Brexit: UK businesses battle with red tape and higher costs as trade with EU plunges

Firms across the country have been hit by a huge burden of extra forms, declarations and rules that are making trade more difficult and more costly, writes Ben Chapman

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A dramatic 41 per cent plunge in exports of goods to the EU in January is the first official indication of the profound impact of Brexit on UK trade.

But the effects for businesses were clear before the new year as they struggled with a mountain of extra paperwork, electronic forms and safety checks.

While the government sought to downplay alarming trade figures on Friday, claiming that the record fall was due to temporary factors including Covid-19 lockdowns, firms across the country tell a different story.

Some of the effects are probably short-term, and trade experts are expecting a partial recovery over the coming months but businesses are now burdened with significant extra costs and some feel guidance from the government has been severely lacking.

The “constant uncertainty, amended timelines and unprecedented last-minute adjustments have not made for an easy transition”, says Nick Finbow, sales director of PML, a logistics company that specialises in moving perishable goods.

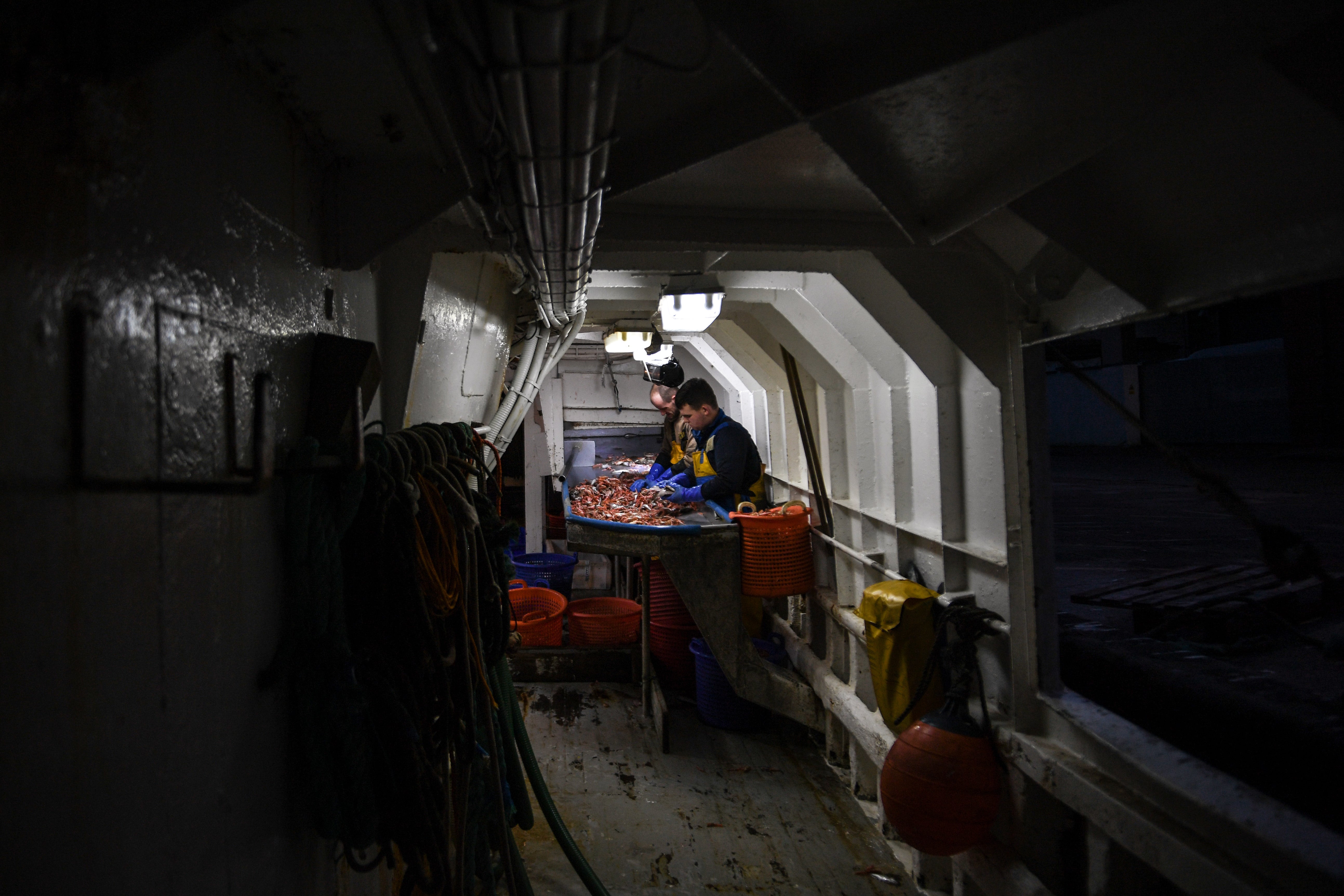

Scottish shellfish were among the first and most acutely affected exports with some hauliers having to throw lorry loads away at the border due to incorrect customs declarations. Exporters have also struggled to get their produce to EU markets in time because of delays.

PML has avoided some of these issues largely because the company started preparing for Brexit in March 2017.

But the impact of Brexit is undeniable. Official figures show food and live animal exports to the EU fell by 64 per cent in January.

Even in this tough environment, PML has moved 700 to 800 lorries per week both into and out of the EU this year and Finbow says adapting to the new rules has been “fairly seamless”.

However, there have been frustrating problems. “We’ve had instances where we have submitted the relevant documents as specified by the government authorities, only to be advised that we need to provide other paperwork,” says Finbow.

“We’ve then gone back again with the original documentation, which was suddenly deemed acceptable. On one occasion, a driver made three separate approaches to get through at Eurotunnel and it was only on the third try that he was given clearance.

“Clearly, there is an unacceptable lack of understanding and training at some ports which is placing further pressure on the system.”

Anita Rae, founder of healthy energy drinks maker Crave, has found a similar lack of knowledge at HMRC, where staff on helplines have often not been able to answer her queries about customs.

“You can be as prepared as possible but there are still plenty of problems,” she says.

“There is a lot of unclear guidance around customs declarations. The customs officers in the UK and in EU countries do not know what’s needed. For us, it is a big problem and a cost to try to understand.”

Labelling requirements for food are also burdensome. Before 1 January, Crave could send products labelled in English but now they have to be in the local language before they arrive at their destination, adding further costs.

Crave has had to absorb this outlay for orders agreed with customers before 31 December, but may be forced to raise prices in future.

The company’s products are made in Austria before being imported into the UK and shipped all over Europe. Like many entrepreneurs, she has set up a subsidiary within the EU.

As a small business, the additional costs and workload involved in trying to comply with the new rules are significant.

Rae is calling out for a central database providing answers to businesses’ many questions about importing and exporting after Brexit.

‘Nothing positive has happened’

Ian McCulloch, founder and managing director of gin maker Silent Pool Distillers, says “nothing positive has happened yet” for his company as a result of leaving the EU.

“We have increased export paperwork, cash is tied up in raw materials from the EU as we have to hold greater stocks; there has been a massive increase in shipping costs, driven in part by the government using containers as temporary storage at ports,” he says.

He adds: “No one has given us a roadmap to the ‘sunlit uplands’ or even told us ‘here’s a list of things you couldn’t do before but can do now’. To be honest, apart from a theoretical sovereignty issue, I can’t currently see any benefit.

“This may be about messaging but you would have thought four years down the line the government would have counterbalanced all of the stress and chaos of Brexit with at least a glimpse of some upside.”

Simon Campbell, managing director of Portview (a Belfast-based luxury fit-out firm), says Brexit has added 20 per cent to the burden of administration his company faces “for no added value”.

The company does a lot of its work in London where it has taken on jobs including fitting out Selfridges and Harvey Nichols as well as the corporate hospitality sections of major sports venues.

Bringing materials to London has been a simple process but returning from Great Britain to Northern Ireland now requires a significant amount of administration despite government assurances that there would be no border down the Irish Sea.

Portview has had to register with the government’s Trader Support Service. Each time the firm needs to get through a port, it makes bookings on an IT system that generates a number. The company then has to itemise everything that was in that vehicle and notify HMRC. Up until 31 December, this process had been as simple as driving on and off a ferry.

“It’s been a very steep learning curve,” he says. “There’s a paperwork headache and a lot of detail we have to follow up with.”

Importing goods has been challenging with longer lead times, partly due to backlogs caused by Covid and partly due to Brexit.

Campbell was told that registering with HMRC would take a few hours; instead it took several weeks, meaning Portview initially had to “piggyback” on the registration of a delivery company it uses regularly. He also found the government provided little help.

“It was the blind leading the blind initially. The government was playing catch-up and now that is out of the way we are just left with the bureaucracy of working through the different portals to get goods moved into Northern Ireland.”

David Wilson, managing director of Vanden Recycling, found that hauliers simply wouldn’t move the company’s goods when the transition period because of uncertainty about the new requirements.

“When we could ship we found in January a high level of confusion in our customer base some of whom were going back to customs clear procedures from a generation ago and asking for documents that haven’t existed in decades,” he says.

While that situation could be described as a “teething problem”, the new reality of trade with the EU is a permanent one: “There is a much higher level of friction than pre-Brexit,” says Wilson.

“We will get on top of that but there’s a consideration that isn’t much spoken about. Right now demand for our product is high and we have the goodwill of customers on our side.

“We work however in a commodity market, so what happens when we have to push harder for sales? Why will our EU customers buy from us when they have easier internal EU options? That worries me hugely.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments