Harold Macmillan's Premium Bonds plan survives another cut

As Premium Bond prizes are reduced yet further below inflation, Simon Read asks why they remain so enduringly popular

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Harold Macmillan launched Premium Bonds in 1956 with a simple aim: to encourage the post-war generation to save. Sure, he also hoped the move would help control inflation, but while that intention is long-forgotten, the first part of Supermac’s plan continues to be a huge success.

An estimated 22 million people hold Premium Bonds. That’s around a third of the country. Between them they have £45.7bn invested in the Bonds.

But why? Yesterday, it was announced returns would be slashed by another 13 per cent from next month. The odds of each £1 Bond number winning a prize will fall from 24,000 to 1 to 26,000 to 1. But, in fact, there’s no guarantee that Bondholders will actually win anything, ever, as the prizes are drawn randomly.

Let’s face it, the prize fund interest rate quoted by National Savings & Investment – the Government department that runs the Bonds – is not really relevant. It’s falling from 1.5 per cent to 1.3 per cent from 1 August, but for millions of people it’s zero.

For the Premium Bonds are no more than a gamble or lottery. While there are chances of becoming a millionaire in the monthly draw, you are more likely to win nothing. In fact if you win nothing you’re actually losing money because of the inflation effect. The consumer price index (CPI), a measure of inflation, climbed to 2.9 per cent this month, which means £100 a year ago is now worth £97.10 in real terms.

In fact if you had bought £100-worth of Premium Bonds back in 1956 and had won nothing since you’d be more than 2,000 per cent worse off because of inflation rises since. That 1956 £100 has a buying power now of less than a fiver. Or, to put it another way, if your savings had kept pace with inflation you’d be sitting on more than £2,000 now.

So why do millions of people sit on their Bonds losing money? Is it just the prospect that they might one day become a millionaire? If so, why not just do the lottery?

The psychology of saving is complicated. Millions of ordinary savers want security and Premium Bonds do, in effect, offer that. First, the cash is protected by the Government – so, unless the country goes bust, the money will always be there. Second, you can get at your money at any time by cashing in your Bonds.

Compare that with the Lottery, where you have to hand over money for every draw to be in with a chance of winning. That’s a quick way to lose a fortune rather than gain one. At least with Premium Bonds your money can buy you a lifetime’s entry into the millionaire dream.

But is that reason enough to buy one? Wouldn’t most investors be better off putting their money into high-rate savings accounts? If there were high-rate savings accounts that would be true. But if you want a deposit account that pays a higher rate than inflation you’d now need one that paid 3.63 per cent. If you’re a higher-rate taxpayer you’d need to find an account paying at least 4.83 per cent.

Interest rates analysts Moneyfacts say of the 817 ISA and non-ISA accounts in the market today, there is not a single savings account that taxpayers can choose to negate the effects of tax and inflation. Not one.

So, with all simple savings accounts losing money in real terms, Premium Bonds don’t look so bad. In short, if you took your cash out, there’d be few attractive homes for it.

But does that make Bonds an option that new investors should consider? “Premium Bonds are useful for higher rate taxpayers for use as a short-term cash park,” says Danny Cox of Hargreaves Lansdown. “Prizes are tax-free and you might win more than the equivalent of the after-tax interest on a deposit account. However, I do recommend that people use their cash ISA allowance first.”

Premium Bond payouts are tax free and equate to a return of 1.625 per cent for a basic rate taxpayer, 2.17 per cent for a higher rate tax payer and 2.36 per cent for a 45 per cent tax payer, says Patrick Connolly of Chase DeVere.

“These rates, particularly for higher and additional rate taxpayers, remain very competitive in the savings market,” he says.

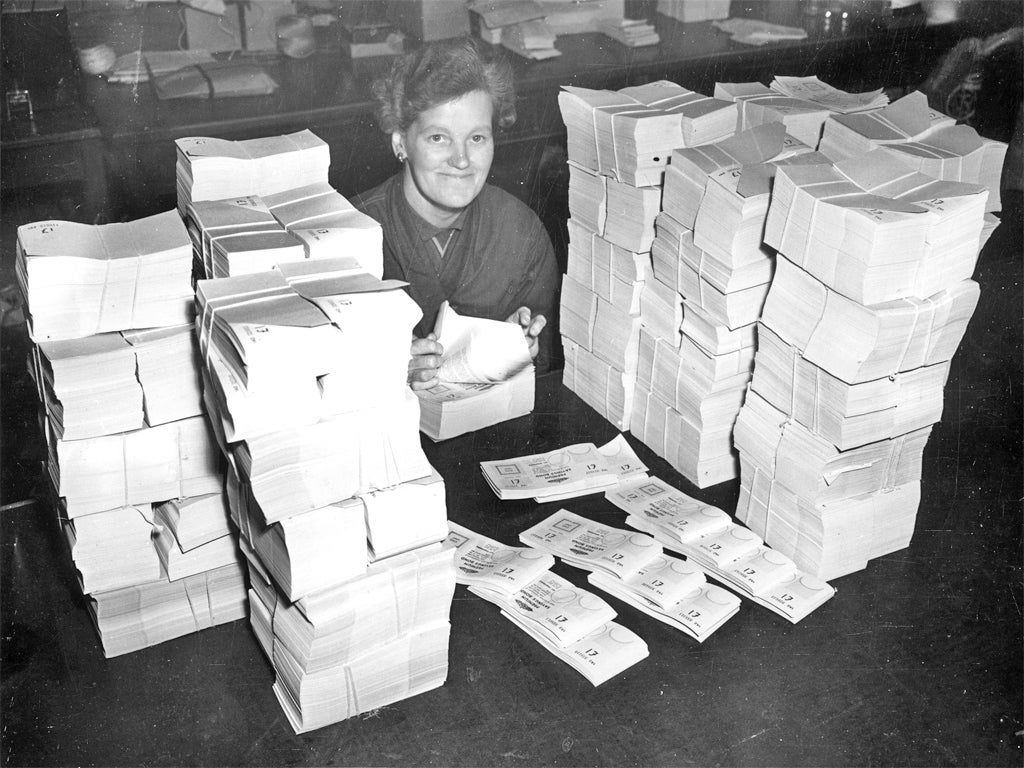

An all-star launch: How bonds started back in the 1956 budget

It was Budget Day on 17 April 1956 when the then Prime Minister Harold Macmillan announced the launch of Premium Bonds.

They were put on sale for the first time on 1 November that year and quickly gained huge popularity with a range of celebrities lined up to announce winning numbers, including the likes of stars like Bruce Forsyth, Bob Hope and Dame Judi Dench.

They became a very popular way for grandparents – and other members of the family – to gift cash to a newly-born child with the bonds being available from just £1.

That’s changed now and the minimum investment is £100 with a maximum £30,000 allowed to be stashed in the tax-free bonds and eligible for prizes in the monthly draw. Despite being such an old scheme, popularity of the bonds have soared in the last 20 years with the amount invested rising from £4bn in 1994 to ten times that today.

Even with today’s cut, Premium Bonds will still pay out around 1.7m prizes each month and have a monthly prize fund of £49m. However in June 2006, a couple of years before the 2008 crash, the total monthly prize pool stood at £76.6m, and the interest rate quoted then was 3 per cent.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments