‘They just don’t care’: Millions of garment workers facing destitution as Britain’s high street billionaires fail to honour contracts

Coronavirus could be the final nail in the coffin of the unsustainable fast fashion industry. But with some retailers failing to share the economic pain with suppliers, its demise could be fatal for millions of workers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In his factory in Chittagong, Bangladesh’s main port and trading hub, Mostafiz Uddin has a mountain stacked high of 100,000 pairs of jeans with nowhere to go.

The piles of denim – stonewashed, black, skinny fit, turn-ups, shorts and more – had been destined for shops on UK high streets owned by Philip Green’s Arcadia empire, to satisfy our seemingly unquenchable thirst for fast fashion.

But it appears we may have realised we didn’t need them after all. As millions of us sit at home under lockdown conditions, and thousands of others have lost their jobs, demand for clothing has collapsed. Britons bought 35 per cent less clothes in March than in the month before – and that was before lockdown measures were fully introduced.

Extrapolate that trend across the global apparel trade and the numbers are truly staggering. The industry is worth $1.5 trillion (£1.2 trillion) a year – about half the size of the UK’s entire annual economic output. Most of those clothes are made in poor countries and bought in rich ones. Low prices have been key.

Some retailers have sought to share the unprecedented economic pain of Covid-19 with their suppliers. Sweden’s H&M took the early lead, saying it would honour all existing contracts for goods ordered. Zara owner, Spanish giant Inditex, followed suit with a similar pledge.

Others, such as Primark, took a hard-line approach, cancelling hundreds of millions of pounds of orders before partially backtracking in the face of a surge of bad publicity. UK retailer Next agreed this week to honour some of its orders.

Asda, owned by US retail giant Walmart, is enjoying a bumper period of trade, but decided to pay its suppliers half for finished garments and 30 per cent for unfinished ones. It’s since softened some of its demands.

Then there are the worst offenders who are still refusing to budge.

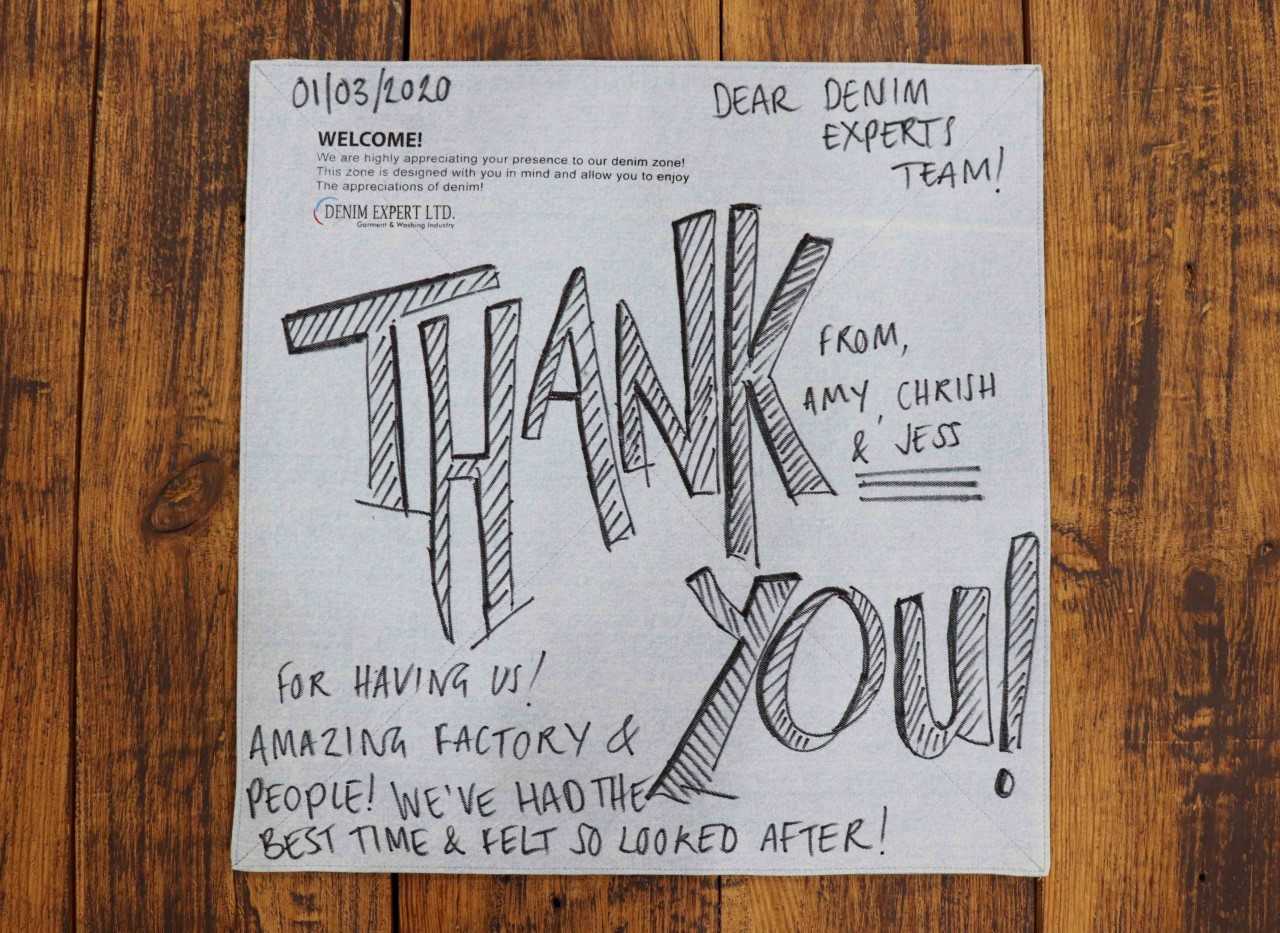

Philip Green’s Arcadia Group, which owns brands including Dorothy Perkins, Topshop, and Miss Selfridge, has been among them. Uddin’s company, Denim Expert, received terse letters in March and April, stating bluntly that orders for hundreds of thousands of pieces of clothing had been cancelled with immediate effect.

Items already shipped would be subject to a 30 per cent discount, Arcadia said, in a few lines of text that more than wiped out Uddin’s mark-up of between 5 and 10 per cent.

“You can make better margins,” he says. “But not if you pay workers properly and do things sustainably, as we do.”

All other Arcadia orders that have already been made, including some that have already shipped, were cancelled. There was no negotiation. It was an order.

Even more egregious are the demands of Edinburgh Woollen Mill (EWM), a stable of high street names that includes Peacocks, Jaeger and Bonmarche among others. It is owned by retail billionaire Philip Day and operates more than 1,000 stores across the UK.

In March, EWM cancelled orders with Uddin’s company for tens of thousands of items and demanded 70 per cent discounts on millions of pounds worth of goods that had already been made, handing a huge loss to suppliers.

These orders were not for seasonal summer items that Peacocks could not sell, but for standard lines of jeans that EWM did not want to have to pay money to store in warehouses. Even in the current circumstances, such huge reductions were unheard of.

“This is the worst in the industry,” says Uddin. “Nobody asks for 60 to 70 per cent [discount].”

Environmental and humanitarian disaster

With no buyer for his jeans and little room for storage, Uddin fears a significant proportion of the fruits of his workers’ labour will end up in landfill. “It’s a huge environmental problem,” he says when The Independent spoke to him on International Workers’ Day.

Garment industry workers, already among the most precarious in the world, face destitution with no social security safety net.

Uddin prides himself on treating workers ethically and with respect. So far, he has continued to pay his 2,000 mostly young, female employees so that they in turn can continue to feed the thousands more mouths who depend on their modest incomes. Others have not been able to, or have chosen not to, do so. And time is fast running out.

The apparel business runs on small margins and lots of credit. As orders are cancelled and banks begin to call in their loans a humanitarian disaster that is hitting Bangladesh at a particularly poignant time.

It’s Ramadan, the holy month in which Muslims – including Uddin’s 2,000 staff – devote themselves to prayer, fasting and charitable deeds.

Seven years ago this month, emergency workers were trawling through the rubble of Rana Plaza, an unsafe and poorly maintained garment factory in Dhaka that collapsed, crushing 1,137 people to death. In early May 2013, weeks after the initial collapse, the search was finally called off and the industry vowed, “never again”.

Philip Day – ‘saviour of the high street’

EWM is owned by Philip Day, a fashion billionaire who worked his way up from a childhood on a Stockport council estate to build an estimated £1.2bn fortune. He owns a castle in Carlisle, officially lives in Switzerland and spends a lot of his time in Dubai, where his acquisition company Spectre is registered. He reportedly bought his first helicopter from Sports Direct tycoon Mike Ashley.

Like Ashley and Green, Day has been phenomenally successful in building a huge retail operation. It boasts more than 1,000 stores and over 25,000 staff. While his profile may be lower, his methods are similarly controversial.

Companies who have not committed to honouring contracts for existing orders

Arcadia

ASOS

Bestseller

C&A

EWM/Peacocks

Gap

JCPenney

Kohl’s

Mothercare

Primark

Ross Stores

Sears

Under Armour

Urban Outfitters

Walmart/Asda

Source: Workers' Rights Consortium (as of 5 May 2020)

His reputation for buying up struggling high street names and turning them around has landed him with a reputation as a saviour of Britain’s ailing high streets. However, some view him more of an asset stripper, who gets hold of failing brands while using insolvency laws to ensure that suppliers are left with nothing.

His takeover of Jaeger attracted criticism from suppliers and some observers. With the high-end fashion brand failing, he purchased the brand name but did not pay for the company’s assets. When the company fell into administration shortly afterwards, suppliers who had already handed over stock to Jaeger received just 2p for every pound they were owed.

Critics suggest he is using similar “financial engineering” to turn a profit from struggling Bonmarche, the clothing retailer Peacocks bought for just £5.7m last year which then went into administration. A spokesperson for EWM said Mr Day lost out financially from the administration.

Suppliers in Bangladesh and beyond now allege that they too are receiving unfair treatment from Mr Day’s company.

“I’ve been told by Peacocks the goods are cancelled,” says Uddin. “We told them that we have bought raw materials from the factory but they are not replying to our emails. We get automated responses. They just don’t care.”

We do not want charity. We just want companies to pay their bills and respect their contracts

Arcadia is little better, says Uddin. “They have cancelled around $2.5m of orders. This will be a disaster for me and my workers.”

A spokesperson for Peacocks said the company contacted suppliers as soon as possible to provide them with options once it was clear high streets were seeing a downturn in sales. “This was an essential step as, otherwise we would be taking delivery of stock that we simply could not sell,” the company said. “We have since entered negotiations with suppliers individually, with the options tailored to the individual suppliers.”

Arcadia did not respond to requests for comment.

Across Bangladesh, companies have cancelled an estimated $3.5bn of orders. For a country that generates the majority of its export income from clothing sales, this could spell disaster.

Bangladeshi factory owners like Uddin are now effectively being asked to subsidise Philip Green, the former king of British retail, and his apparent heir, Philip Day.

Seven years after Rana Plaza, Uddin, like many manufacturers in the trade, feels he is treated with little more respect than he was back then.

“There was no negotiation, no discussion, no partnership or respect. No co-ordination. Nothing. You accept the discount or take the goods. How can I take the goods when they’re already in a UK port?” he asks.

“We have bought the raw materials, we have produced the garments, we have invested the money and we will not be able to survive.

“We will literally die. It will be impossible for us to handle this. Our workers will be suffering a lot. I have no words to express what it will do to us.”

“The goods are ready. They should take the goods. If they have a problem they can wait for a month or for 45 days. There should be some discussion but they just sent an email saying that the orders are cancelled. How is this possible?”

Since February, buyers for Uddin’s company have cancelled around $10.5m of orders – a big chunk of his annual turnover. Globally, the Workers’ Rights Consortium estimated that $24bn of orders have been cancelled – though this has likely reduced as some brands have made new commitments in the face of a wave of bad publicity.

Global clothing buyers have made big claims in recent years to have cleaned up their act.

Yet, even before the coronavirus hit demand, increased pressure to cut prices had already seen wages in the sector fall 15 per cent. In the past two months, an estimated 60 million low-paid garment industry workers have had their livelihoods put at risk as major brands and retailers have sought to dump the financial burden of the crisis on those further down the supply chain.

Peacocks

EWM says it had no choice but to demand discounts. Its latest accounts published in December showed that, unlike many retailers, it had no bank debt and had turned a healthy profit. It decided not to pay a dividend to shareholders as it wanted to pump money into making more acquisitions.

Uddin believes the company is trying to take advantage of the coronavirus crisis to obtain massive discount.

Peacocks says it gave suppliers three options: They could keep hold of the stock and sell it locally; they could accept a large discount or they could be paid for it when Peacocks eventually took delivery and sold the stock to consumers.

These aren’t really options at all, according to Uddin. Like most garment manufacturers, he borrowed the money to make the jeans (which were ordered back in August last year). He can’t wait for Peacocks to potentially sell them in a year’s time before payment. His workers need wages now.

“My workers’ lives are under threat because we are an export company,” he says. “We only get the money when we complete the export. If we don’t export we don’t get the money.”

Inditex, which owns Zara, has by contrast, used its strong pile of cash to honour contracts with suppliers.

Solutions

An immediate solution is needed to prevent millions of impoverished workers becoming destitute, says the Workers’ Rights Consortium.

The power relationship between buyers and suppliers in the fashion industry is among the most unequal of any sector. Contracts reflect that inequality with buyers dictating whatever terms suit them. Legal remedies are too costly and take too much time, as buyers are well aware.

There are signs that bad publicity is beginning to shame retailers into action. Some companies have agreed to step in to pay wages of some workers but this amounts to only a small fraction of the orders cancelled, says Olivia Windham Stewart, a leading campaigner on the issue.

Many other retailers, including John Lewis, Gap, Arcadia Asos, Sports Direct, have yet to make firm commitments.

“We do not want charity,” says Uddin. “We just want companies to pay their bills and respect their contracts.”

Beyond the immediate crisis, the situation may only be fixed by legislation in wealthy countries forcing companies to take responsibility for their supply chains. At present, they remain almost entirely unaccountable.

Last year, the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee recommended that the UK government should legally require fashion retailers to take responsibility for environmental and human rights issues in their supply chains.

The government rejected all of the recommendations.

But change may finally be coming. Last week, the EU commissioner for justice announced the Commission would introduce “mandatory corporate environmental and human rights due diligence” across all sectors. Perhaps, says Olivia Windham Stewart, the UK will have to follow suit.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments