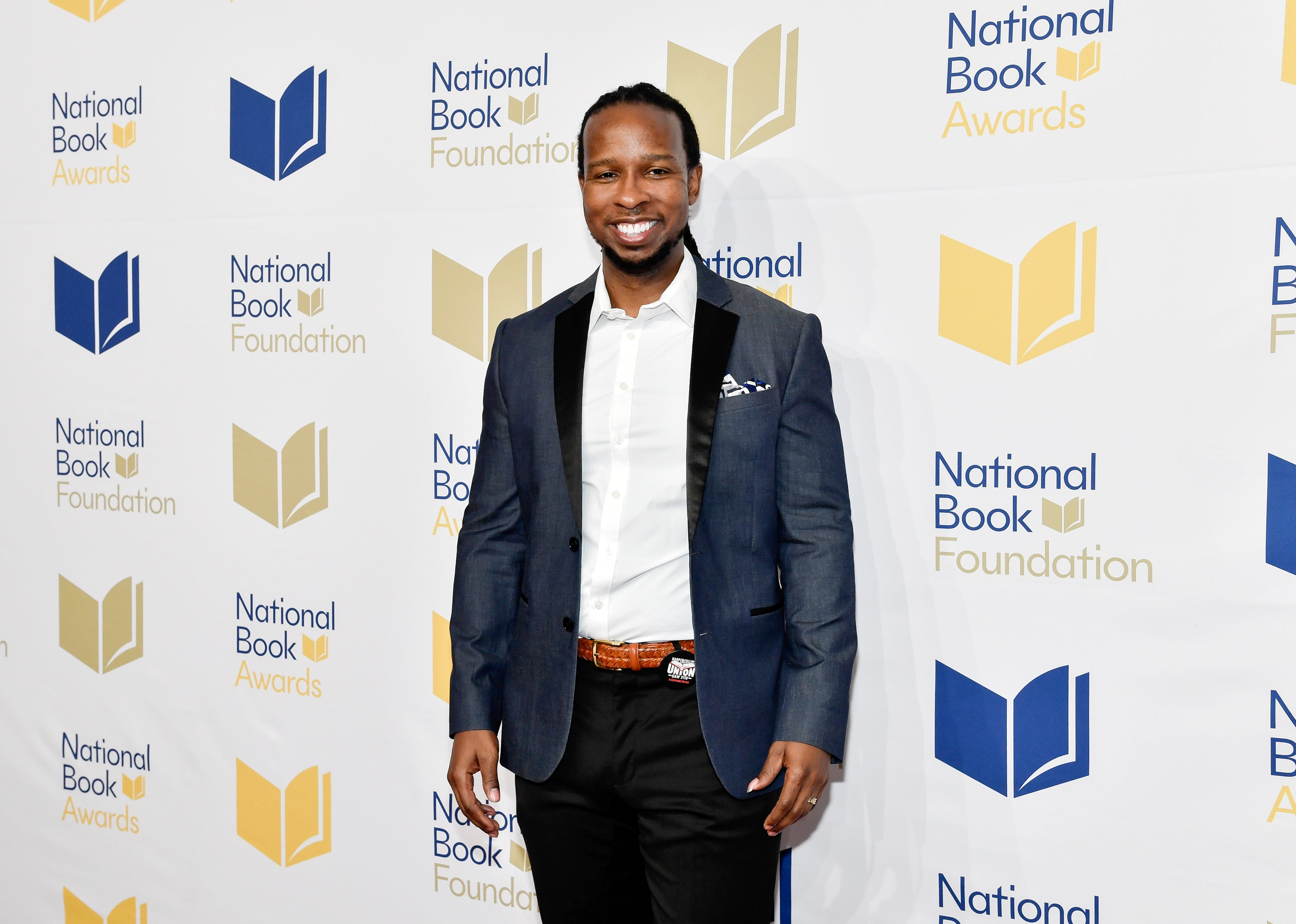

What should donors learn from Ibram X. Kendi’s problems at Boston University?

In September, the award-winning author and academic Ibram X

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The award-winning author and academic Ibram X. Kendi has been a lightning rod for public discourse since publishing his book “How to Be an Antiracist” in 2019. But in September, the praise and criticism reached new intensity when Boston University acknowledged layoffs at the center he runs there along with a change to its operating model.

The news prompted former colleagues and current collaborators to publicly question the BU Center for Antiracist Research's ability to deliver on the promises it had made to funders. In news reports and op-eds, some former colleagues said too much power was concentrated in Kendi’s hands. People and organizations that oppose racial equity piled on.

Earlier this month, the university said an initial inquiry found no issues with how the center managed its finances.

Acknowledging the layoffs in September, the university and Kendi said it was not financially sustainable to conduct research and develop programs with its own employees, despite having raised more than $50 million for the center since its founding in 2020. Instead, the center will host academics for nine-month fellowships. The center will no longer develop a Master’s program in antiracism studies curriculum, an academic minor for undergraduates or a database of antiracist campaigns across the U.S.

Despite the hubbub, essentially none of the center's funders have raised public concerns about its work. Grantmakers and advocates for racial justice within philanthropy said the center's problems don't represent a larger trend about donations made in 2020 around racial justice, especially given that it's not usual for new organizations to have growing pains.

Earl Lewis, a historian and former president of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, who now runs the University of Michigan Center for Social Solutions, said it was not at all unusual for a new leader and a new organization to confront the constraints of time and money and recalibrate their plans.

“It’s just fascinating to me that actually this became a national story in a certain kind of way, which begs the question of why?" he said, wondering if some were cheering for Kendi's vision to fail.

Kendi has acknowledged “missteps” during the center's first years, adding in a September statement that “New organizations often undergo a difficult evolution before landing on a successful model.”

In an interview with The Associated Press, Kendi pointed at the racist ideas that “Black people can’t manage money or Black people take money,” as the driver behind questions and doubts about the center’s management of its finances.

“Unfortunately, over the last three years, there have been all sorts of character assassinations of those of us who are engaged in antiracist work," he said. “There’s been all sorts of attacks on antiracist organizations or even programs that are trying to create equity and justice.”

His center is far from the only target of those attacks. The foundation that grew out of the Black Lives Matter movement faced similar questions and scrutiny after it revealed that it had raised tens of millions of dollars but operated for a time with weak governance. And the Supreme Court's decision in June to strike down affirmative action in college admissions continues has fueled attacks on diversity programs across sectors.

Lewis and others with experience in philanthropy and academia encouraged scrutiny of and accountability for the commitments made by corporations, foundations and other institutions in 2020 to support racial justice, but argued that the fate of Kendi's center is not a bellwether for the health of the larger movement.

Of the $50 million the center raised, $30 million is held in an endowment, the university said. It's a huge amount to have raised for a new institute, with donors ranging from corporations like Peleton and Stop & Shop, philanthropic mainstays like the Rockefeller Foundation, and high-profile individuals like Jack Dorsey. But it's not enough to support a staff of more than 40 as the center had before 19 people were laid off.

Going forward, the center will instead host research fellows, continue to publish its online publication, " The Emancipator," and host public events. Personally, Kendi recently had a new series on racism and sports launch on ESPN and a Netflix documentary based on “Stamped from the Beginning,” will premier on Nov. 20.

Chera Reid, co-executive director at the Center for Evaluation Innovation, which supports efforts in philanthropy to advance racial justice, said that despite the furor over the layoffs, she wasn't seeing any fallout ripple through the philanthropic ecosystem.

She cautioned that in examining the outcome of commitments made by philanthropic organizations in 2020, not to read too much into one example, because doing so, “flattens all of the progress that’s being made. It flattens all of the effort that’s underway.”

Reid pointed to the sold-out CHANGE Philanthropy Unity Summit, which convened in Los Angeles in October and brings together people working in philanthropy to make institutions and practices more equitable. She argued that many in the field continue to work to shape the legacy of the commitments made in 2020.

For example, the outgoing CEO of The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Larry Kramer, this summer described the foundation’s $150 million commitment to racial justice as a “ramp up,” meaning a path to build on. He was speaking to a group of outside advisors to the foundation, including Reid.

“What I would like to see is far more of philanthropy who says it cares about justice, who says its work is about our shared humanity, find their way to the ramp up. Tell us about the ramp up,” Reid said. "We don’t need to know that you know everything. But tell us how you’re going to puzzle through.”

The sudden termination of the center’s research projects prompted some within the movement for racial justice to see good reason to criticize Kendi’s leadership.

Observers, like Jenn M. Jackson, assistant professor of political science at Syracuse University, argued that this episode reveals a mismatch between what funders in 2020 said they wanted to do, which was to end racist policies in the U.S., and the way they went about it, which was to give millions to a new research center at a university.

“There’s still no engagement with decolonization, with actually thinking about what would it mean if these funders started funding radical organizations who wanted to actually think about what it means to be free,” Jackson said, speaking in general about philanthropic donations.

Kendi agreed many funders were new to racial justice philanthropy in 2020, but said they didn’t usually give to his center. Kendi said most of the center's funders already supported antiracist community organizations. The AP could not independently confirm this since a complete list of the center's donors is not public.

For Reid, the philanthropic advisor, the argument about whether donors or nonprofits have lived up to their commitments for change isn't a useful way to spend energy.

“The longer we stay in this ‘2020, did we do it?’ The more we’re really fighting about the wrong things,” she said. “I want to hear us talk about and move in the possibility, not continue to admire the problem.”

___

Associated Press coverage of philanthropy and nonprofits receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content. For all of AP’s philanthropy coverage, visit https://apnews.com/hub/philanthropy.