Teen: Arkansas trans care law could force him to uproot life

An Arkansas teenager who is receiving hormone therapy says a state ban on such treatments could force he and his family to leave the sate

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

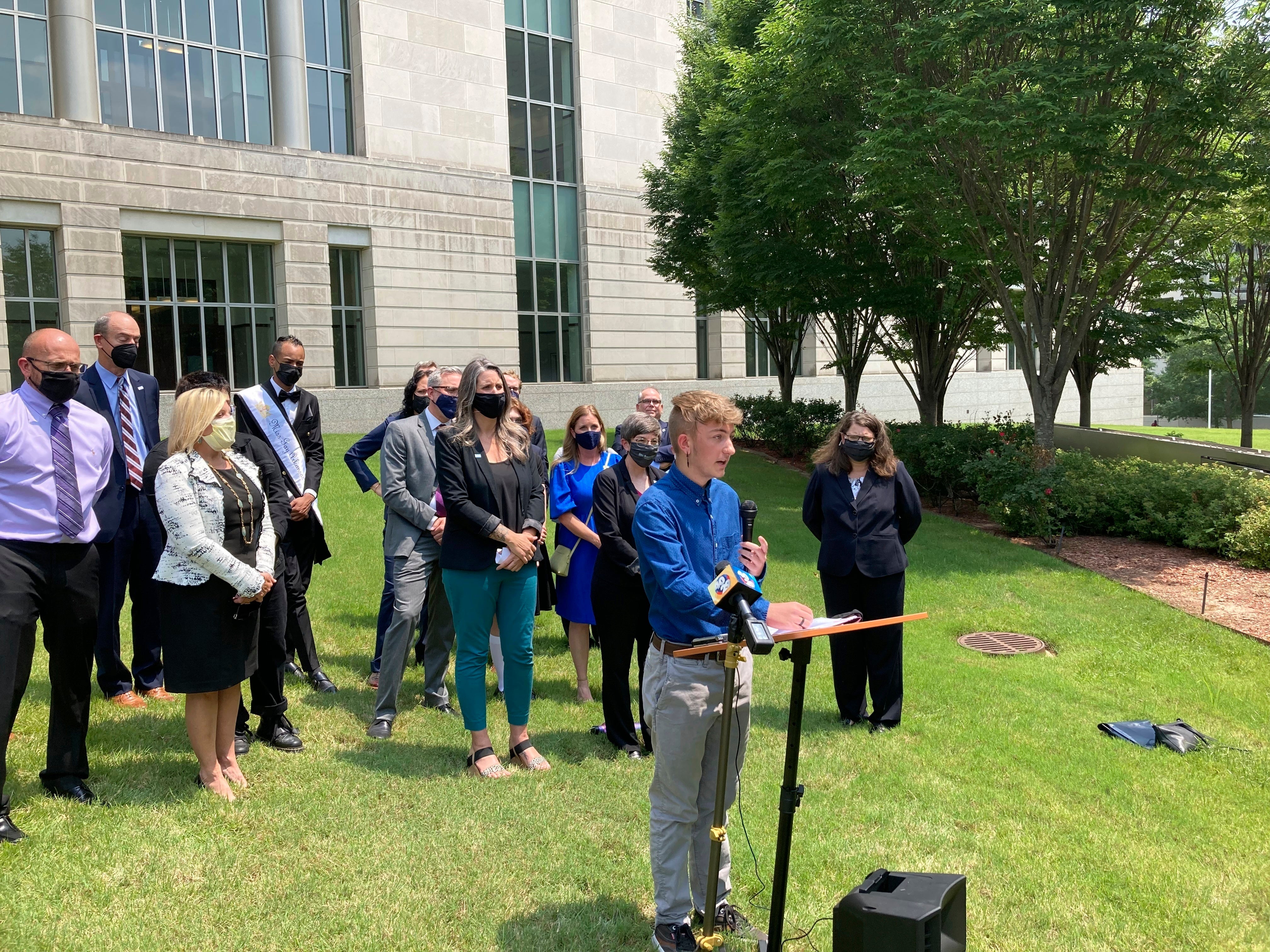

Your support makes all the difference.Testifying at the nation's first trial over a state ban on gender affirming care for children, 17-year-old Dylan Brandt said Wednesday that his life has been transformed by the hormone therapy he's receiving and banning the treatment in Arkansas could force his family to leave.

Brandt, his mother and the mother of another transgender child were among the final witnesses as opponents of Arkansas' law wrapped up their case in federal court. Brandt and his mother said their family may have to move from their home in west Arkansas to another state if the law is upheld.

“It would mean uprooting our entire lives, everything that we have here," Brandt said.

U.S. District Judge Jay Moody, who is hearing the case, last year temporarily blocked the law, which would prohibit doctors from providing gender-affirming hormone treatment, puberty blockers or surgery to anyone under 18 years old. It also would prevent doctors from referring patients elsewhere for such care.

Brandt, one of four transgender minors challenging the law, said he began hormone therapy in August 2020 and described how the treatments have made him happier and more comfortable about having his picture taken.

“My outside finally matches the way I feel on the inside," he said. “I have my days, but for the most part this has changed my life for the better. I can look in the mirror and be OK with the way I look and it feels pretty great."

Amanda Dennis, whose 10-year-old transgender daughter would be unable to begin receiving gender affirming care if the law takes effect, said her family is also looking at possibly moving or having to travel out of state for treatment.

“I've always promised all of our children we will care for you and do what is necessary to allow you to grow and live a happy life," Dennis said, her voice shaking. “The fact that I can't or potentially will not be able to get care for one of my children, it fills me with such sorrow that that would happen here where I live."

Arkansas was the first state to enact such a ban on gender affirming care, with Republican lawmakers in 2021 overriding GOP Gov. Asa Hutchinson’s veto of the legislation. Hutchinson, who had signed other restrictions on transgender youths into law, said the prohibition went too far by cutting off the care for those currently receiving it.

A similar ban has been blocked by a federal judge in Alabama.

The state has argued that the prohibition is within its authority to regulate the medical profession. People opposed to such treatments for children argue they are too young to make such decisions about their futures.

Multiple medical groups, including the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, oppose the bans and experts say the treatments are safe if properly administered.

The current and former medical directors of the Gender Spectrum Clinic at Arkansas Children’s Hospital testified that the hospital in February changed its policy and stopped prescribing puberty blockers and hormone therapy to new patients. The clinic’s patients who were already on the medications continue to receive the treatment.

Dr. Kathryn Stambough, the clinic's current medical director, said there are 81 patients still receiving hormone therapy. Dr. Michele Hutchison, the clinic's former medical director, said a letter the hospital sent to families about the change cited concerns that the state law might take effect in the near future.

Hutchison said she fears what will happen to patients if Arkansas' ban does go forward.

“My fear is that a lot of these patients will find ways to get these medications and they'll be doing so without the care of a physician," she said. “Secondly, and not to sound crass, but I'm genuinely worried we're going to lose some kids."

The state is expected to call three witnesses on Friday, with the trial set to continue in late November or early December.

A three-judge panel of the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in August upheld Moody’s preliminary injunction blocking the ban’s enforcement. But the state has asked the full 8th Circuit appeals court to review the case.