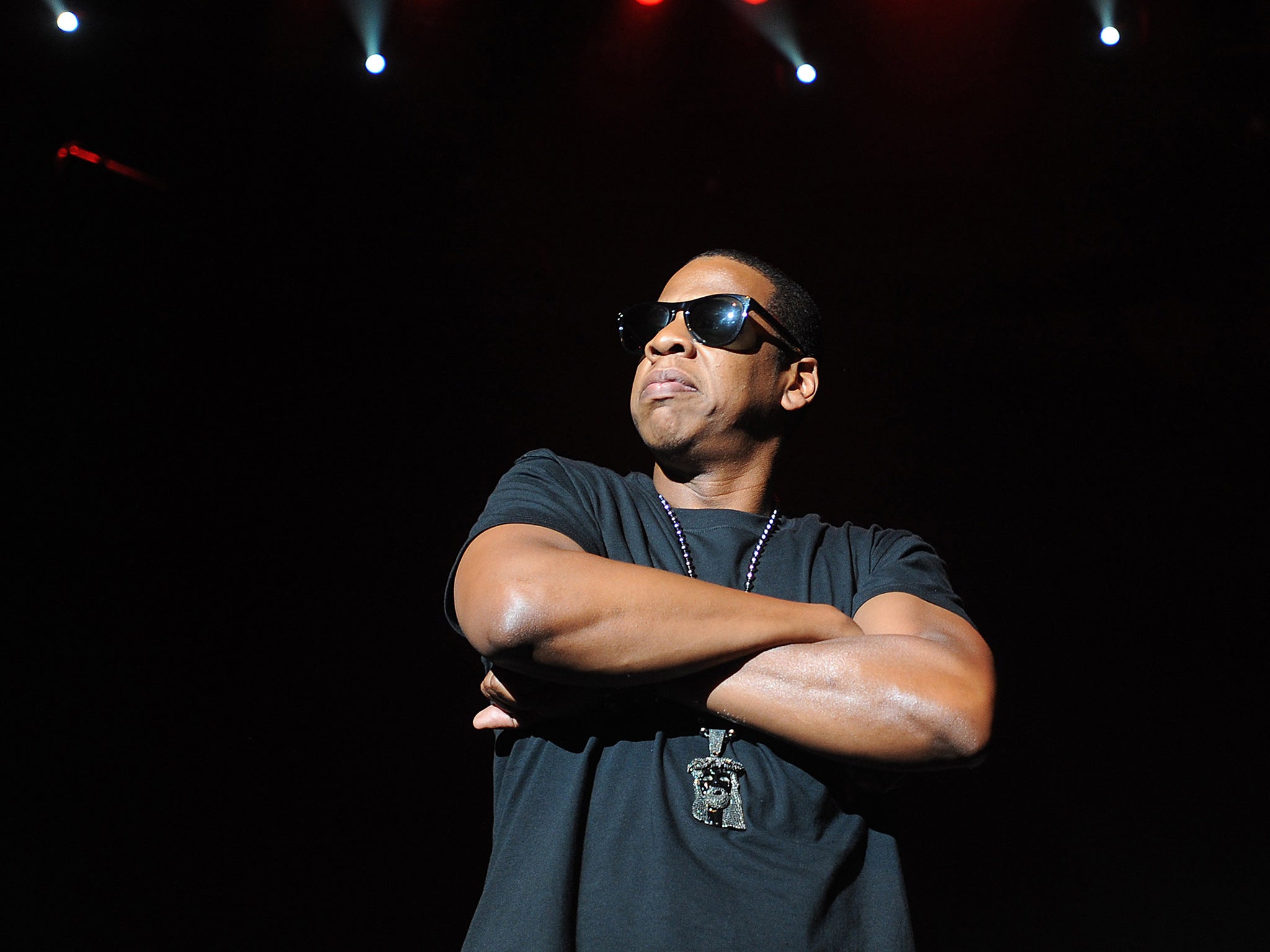

Big bets riding on a future of streaming

As Jay Z bids for Aspiro, Spotify raises cash and Amazon invests in video, Oscar Williams-Grut reports on the battle to sell online content

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When was the last time you bought a CD? Or a DVD? Chances are, if you are under 30 years old, it will have been a long time ago.

For a new generation of music listeners, TV viewers and film enthusiasts, streaming services such as Spotify and Netflix have replaced trips to HMV or even downloads from iTunes or Amazon. Streaming is infiltrating the mainstream much as satellite TV did 20 years ago,and the money men are taking note.

Spotify has reportedly hired Goldman Sachs to raise $500m (£330m) in fresh funding, valuing the business at $8bn. Goldman is already an investor. The Amazon founder, Jeff Bezos, revealed yesterday that the online retail giant has invested $1.3bn in the past year alone in its streaming service Prime Instant Video.

And even Jay Z, perhaps taking inspiration from fellow rapper-turned- entrepreneur Dr Dre, has got in on the act. He is bidding $56m for a Swedish streaming company, Aspiro. In 2015, streamers are set to step up the battle for our attention – and our cash.

“The main reason the money is going to streaming is consumers want it,” says Ian Maude, who studies online media for Enders Analysis. “The growth rate for Spotify now is just unbelievable. They announced 12.5 million paid subscribers at the end of November and now they’ve got 15 million.”

Mr Maude points to similar momentum at other streaming services such as Netflix, Prime Instant Video and NowTV.

“In the UK, we’ve dropped from 98 per cent TV in households to 96 per cent in just the last year,” says Maria Ingold, who runs the video-on- demand consultancy Mireality. “Tablet ownership is up from 29 per cent to 46 per cent. For kids especially, their TV experience is on a tablet.”

Technology underpins the rise of streaming, with more portable devices and faster internet making it a viable option. Ms Ingold was formerly the chief technology officer of the video-on-demand business FilmFlex and points out: “We started 18 years ago doing video on demand. But with the advent of cheaper faster broadband and 3G and 4G services, a lot of the traditional ways of consuming content have changed.”

For the creatives whose “content” underpins streaming services, the transition to this new distribution model has in some cases been hard.

In film and television, streaming has bought new inflows of cash. Both Amazon and Netflix have commissioned original series, with Amazon announcing recently that it has signed up Woody Allen to produce his first-ever TV series exclusively for Prime Instant Video.

But for the music industry, the rise of platforms such as Spotify, Rdio and Deezer has led to a shaving of the already meagre earnings of artists. Musicians complained of the $0.99 per track price enforced by Apple at the onset of iTunes, but that now seems princely next to the average $0.007 per stream royalty paid to artists by Spotify.

It may be scant consolation, but music streaming services themselves are struggling to make much money. Spotify, the sector leader, made a loss of €57.8m (£43.5m) last year. Oleg Fomenko, who ran the music streaming application Bloom.fm until it closed last year, believes this is a trivial detail, with Spotify focusing on growth rather than profit. “The last man standing will be making money,” he says. “Right now it’s just a rush for that scale.”

Bloom.fm was one of the many Spotify rivals that was crushed in the race for scale. It folded after its Russian backer pulled funding last year. “Blinkbox and Sony’s Music Unlimited closing down shows that unless you have got deep pockets, it is extremely difficult,” says Mr Maude. “Investors are increasingly willing to throw the towel in relatively quickly if something isn’t getting traction.”

Apple is expected to direct its deep pockets towards music streaming this year, having been caught short by the transition from downloads. The company spent $3bn on the Dr Dre headphone maker Beats last year and many analysts believe the deal was driven by the Beats music-streaming operation. Apple is tipped to relaunch the service soon, with the acquisition of the UK music analytics start-up Semetric thought to be part of this plan. “If Beats is pre-installed on a lot of Apple devices and it’s the default music service, then it could get a lot of traction,” says Mr Maude.

But the iPhone maker faces an uphill battle, with 60 million people around the world already signed up to Spotify. Mr Fomenko says: “I think we are going to have a similar situation to iTunes and Amazon. There is an 80 per cent player and then there are some far, far, far seconds. That is certainly what we’re going to see in music. In video streaming? I don’t know. The economics are quite a lot better.”

Netflix, the market leader, reported that it made a $65m profit in just the final three months of 2014. But this success has raised hackles elsewhere. Internet providers, whose technological advances enabled the streaming revolution, are demanding a share of the action.

“A third of the download traffic in the US is Netflix, which is why there are all of these fights going on about net neutrality,” explains Ms Ingold. “The internet service providers want to be able to get money from people like Netflix for taking up all of their traffic. But people like Netflix are also the reason why you want faster broadband. It’s a Catch-22 situation.”

Despite questions over profitability and industry levies, the sector shows no signs of slowing. Investors seem more than willing to plough money into streaming and the appetite among consumers has yet to be satisfied.

“Young people right now, for them ownership is actually onerous,” says Mr Fomenko. “If you look at Uber, people are using it not just instead of taxis but instead of their own car. Airbnb, it is the same. Things are moving that way in multiple areas – not just in digital content.”

The streamers: Going with the flow

Aspiro

The Swedish company owns the WiMP and Tidal streaming services. The latter is marketed as a higher- fidelity service than Spotify, Rdio and Deezer and charges a premium price of $20 a month.

Spotify

The Swedish company, founded in 2008, has around 60 million users and 15 million subscribers worldwide. The singer Taylor Swift removed her back catalogue from the site last year, complaining of the low royalties paid to artists.

Beats

Bought by Apple last May for $3bn, the largest purchase in the tech giant’s history. But Apple has not made any further indications of how Beats’ online music streaming service will be integrated into the product line. Competes with Apple’s own iTunes Radio service.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments