built shopping malls or offices that are no longer needed, or the shop assistants and security guards who would have been employed to work in them.

The economist Larry Summers has hypothesised that digital superstar firms like Amazon might be contributing to a slump in aggregate business investment and thus reinforcing a damaging “secular stagnation” in the global economy.

Amazon, as probably the most successful and dynamic company of our age, symbolises the immense opportunities and benefits springing from the digital revolution - but also its many pitfalls and complex regulatory, political and economic challenges.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments