Don’t just do it: break point for glory-hunting sponsors

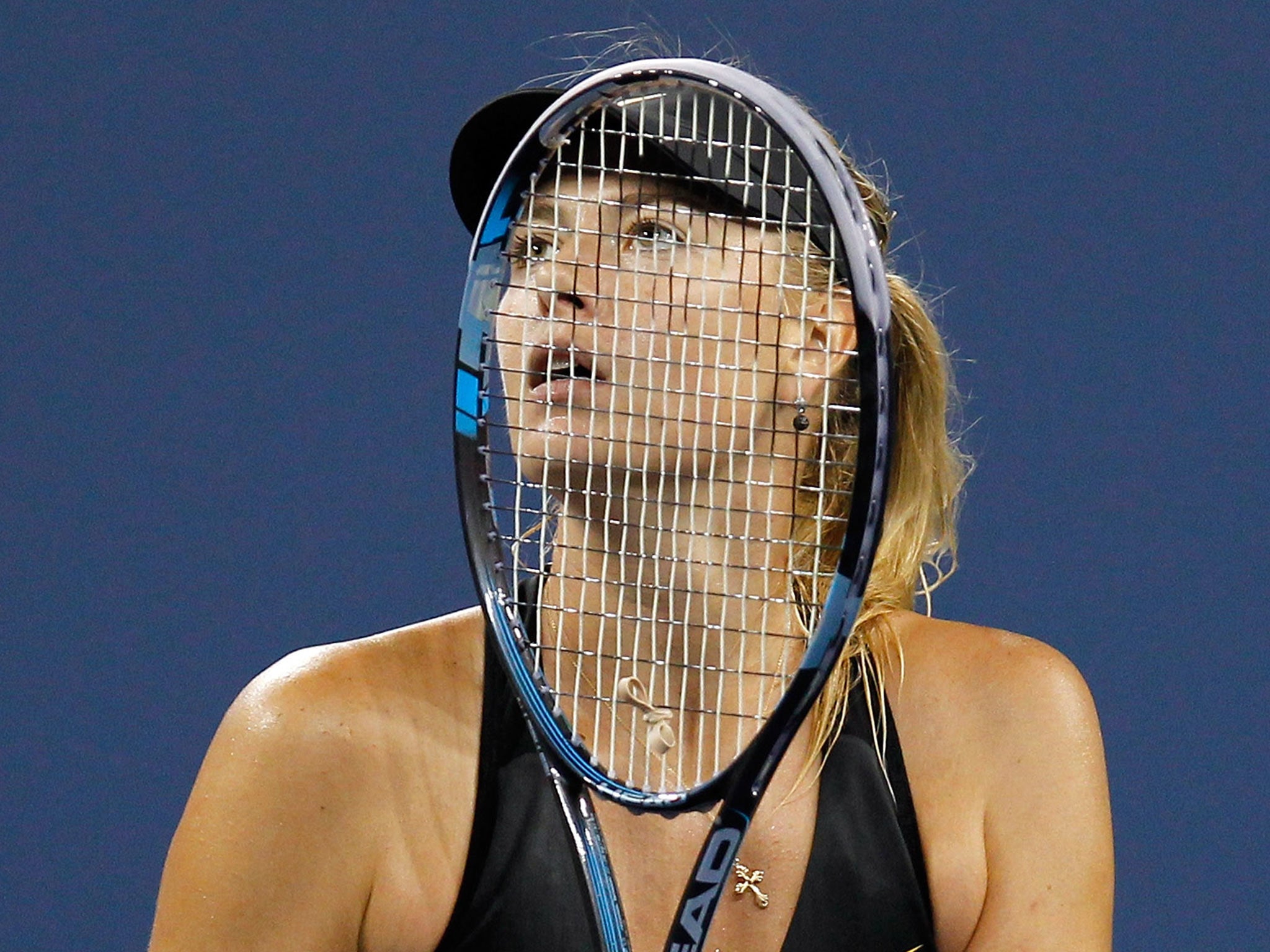

Maria Sharapova is only the latest example of an endorsement gone wrong. Brands never believe that the worst might happen

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“I did fail the test and take full responsibility for it.”

The revelation of that failed drugs test had far wider implications than Maria Sharapova could ever have imagined when she uttered those words to the world’s media on Monday evening.

A ban beckons for the Russian tennis star, but the long list of sponsors that back the 28-year-old are already counting the cost of the scandal.

