Are shiny new football stadiums a game-changer for communities?

Bigger stadiums mean more matchday revenues – and the spin-offs can benefit whole areas, say clubs anxious to keep councils and residents onside with their expansion projects

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

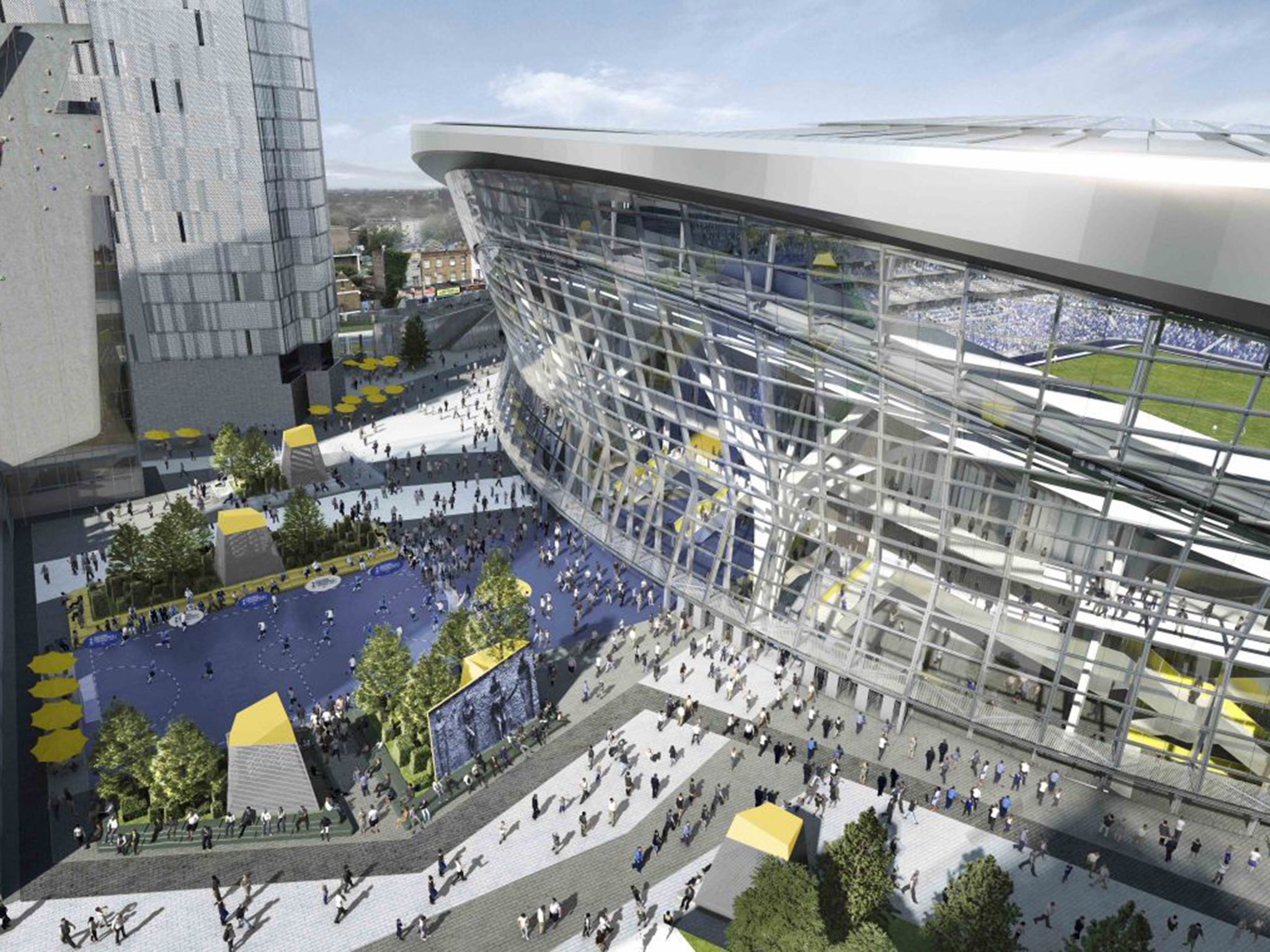

Your support makes all the difference.It is easy to imagine that management at the north London football club Spurs were chanting “Glory, Glory, Tottenham Hotspur” in the boardroom last week. The Premier League club has just got the green light for a major new £400m stadium after a “long and often difficult path”, that included years of planning to get the local authority and public on-side.

Spurs, which moved to White Hart Lane in 1899, is the latest in a series of British football clubs playing the regeneration game.

They have to convince councils that their new stadium can act as a catalyst for drastically improving an area, through the knock-on impact of creating jobs, increasing footfall and attracting private-sector investment. This stadium-led regeneration has emerged as a large-scale model over the last 15 years, a report by the London Assembly says.

The report certainly highlights that clubs stand to get a major financial boost from a new home ground. It notes that since moving to the Emirates Stadium in 2006, Arsenal’s annual match-day revenue has almost tripled, from £33.8m in 2004 to £100.2m in 2014.

Meanwhile, Brentford Football Club expects its planned new stadium to be worth £3m a year in extra revenue.

So while logic indicates that more seats and therefore more ticket sales can boost the coffers of football clubs, how much do football stadium redevelopments really help their towns and local economies? Are there any problems they create?

Queens Park Rangers’ chairman, Tony Fernandes, who also founded the budget airline AirAsia, told The Independent: “A QPR stadium at Old Oak [in west London] would not only create jobs and accelerate the delivery of housing, it would provide a beating heart for the regeneration.

“Places with a buzz become attractive areas to live, work and play, and that is what a multifunctional stadium with community, sports and educational facilities would provide.”

Tottenham Hotspur meanwhile is convinced that upsizing from a 36,284-seat to a 61,000-seater stadium, with a retractable pitch that allows Premier League and American Football games to be played and broadcast, will help to transform a part of London that is sometimes dubbed as run-down and has twice famously been blighted by riots.

Spurs’ plans include a hotel and nearly 600 homes. Some people have argued that they want to see more details on how much will be affordable, but the club and council are still ironing out the affordable housing element to make sure the scheme is viable.

Other areas to see a housing supply boost as a result of stadium regeneration include the north London home of Arsenal, and east Manchester.

The latter has been helped by Premier League side Manchester City. Just last year a deal was struck that could see over 6,000 new homes built in once rundown parts of Manchester thanks to a £1bn agreement between the council and the club’s Middle East owners. It was part of a commitment made by the club to invest in the area.

Its Etihad stadium was originally built for the Commonwealth Games in 2002. Since then the club “has been at the heart of the ongoing regeneration of east Manchester”, a spokesman for Manchester’s city council says.

And in the capital, Arsenal’s plans created 3,000 new homes, of which 40 per cent were affordable.

But the impact on residential property can be a double-edged sword for local residients, said Gabriel Ahlfeldt, associate professor of urban economics at the London School of Economics.

Professor Ahlfeldt said: “Homeowners get an amenity for free and will likely be able to sell their properties at a higher price should they ever leave the area. Renters, however, will likely have to pay a price for the amenity in the form of a higher rent.”

He continued: “For some renters, this price may well exceed the perceived benefits from the stadium. Possibly, those will look for a cheaper neighbourhood elsewhere.”

As well as the real estate market, clubs normally argue that stadium regeneration can help the local economy, and Haringey council’s leader, Claire Kober, agrees.

She said: “These proposals are about more than just a new stadium – they bring much-needed new jobs and a boost to the economy, with thousands more fans spending money in local businesses.”

Other clubs aiming to help employment include West Ham United, which expects to create 720 jobs at the Olympic stadium.

The east London side also attracted praise this year after it agreed to start paying the London Living Wage of £9.15 an hour to all permanent full-time and part-time staff from June.

But not everybody is convinced that new stadiums are good for business. Dave Morris, of the campaign group One Tottenham, says he is concerned that the plans for Tottenham “mean massive overdevelopment”, adding that some businesses are under threat from demolition to pave the way for the project.

The London Assembly’s report also makes reference to some community groups which argue that big-name companies moving to an area on the back of a new stadium “will squeeze out local, independent businesses”.

Professor Ahlfeldt also points out that “there are obvious disamenity effects during the construction period”.

But the fact that football club owners typically finance their own schemes cannot go unnoticed.

In an economic climate where councils are carefully watching budgets, football clubs are perceived as a great way to inject finance into a borough. It is unlikely that councils will want to show the red card to stadium plans that could attract mass investment to their areas.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments