Why is France trying top Syrian former officials for alleged torture and killing of father and son?

In a landmark trial, a Paris court will this week seek to determine whether top Syrian intelligence officials were responsible for the disappearance and deaths of a French-Syrian father and his son

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Syrian soldiers came first, at night, for the son, Patrick, a 20-year-old psychology student at Damascus University, and said they were taking him away for questioning.

They came back the next night for his father, Mazen.

Five years later, in 2018, death certificates from Syrian authorities confirmed to the Dabbagh family that the French-Syrian father and son would never come home again.

In a landmark trial, a Paris court will this week seek to determine whether Syrian intelligence officials — the most senior to go on trial in a European court over crimes allegedly committed during the country's civil war — were responsible for their disappearance and deaths.

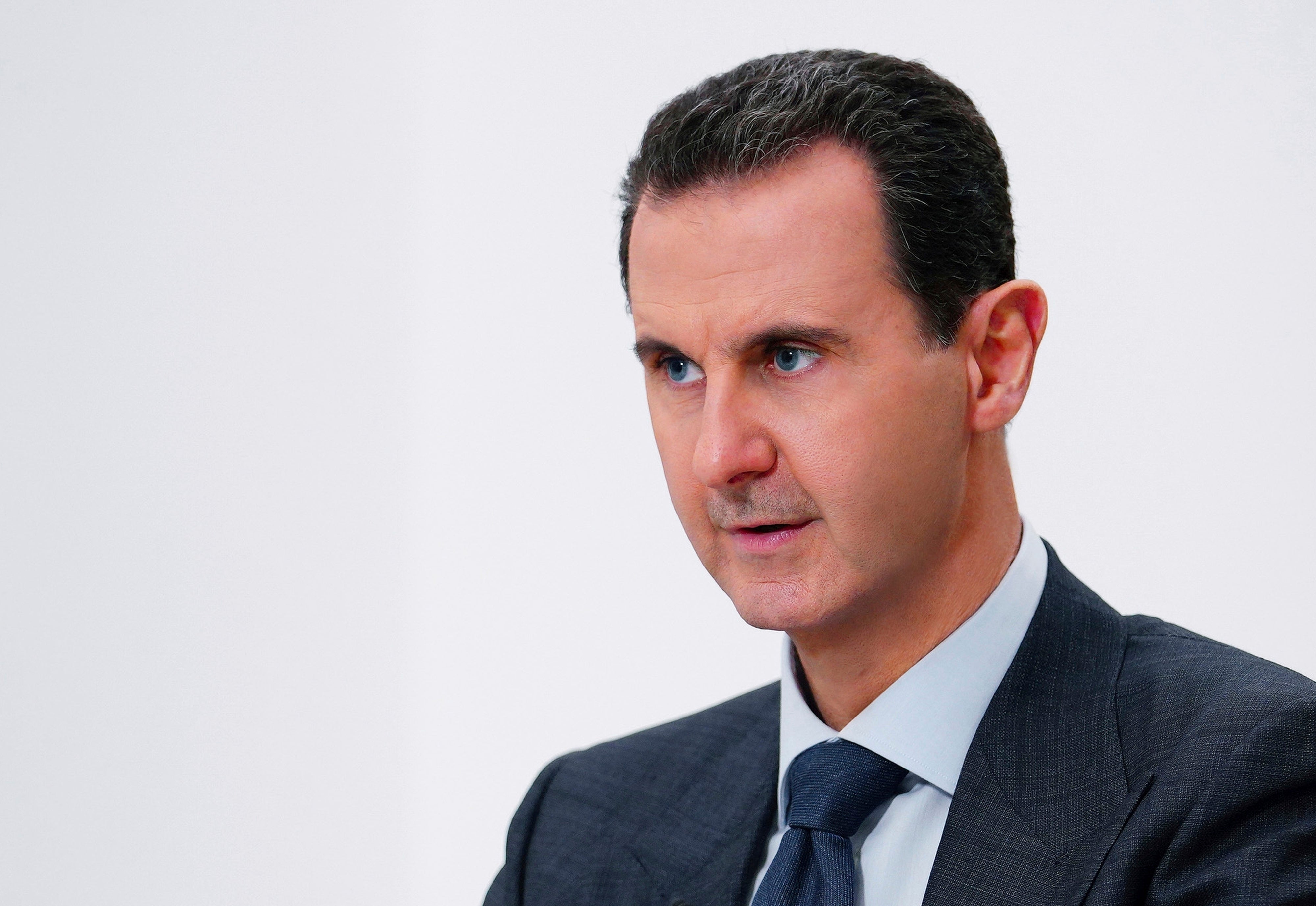

The four-day hearings from Tuesday are expected to air chilling allegations that President Bashar Assad's government has widely used torture and arbitrary detentions to keep power during the conflict, now in its 14th year.

The French trial comes as Assad has been regaining an aura of international respectability, starting to shed his long-time status as a pariah that flowed from the violence unleashed on his opponents. Human rights groups that are parties to the French case hope it will refocus attention on alleged atrocities.

Here's a look at those involved:

THE ACCUSED

Ali Mamlouk, former head of the National Security Bureau overseeing Syrian security and intelligence services. Allegedly worked directly with Assad. Now in his late 70s.

Jamil Hassan, former Air Force intelligence director. Survivors testifying in the case allege having seen him at a detention center in the capital, Damascus, where the Dabbaghs are thought to have been held. In his early 70s.

Salam Mahmoud, in his mid-60s, a former investigations official at a Damascus military airport believed to house the detention center. Mahmoud is alleged to have expropriated the Dabbaghs' house after they were taken away.

The three men are accused of provoking crimes against humanity, giving instructions to commit them and allowing subordinates to commit them through the alleged arrest, torture and killing of the father and son. They also are accused of confiscating their house and of putting Air Force intelligence services at the disposal of people who allegedly killed them.

The accused are being tried in absentia. French magistrates issued arrest warrants for them in October 2018, despite acknowledging that there was little likelihood of their extradition to France. Defense lawyers will not represent them and French magistrates determined they don't have diplomatic immunity.

“The three people accused are very senior officials of the Syrian system of repression and torture. This gives a particular tone to this trial. They are not small fish,” said Patrick Baudouin, a lawyer for rights groups involved in the case.

“The legal file is very detailed, full of evidence of systematic, very diverse and absolutely monstrous torture practices," Baudouin said.

WHY IS THE TRIAL IN FRANCE?

Patrick and Mazen Dabbagh had dual French-Syrian nationality, which enabled French magistrates to pursue the case. The probe of their disappearance started in 2015 when Obeida Dabbagh, Mazen's brother, testified to investigators already examining war crimes in Syria.

Obeida Dabbagh lives in France with his wife, Hanane, and is also a party in the case. According to the trial indictment, seen by The Associated Press, he told French investigators that three or four soldiers came for Patrick around 11 p.m. on Nov. 3, 2013, during the height of Arab Spring-inspired anti-government protests that were met by a brutal crackdown. The soldiers identified themselves as members of a Syrian Air Force intelligence branch. Obeida also testified they searched the house, taking cellphones, computers and money.

They came back the next night for Mazen Dabbagh, who was 54 and worked as a counselor at a French high school in Damascus, and also took his new car, the brother said.

Their death certificates said Patrick died Jan. 21, 2014, and Mazen on Nov. 25, 2017, but didn't say how or where.

THE TRIAL EXPECTED TO EXPOSE TORTURE

French investigating magistrates collected evidence from Syrian regime deserters and prison survivors as they built the case.

Testifying anonymously, survivors' accounts speak in the indictment of rape and of being denied food and water, of beatings on feet, knees and elsewhere with whips, cables and truncheons, of electric shocks and burnings with acid or boiling water, of being suspended from the ceiling for hours or days.

Investigators also studied images provided by a Syrian policeman, who anonymously turned over photographs of thousands of torture victims.

Cameras are generally banned from French criminal trials, but this one will be filmed for the historical record.

ANOTHER FRENCH PROBE TARGETS PRESIDENT ASSAD

In a separate investigation, French magistrates have also targeted President Assad himself but face questions about whether he benefits from presidential immunity.

Magistrates are investigating chemical weapons' attacks that killed more than 1,000 people and injured thousands of others in the suburbs of Damascus in 2013. They issued international arrest warrants for Assad, his brother Maher Assad, commander of the 4th Armored Division, and two Syrian army generals — Ghassan Abbas and Bassam al-Hassan — for alleged complicity in war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The French probe was opened in 2021 in response to a criminal complaint by attack survivors. The investigation is being conducted under the principle of universal jurisdiction, which argues that in some cases, crimes can be pursued outside the countries where they take place.

The Syrian government and its allies denied responsibility for the attacks.

The French warrants, very rare for a serving world leader, were seen as a strong signal against President Assad’s leadership at a time when some countries have welcomed him back into the diplomatic fold. Victims' lawyers hailed the warrants as “a crucial milestone in the battle against impunity.”

The Paris appeals court is weighing whether Assad has absolute immunity as head of state. French prosecutors asked it to rule on that question at a closed hearing May 15.

That procedure does not impact the warrants for Assad’s brother and the generals.

OTHER COUNTRIES ALSO TAKING ACTION

In March, Swiss prosecutors indicted Rifat Assad, the president’s uncle and a former Syrian vice president, for allegedly ordering murder and torture more than four decades ago to crush a Muslim Brotherhood uprising in the city of Hama where thousands were killed.

A court in Stockholm put a former Syrian army general who lives in Sweden on trial in April for his alleged role in war crimes in 2012.

Courts in Germany found two former Syrian soldiers guilty in 2021 and 2022 of crimes against humanity. One was sentenced to life imprisonment, the other to 4 1/2 years for complicity. They had claimed refugee status in Germany before former detainees recognized them. They were tried under the principle of universal jurisdiction.

___

Barbara Surk reported from Nice, France. Associated Press writer Kareem Chehayeb in Beirut contributed to this report.