Nike, the sportswear giant that has an eight-year deal worth £50m with Sharapova, was quick to suspend its sponsorship, while Swiss watchmaker Tag Heuer took little time in ending talks over renewing its endorsement. The German sports car maker Porsche said it was “postponing planned activities” until the situation becomes clearer.

Sharapova’s other sponsors – the sports equipment company Head; Evian, the mineral water group; the cosmetics and fragrance seller Avon; and Tiffany, the jewellery company –are yet to publicly state their positions on the matter. But it is likely that their lawyers are running a rule over the fine print of the contracts.

Early estimates suggest that if Sharapova – the highest-earning woman in sport, raking in £16.1m last year from endorsements alone – is given a four-year ban then it could be the end of her career. And in that eventuality, she stands to miss out on as much as £100m, including tournament prize money.

But for global brands and their reputations, the potential losses are far greater.

Andy Sutherden, global head of sports marketing and sponsorship at the marketing group Hill+Knowlton, says that while lawyers are becoming an increasingly important part of the sponsorship process, big consumer businesses are still not doing enough to protect themselves from potential scandals.

“There is still too much ambiguity in modern-day sponsorship contracts when it comes to what represents a breach of contract,” says Mr Sutherden, whose clients include Nike’s main rival Adidas.

“Any shade of grey in a contract presents a reputational risk for the company in question. Unless it is unambiguous as to what represents a trigger to terminate or not, a company is always left in a very dangerous halfway house between continuing or severing links.”

He thinks there are two skills still being honed in modern sponsorship. The first is negotiating robust contracts that allow big companies to part ways if one of its ambassadors attracts unwanted headlines. The second is the ability of a business to ensure its reputation remains intact even if they do.

“The irony to any sports fan is acute. The reason why a company associates itself with an individual, a team, or a competition is that it provides a halo effect on them and their business,” says Mr Sutherden, who adds that modern-day sponsorship presents “as much reputational risk as it does opportunity.

“Companies have been very good historically in preparing for the best; they have not necessarily been as good at planning for the worst.

“It has always staggered me that a company will be very happy to live in the honeymoon period of sponsorship without giving much regard to the ‘what if it all goes wrong?’ scenario.”

The past few years of sponsorship deals certainly read like an A-Z of sporting scandals – many of which Nike has been at the heart of.

Without Tiger Woods, the American company’s golf brand would have been nothing – but their relationship has certainly spent plenty of time in the rough.

Nike stood by the golf star during his fall from grace after he admitted to cheating on his former wife.

However, it drew the line at drugs when the disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong was uncovered as a serial cheat. More recently, the brand cut ties with Paralympic athlete Oscar Pistorius, who killed his girlfriend Reeva Steenkamp, and Manny Pacquiao after the boxer said in a television interview that gay people were “worse than animals”.

Adidas is the one feeling the heat from the Fifa corruption scandal. Along with Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Visa and Budweiser, it has threatened to walk from its sponsorship deal unless football’s governing body undergoes drastic reform.

It is not just sports stars that risk tarnishing the reputations of global brands. Supermodel Kate Moss famously tested the nerves of executives at the luxury fashion group Burberry, Swedish clothing retailer H&M and French high-fashion house Chanel when her cocaine use was exposed more than a decade ago. They all subsequently dropped Moss, but the fashion and cosmetics world is fickle and she now has deals with Rimmel, Dior, Mango, and of course, Burberry.

Are some brands then too quick to dump their ambassadors? The risk in the modern world, driven by instant social media, is that questions would have been asked of Nike if it had failed to act immediately. Failing to take any action over Sharapova would have been viewed in the same way as a decision to support her.

Mr Sutherden suggests Nike may have informally spoken to Sharapova’s other sponsors before making the decision to suspend sponsorship.

Huge global brands are racing to sign up teenage sports stars in the hope they will become the next Cristiano Ronaldo or David Beckham. The landgrab for young talent increases the likelihood of PR disasters happening more frequently, but it also spreads the risk, especially for sporting brands such as Nike. That way, if one reputation is tarnished, they can quickly change the face of the brand.

Listed companies such as Nike also have to consider the views of shareholders, which in the sportswear company’s case are some of the biggest asset managers in the world. BlackRock and Fidelity together own Nike shares worth around $10bn (£7bn).

But on the shop floor it can also hurt morale among staff – upset that their employer will continue to support disgraced sports stars, but will not think twice about slashing thousands of jobs when times are tough.

“To see your own business spend a lot of money on something that only brings negative headlines can lead to diminished productivity,” says Mr Sutherden. “I don’t think it’s dramatic to talk about the effect on the inside of an organisation as well as on its external reputation.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments