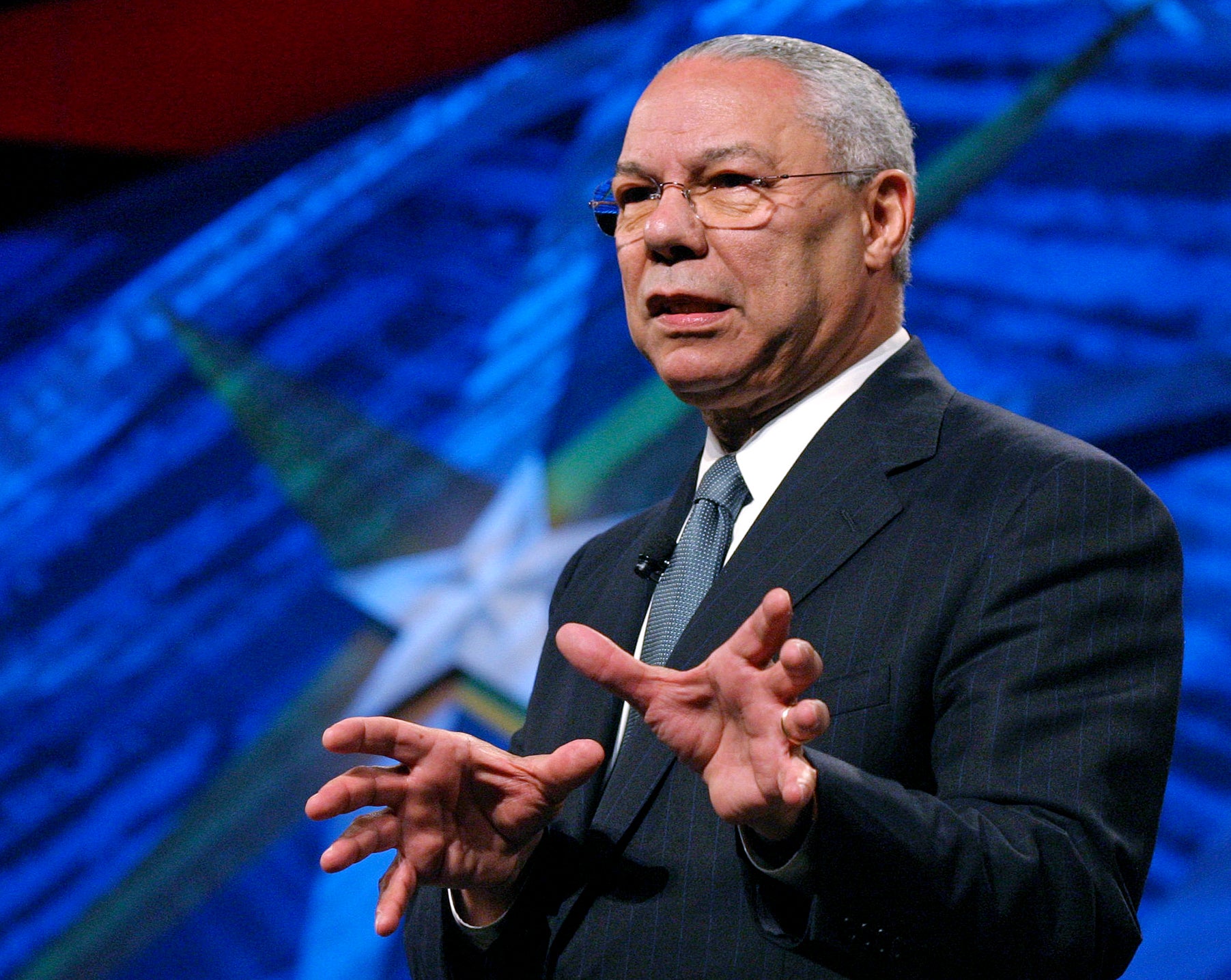

Memorial service in honor of Colin Powell set for Nov. 5

A memorial service for Colin L

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A memorial service for Colin L. Powell, the retired Army general and former secretary of state who died on Monday, will be held Nov. 5 at Washington National Cathedral, a spokeswoman said Thursday.

“There will be very limited seating and it will be by invitation only,” Peggy Cifrino said in an emailed statement.

Powell died of complications from COVID-19 at age 84. He had been vaccinated, but his family said his immune system had been compromised by multiple myeloma, a blood cancer for which he had been undergoing treatment.

The retired Army general was widely praised as a pathbreaker, having been the first Black person to serve as U.S. secretary of state and as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He spent 35 years in uniform, and the story of his rise to prominence as a soldier and a diplomat was a historic example to minorities.

He joined President George W. Bush’s administration in 2001 as secretary of state. Powell’s tenure was marred by his February 2003 U.N. address in which he cited faulty information to claim that Iraq’s Saddam Hussein had secretly stashed weapons of mass destruction. Such weapons never materialized, and though the Iraqi leader was removed, the war devolved into years of military and humanitarian losses.

No child of privilege, Powell often framed his biography as an American success story.

“Mine is the story of a black kid of no early promise from an immigrant family of limited means who was raised in the South Bronx,” he wrote in his 1995 autobiography, “My American Journey.”

It’s an experience he was fond of recalling later in his life. When he appeared at the United Nations, even during his Iraq speech, he often reminisced about his childhood in New York City where he grew up the child of Jamaican immigrants and got one of his first jobs at the Pepsi-Cola bottling plant directly across the East River from the U.N. headquarters.

Powell’s path toward the military began at City College, where he discovered the ROTC. When he put on his first uniform, he wrote, “I liked what I saw.”

He joined the Army and in 1962 was one of more than 16,000 military advisers sent to South Vietnam by President John F. Kennedy. A series of promotions led to the Pentagon and assignment as a military assistant to Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger. He later became commander of the Army’s 5th Corps in Germany and was national security assistant to President Ronald Reagan

During his term as Joint Chiefs chairman, which started in 1989, his approach to war became known as the Powell Doctrine, which held that the United States should only commit forces in a conflict if it has clear and achievable objectives with public support, sufficient firepower and a strategy for ending the war.