Houses to rise on ‘ghost sites’ as grocers leave the promised land

Building out-of-town superstores used to be the staple diet of the big supermarkets, but then the crash and the march of the discounters killed their development ambitions. Joanna Bourke reports on the new landscape for retailers and developers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Supermarkets have long been in the business of expanding their product lines in the pursuit of higher sales and profits, allowing customers to buy anything from lawnmowers to trampolines alongside traditional groceries.

But now they are also looking to sell an extremely valuable good: the unused land they have been sitting on since the financial crisis brought an abrupt halt to out-of-town expansion.

Tesco have sold the sites of 14 of its abandoned stores for £250m to a European real estate investor. Subject to local authority approvals, Meyer Bergman plans to build around 3,000 homes on the land in the south-east of England, London and Bath.

But it is not the only one of the big four supermarkets looking to strengthen its balance sheet by cashing in on unwanted real estate.

Tesco and its rivals no longer need all the acres they snapped up in the boom years before the recession bit in 2008. Since the crash, the big supermarkets have faced increased competition from the German discount chains Aldi and Lidl, and shifted their attention from out-of-town superstores to high-street convenience shops.

Consumers now are not wedded to the idea of a big weekly shop, with the result that the big chains have been left with “ghost sites” on which they have decided not to build.

At the start of 2015, according to the property agent CBRE, Asda, Sainsbury’s, Tesco and Morrisons owned more than 46 million sq ft of space that they had bought with the aim of building property– but less than 3 million sq ft was actually playing host to construction. The empty land could accommodate thousands of homes, boosting stock in a chronically under-supplied housing market.

Thomas Stevenson, a director at the property agent JLL, said companies have been increasingly looking at their property holdings in the last 18 months.

He added: “The Tesco transaction is a typical reaction we expect in response from the operators to the challenges they currently face from consumer and shareholder pressures.” In contrast, the relative newcomer Lidl said it had “a strategy to develop on all of the land that we purchase” – and that it wants to double its shop numbers to 1,200.

But how are retailers trimming their property portfolios, and will homes be built on all the land being sold?

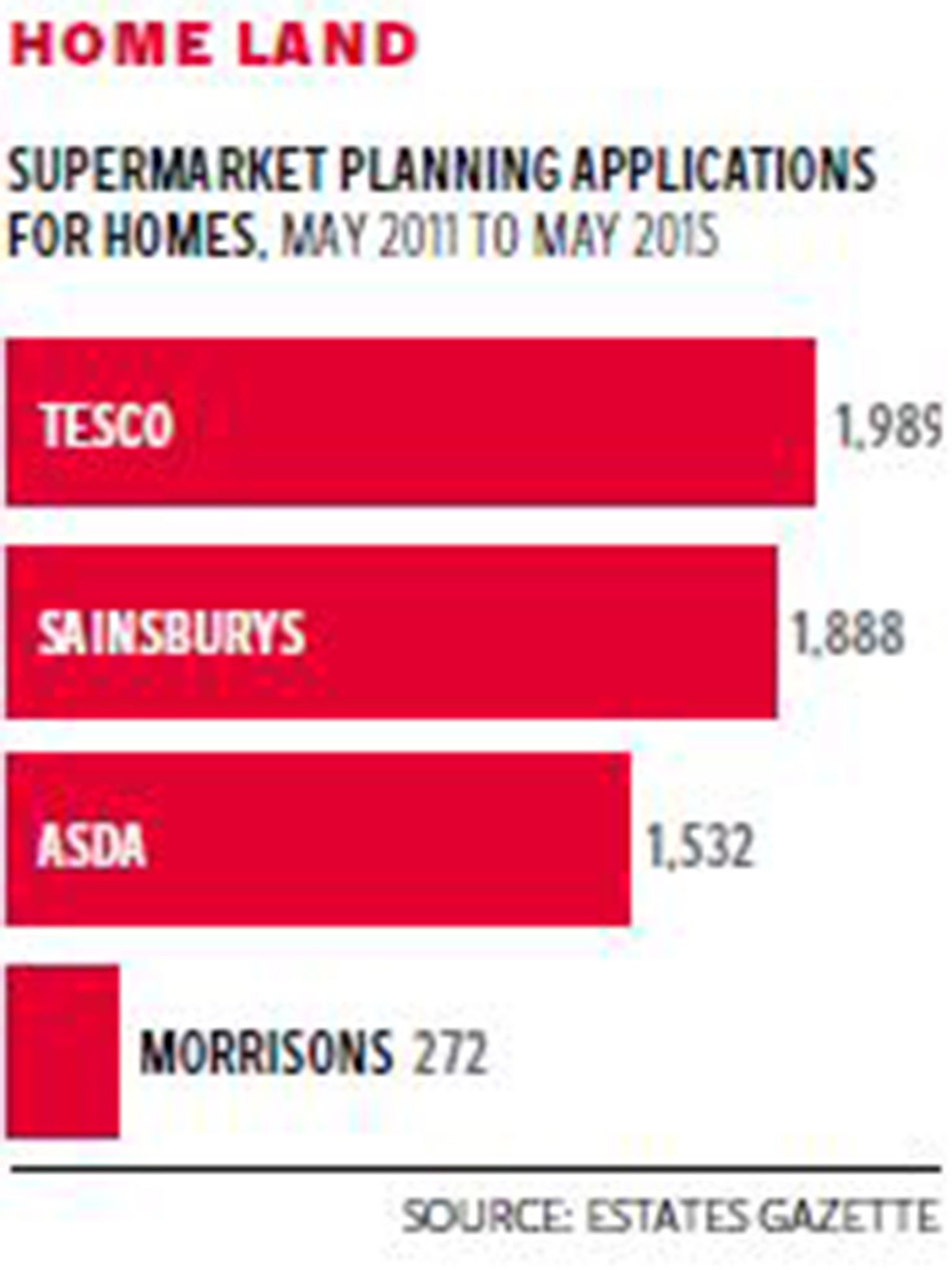

Research compiled for The Independent by the trade magazine Estates Gazette shows that in the four years to May 2015, the big four supermarkets submitted planning applications for 5,681 homes in the UK.

Rebecca Wood, at the magazine’s research team, expects more applications will soon be lodged, and that Tesco’s sale may be copied by rivals.

Ms Wood said: “With residential still one of the hottest property asset classes around, supermarkets are realising the goldmine they are sitting on. Tesco’s announcement shows it is realising it does not need to develop its own land bank to profit hugely from it.”

The sell-off will bolster the efforts of the Tesco chief executive Dave Lewis to strengthen the balance sheet. Given that the chain scrapped plans to build 49 new stores in January, more sales are likely.

Meanwhile the Morrisons chief executive David Potts last month announced the closure of 11 stores, saying “we cannot see any way through to make [them] viable”.

Morrisons and Tesco’s competitors are also likely to dispose of some land, experts anticipate.

And Adam Lawrence, chief executive of the luxury flats developer London Square, believes the sales will be very well received by the residential market, which is desperate to buy new land.

“We are keen to go shopping. There are some major sites owned by supermarkets in good locations in Greater London, ripe for residential and mixed-use development. And we are taking an active interest,” he said

Mr Stevenson at JLL added: “Supermarkets can maximise value through disposal of land suitable for residential development... significant value can be secured from cash-rich developers and investors seeking much-needed development opportunities.”

However, some property agents believe selling sites in the South-East will prove quicker and easier than in other parts of Britain.

But it is not all about selling big tranches of land. While Sainsbury’s is disposing of some sites, a spokesman said that on other land it is looking at developing residential projects in joint venture partnerships, rather than straight sales.

In London’s East End, the retailer is set to submit proposals for a new, larger replacement store alongside 600 homes. Sainsbury’s will take a share of the profits when the homes are completed and sold, giving it another financial boost.

Another way in which the grocers can make money from their buildings is by making sure they have less vacant space, believes David Gray, an analyst at the consultancy Planet Retail. He explained: “Mounting pressure from discount retailers, expansion of convenience stores and the growth of online mean that within a few years many of the big supermarkets will be in a position where their big out-of-town stores have some surplus space.”

Mr Gray added: “Over the last two years supermarkets have been experimenting with in-store concessions, and I expect we will see a lot more of these tie-ups as the grocers try to make the best use they can from redundant space.”

Among recent partnerships, Sports Direct has opened concessions in Tesco stores.

With data from the research firm Kantar Worldpanel last month showing that Lidl’s sales have grown by 16 per cent to reach a new market share high of 4.2 per cent – and Aldi’s growth up by 17.3 per cent for a 5.6 per cent share of the market – the supermarket war is heating up.

This may well lead to more of the big four checking out of chunks of their real estate holdings.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments