In an out-of-the-way corner of Disney's vast headquarters in Burbank, California, there's a small and these days empty office that used to belong to Walt Disney's nephew, Roy. It is cone-shaped, like a vast sorcerer's hat, and lit by a three-ring chandelier which, if you stand in the right place, throws a silhouette of Mickey Mouse against the ceiling.

Roy died in 2009, around the time his one-time family firm plunked down $4bn (£2.5bn) for the comic book firm Marvel. This week, the company spent another $4bn to acquire Lucasfilm, which will now begin churning out new Star Wars movies for the summer blockbuster market.

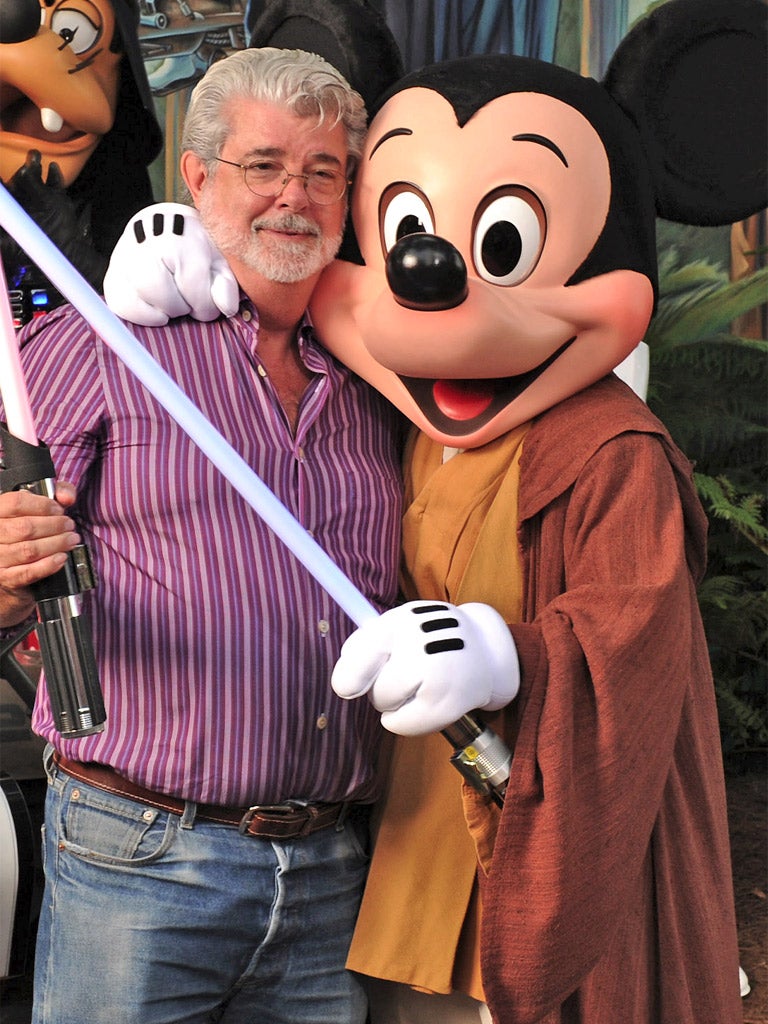

The deal is spectacular for George Lucas, who at 68 becomes one of the wealthiest men in showbusiness. Whether Disney can call it money well spent remains to be seen. The last Star Wars film, 2005's Revenge of the Sith, made $850m at the box office, against a budget of $113m (and marketing costs of roughly the same). If the next few instalments in Luke Skywalker's odyssey perform similarly, starting with 2015's Episode 7, the studio should recoup its investment in the mid-2030s.

That would be the logic of old Hollywood, at least. But today's Disney is unrecognisable from the empire Walt built. It exists in a different world even to the one in which Roy, the last of the family to serve on the board, served out his career. Today's movie studios aren't really designed to churn out films any more. That's why they produce fewer and fewer of them each year. Instead, they're in the business of creating "intellectual property".

Last year, for example, Disney's entire movie business generated income of around $600m. That's less than a tenth of the amount the firm earned from its media companies, which include the TV networks ABC and ESPN, and less than half the total profits it made from theme parks. It was a smaller amount even than the corporation made from "consumer products", the division which sells branded clothing and merchandise to its fans.

Yet if box office is nowadays a virtual rounding error to The Mouse House, Disney nonetheless lives or dies by its ability to create hit movies. Popular franchises provide the creative spark which lights up the rest of its highly lucrative empire. They inspire theme park rides and TV spin-offs, hit toys and video games. Without fresh films to drive it, Disney's hugely profitable wider business would stagnate.

Little wonder, then, that in a message to shareholders, Disney's chief executive Bob Iger stressed this week that Lucasfilm isn't really a production firm. Instead, he called it the business behind: "Seventeen thousand characters that inhabit several thousand planets spanning 20,000 years." The science fiction franchise offers, in Mr Iger's words, a whole new "universe" of commercial possibilities.

No-one knows exactly how lucrative this universe will be, since Lucasfilm is a private firm with opaque financials. However, USA Today reported in 2007 that Lucas Licensing, the commercial arm of Star Wars, generated $1.5bn that year. The Numbers, a Los Angeles firm which analyses the movie business, says its toy division, which makes action figures and plastic lightsabers, is worth $416m per annum.

Disney shares were nonetheless off around 2 per cent yesterday, reflecting consensus that Mr Iger had slightly overpaid. But in the long term, analysts agree with his logic.

Much like Pixar, the CGI powerhouse behind films like Toy Story and Cars, which Disney snapped up for $7.4bn in 2006, the Star Wars franchise could end up looking cheap at the price.

"We like this acquisition," was the take of Davenport and Co's Michael Morris, who predicted that from 2015 it will provide a "meaningful" boost to Disney's bottom line, particularly in international markets. "This [deal] is not inexpensive, and the valuation will be debated," he wrote. But its logic is sound.

Mr Iger's stewardship of Marvel, which he was widely said to have overpaid for in 2009, should also give investors cheer. Barclays Capital has maintained a relatively modest near-term price target for Disney of $52 per share (it's currently trading at $49) but is bullish about long-term prospects of Star Wars theme park rides and spin-off TV shows, along with toys and branded merchandise.

The deal "continues Disney's well-worn strategy of acquiring valuable intellectual property and monetising it better through its global, multi-product distribution engine", wrote Barclays.

So while Mickey Mouse may still be part of the scenery in Burbank, in creative terms, he's had his day: in the eyes of Mr Iger, the commercial future of Disney now rests on the rather broader shoulders of Iron Man, the Avengers, Luke Skywalker and Han Solo.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments