The story so far: AP's investigation into federal prisons

An ongoing Associated Press investigation has uncovered deep, previously unreported flaws within the Justice Department’s largest law enforcement agency, the federal Bureau of Prisons

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

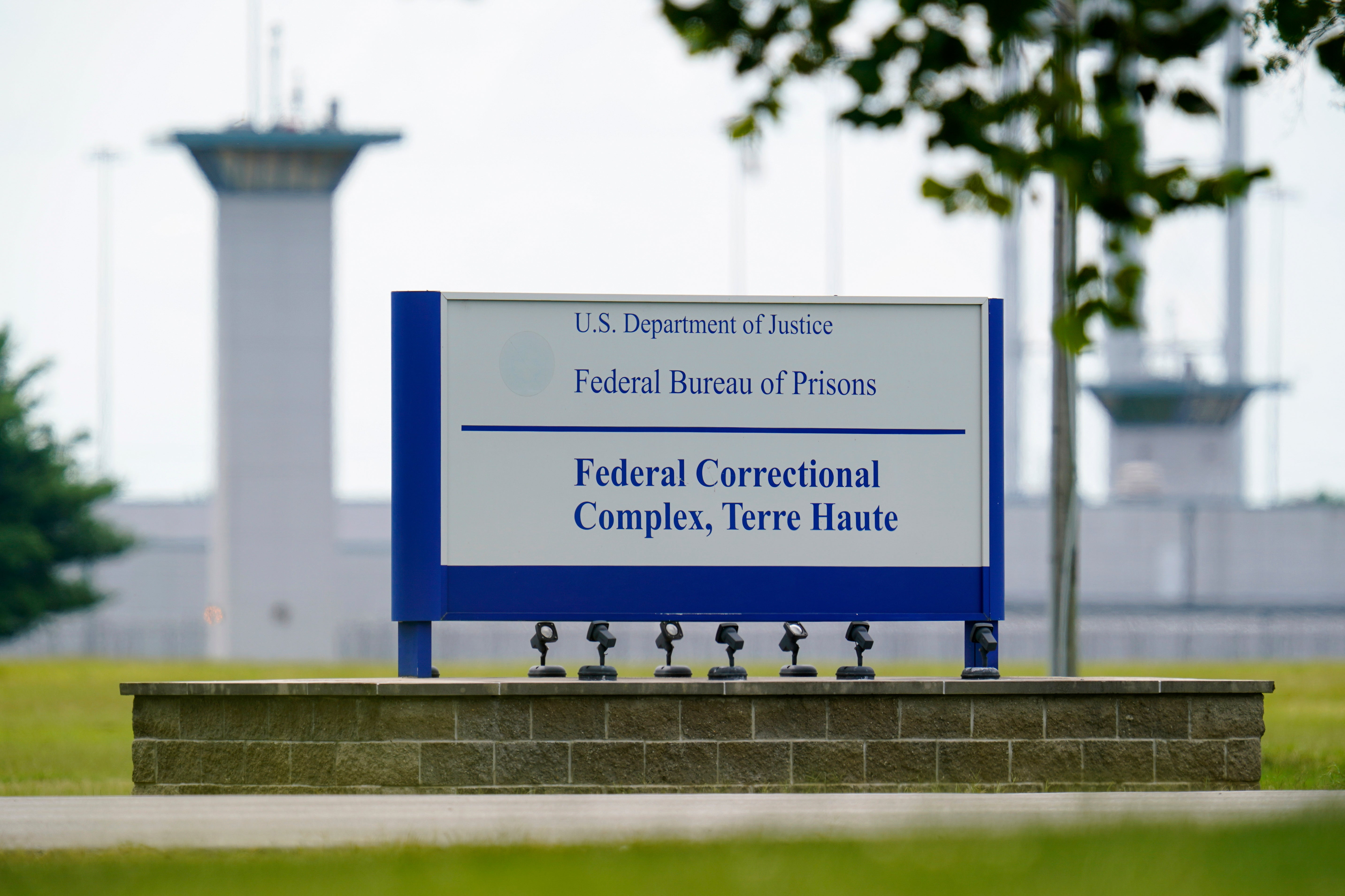

Your support makes all the difference.An ongoing Associated Press investigation has uncovered deep, previously unreported flaws within the federal Bureau of Prisons, the Justice Department’s largest law enforcement agency, whose secrets have long been hidden within its walls and barbed-wire fences.

The AP’s reporting has revealed layer after layer of abuse, neglect and leadership missteps — including rampant sexual abuse by workers, severe staffing shortages, inmate escapes and the mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic — leading directly to the agency’s director announcing his resignation earlier this year.

Among the AP’s findings, so far:

— Mess up, move up: A high-ranking official repeatedly promoted despite numerous red flags, including allegations that he beat inmates in the mid-1990s while a member of a violent, racist gang of guards called “The Cowboys.”

— Sexual abuse: A permissive, toxic culture of predatory employees at a women’s prison in California, fueled by cover-ups that largely kept their misconduct out of the public eye for years. Among the accused is the prison’s former warden.

— Criminal misconduct: More than 100 Bureau of Prisons workers arrested, convicted or sentenced for crimes since the start of 2019, but the agency has turned a blind eye to employees accused of misconduct, in some cases failing to suspend them after their arrests.

— Staffing crisis: Nearly one-third of federal correctional officer positions vacant, forcing prisons to use cooks, teachers, nurses and other workers to guard inmates, hampering the response to emergencies, including inmate suicides.

— Escaping inmates: 29 prisoners escaped from federal prisons in an 18-month span, with nearly half still at large. At some institutions, doors are left unlocked, security cameras are broken and officials sometimes don’t notice an inmate is missing for hours.

— Superspreader executions: An unprecedented string of federal executions likely acted as COVID-19 superspreader events, just as health experts warned could happen when the Trump administration insisted on resuming executions during a pandemic.

— Crumbling infrastructure: A rare look inside the Metropolitan Correctional Center, the federal jail in Manhattan where Jeffrey Epstein died, revealed squalid, unsafe conditions including falling concrete, freezing cold temperatures, busted cells and broken pipes.

AP writers Michael Balsamo and Michael Sisak started digging into the Bureau of Prisons after Epstein’s 2019 suicide. At first, they wanted to understand how the highest-profile federal inmate in decades was able to take his own life.

As they continued reporting, it became clear that the dysfunction surrounding Epstein's suicide — guards sleeping and browsing the internet, one of them pulled from a different prison job to watch inmates, both working overtime shifts — wasn't a one off but a symptom of a federal prison system in deep crisis.

The AP's exclusive reporting has forced lawmakers to take notice.

Sen. Jon Ossoff, D-Ga., introduced legislation that would require the Bureau of Prisons to fix broken cameras. Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, went to the Senate floor and read AP stories into into the congressional record as he demanded Attorney General Merrick Garland fire the agency’s director, Michael Carvajal.

A few weeks later, Balsamo and Sisak broke the news that Carvajal, a Trump administration holdover, and his top deputy were resigning.

These stories aren’t possible without the help of whistleblowers, inmates and their families, and anyone else who suspects wrongdoing or knows what’s going on and tells us about it.

There are several ways you can share your stories and tips with the AP:

— Visit https://ap.org/tips for instructions on how to share information confidentially and securely.

— Email AP writers Michael Balsamo at mbalsamo@ap.org and Michael Sisak at msisak@ap.org.