CPIH: What is this new official inflation measure and why should we care?

It refers to 'consumer price inflation including owner-occupiers’ housing costs' and the regulator thinks it deserves the status of 'national statistic' again

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Britain’s official statistics watchdog, the UK Statistics Authority, ruled on Monday that a measure of inflation known as “CPIH” can once again be given the status of “National Statistic”.

But why does this matter?

And is it likely to affect ordinary people?

What is CPIH?

It refers to “consumer price inflation including owner-occupiers’ housing costs”.

Despite the name, it is not a measure that includes changes in house prices.

It’s essentially the conventional and familiar measure of UK consumer price inflation (the Consumer Price Index) produced each month by the Office for National Statistics but adjusted to reflect changes in average residential rents.

These rents are used as a proxy measure of how much it would hypothetically cost homeowners to rent their own homes.

Why is this adjustment an improvement?

In the UK, where home ownership is still very widespread implicit owner-occupiers’ housing costs are large.

The ONS estimates that they account for more than10 per cent of total household expenditure.

And this implicit expenditure is not captured in the existing CPI.

An official review in 2015 by Paul Johnson recommended that the CPIH be used instead of the CPI to better reflect the cost pressures facing UK households.

CPIH also includes council tax, unlike CPI.

Why did CPIH lose its official status?

Because statisticians found problems in the way private sector rents were being calculated by a separate government agency called the Valuation Office Agency (VOA).

If this data was unreliable it naturally followed that the CPIH was also unreliable since the ONS relied on VOA data to calculate the owner-occupier housing costs element of the CPIH.

So the UK Statistics Authority stripped CPIH of its official statistic status in 2014 while the problems were addressed.

Now (three years on) the regulator thinks these issues have been resolved and CPIH can be considered an official statistic once again.

But what practical difference will this make?

When Mr Johnson published his 2015 review he expressed the hope that the Bank of England would soon start to target CPIH rather than CPI when setting interest rates.

That was never going to happen while CPIH was not considered reliable enough to be a national statistic.

But now that it is the way is open for the Government to mandate the Bank to target CPIH instead.

So the Bank's Monetary Policy Committee could target 2 per cent inflation as measured by the CPIH, rather than the CPI.

This could have implications for the path of interest rates, which would impact on many people’s monthly mortgage repayments, the value of the pound and also the price of many financial assets.

But do the two measures actually diverge much?

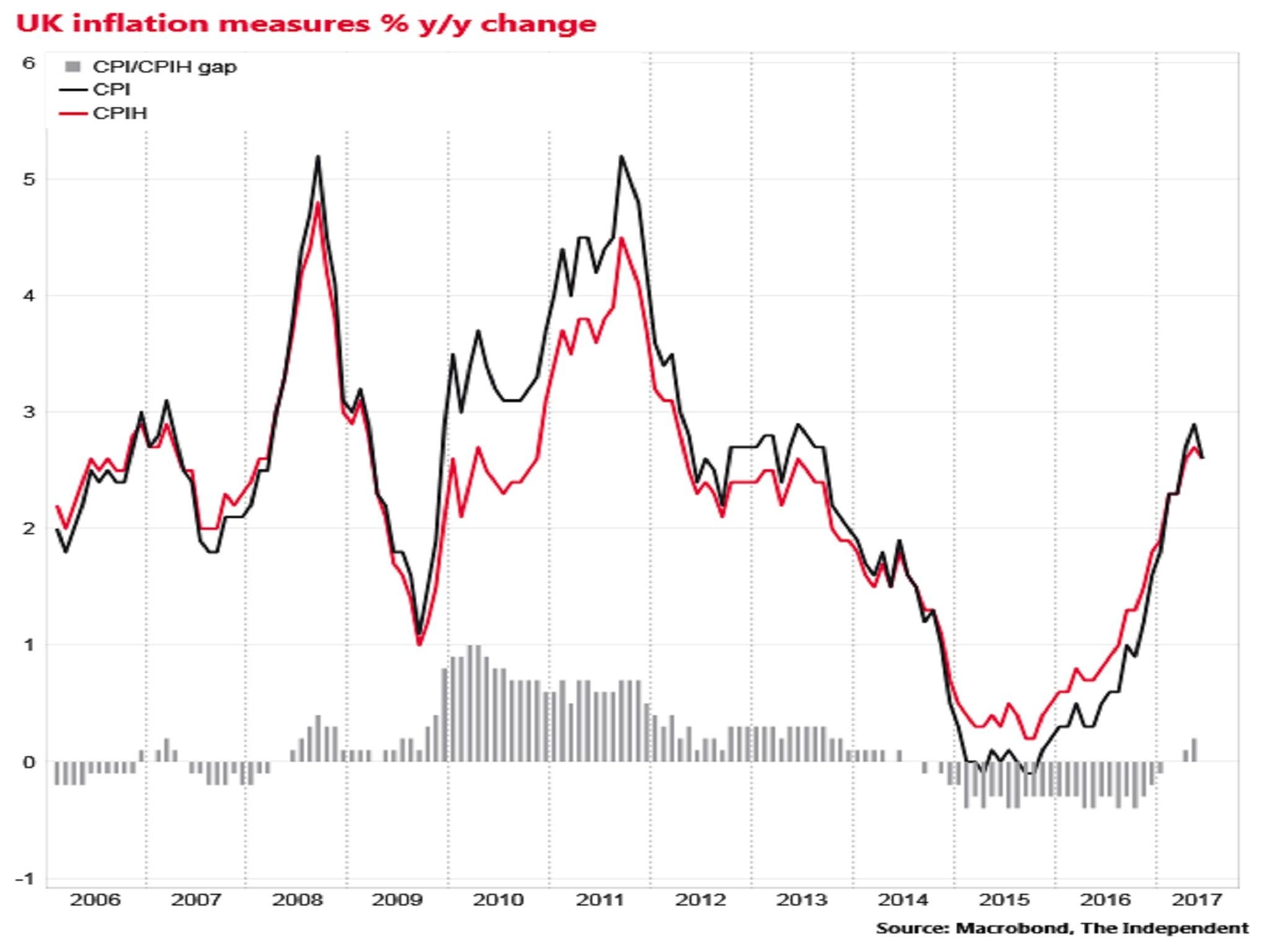

The back series of CPIH has shown divergent growth from that of the CPI over the years.

The divergence has not been enormous, but it is not insignificant.

The average absolute gap (i.e regardless of whether it is higher or lower) has been around 0.29 percentage points in each month since 2006.

CPI growth tended to be higher between 2010 and 2013 (as much as 1 percentage point higher). In 2015 and 2016 CPIH grew more rapidly.

The two measures are currently both at 2.6 per cent but in May the CPI grew by at 2.9 per cent but the CPIH by only 2.7 per cent.

What about RPI?

Good question.

If there are statistical problems with the CPI these are as nothing compared to the RPI measure, which uses a discredited formula for calculating the rate of price rises.

The RPI was stripped of its own national statistic status in 2013 by the UK Statistics Authority.

Yet some government spending remains linked to RPI, including the repayments on inflation-linked government bonds.

Student loan repayments and permitted annual rail fare rises are also linked to the measure.

The RPI has been consistently higher than both the CPI and the CPIH since 2010 and currently stands at 3.5 per cent.

This all means the Government spends excessive amounts of taxpayers’ money on bond repayments and that commuters and students pay more than they would if the government used the CPI or CPIH benchmark instead.

So why not just scrap RPI?

The UK Statistics Authority and the ONS say it’s up to the Government to stop using the RPI.

Others say the statistics agencies should force the Government’s hand by simply ceasing production of the RPI measure, or correcting the formula used to calculate it.

Despite the deadlock, the simple reality is that the impact on most people of the Bank of England moving from a CPI to a CPIH inflation target would be considerably smaller than from the Government using CPI/CPIH instead of RPI as an official price index for all spending commitments and price regulations.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments