A new strategy to attack aggressive brain cancer shrank tumors in two early tests

Researchers revved up immune cells that shrank an extremely aggressive type of brain tumor when tested in a handful of patients

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A new strategy to fight an extremely aggressive type of brain tumor showed promise in a pair of experiments with a handful of patients.

Scientists took patients’ own immune cells and turned them into “living drugs” able to recognize and attack glioblastoma. In the first-step tests, those cells shrank tumors at least temporarily, researchers reported Wednesday.

So-called CAR-T therapy already is used to fight blood-related cancers like leukemia but researchers have struggled to make it work for solid tumors. Now separate teams at Massachusetts General Hospital and the University of Pennsylvania are developing next-generation CAR-T versions designed to get past some of glioblastoma’s defenses.

“It’s very early days,” cautioned Penn’s Dr. Stephen Bagley, who led one of the studies. But “we’re optimistic that we’ve got something to build on here, a real foundation.”

Glioblastoma, the brain cancer that killed President Joe Biden’s son Beau Biden and longtime Arizona Sen. John McCain, is fast-growing and hard to treat. Patients usually live 12 to 18 months after diagnosis. Despite decades of research, there are few options when it returns after surgery and radiation.

The immune system's T cells fight disease but cancer has ways to hide. With CAR-T therapy, doctors genetically modify a patient’s own T cells so they can better find specific cancer cells. Still, solid tumors like glioblastoma offer an additional hurdle — they contain mixtures of cancer cells with different mutations. Targeting just one type allows the rest to keep growing.

Mass General and Penn each developed two-pronged approaches and tried them in patients whose tumors returned after standard treatment.

At Mass General, Dr. Marcela Maus’ lab combined CAR-T with what are called T-cell engaging antibody molecules — molecules that can attract nearby, regular T cells to join in the cancer attack. The result, dubbed CAR-TEAM, targets versions of a protein called EGFR that’s found in most glioblastomas but not normal brain tissue.

Penn’s approach was to create “dual-target” CAR-T therapy that hunts for both that EGFR protein plus a second protein found in many glioblastomas.

Both teams infused the treatment through a catheter into the fluid that bathes the brain.

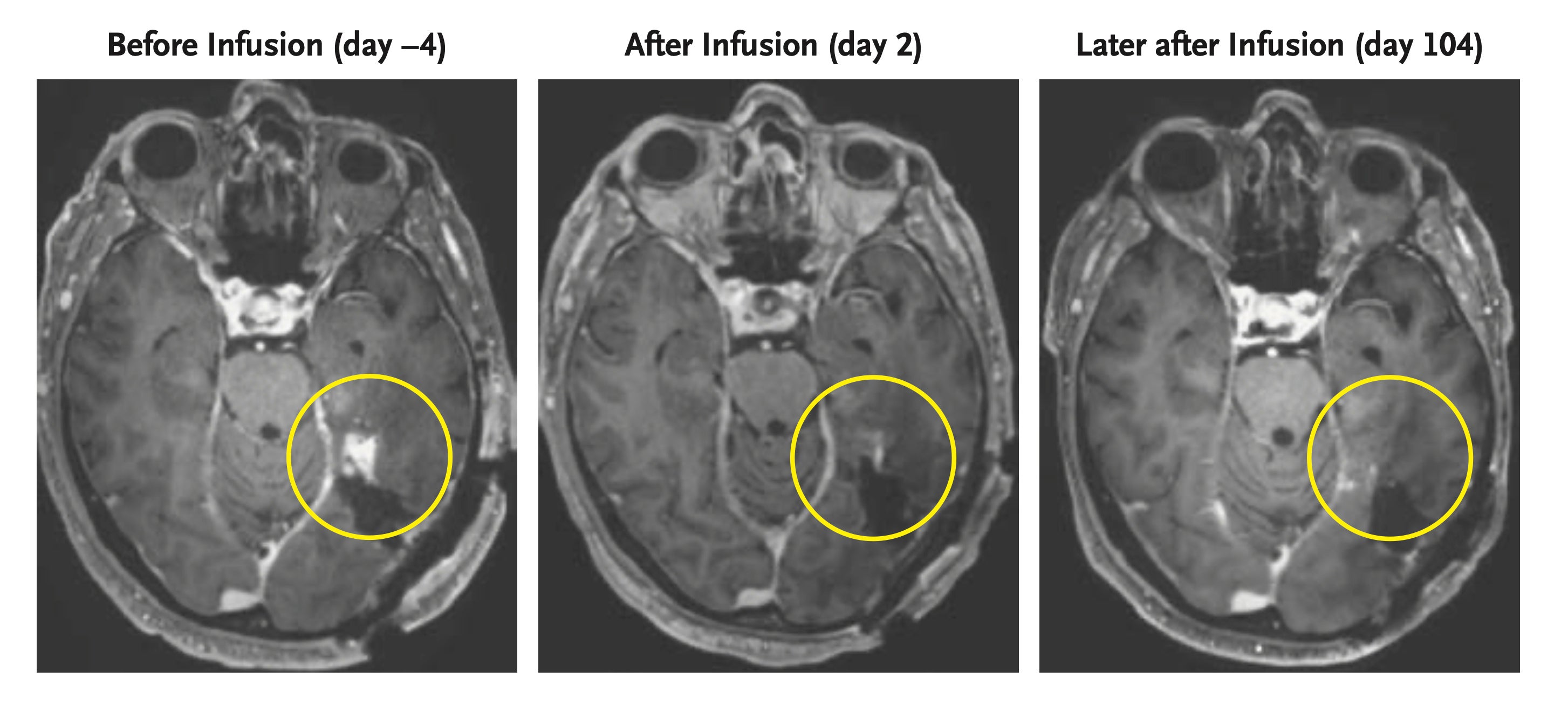

Mass General tested three patients with its CAR-TEAM and brain scans a day or two later showed their tumors rapidly began shrinking, the researchers reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“None of us could really believe it,” Maus said. “That doesn’t happen.”

Two of the patients' tumors began to regrow soon and a repeat dose given to one of them didn’t work. But one patient’s response to the experimental treatment lasted more than six months.

Similarly, Penn researchers reported in Nature Medicine that the first six patients given its therapy experienced varying degrees of tumor shrinkage. While some rapidly relapsed, Bagley said one treated in August so far hasn't seen regrowth.

For both teams, the challenge is to make it longer-lasting.

“None of this is going to matter if it doesn't last,” Bagley said.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.