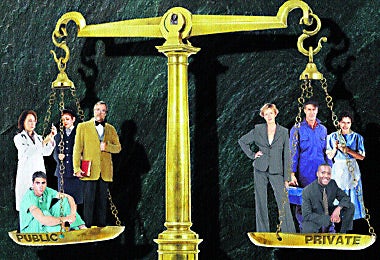

Is it time to say goodbye to a life in the public sector?

Public sector staff are seething - but is the private sector any better?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What's going on in Britain's public sector? Whether it's schools, universities, the health service or local government, staff seem to be miserable, with a marked increase in industrial action and other protests in recent months. While public sector staff were once happy to put up with the downsides of their jobs, in many areas staff now seem just as angry as those in the private sector.

Last month, more than a million local government workers staged a strike over cuts to the value of their pensions, and university lectures plan a protest next month in a bid for a better pay deal.

It's a similar tale in the health service. When the Health Secretary, Patricia Hewitt, told the Royal College of Nursing that the NHS had had its best-ever year, she was booed.

It wasn't always this way. For years, surveys of public sector workers showed much higher staff morale than in the private sector. Pay was considered lower, but pension and other benefits were more attractive, job security was better, and there was the feel-good factor of public service.

Strangely, while many public sector workers now seem more disgruntled, the evidence is that pay and conditions have improved in the past six years. According to the Chartered Institute of Professional Development (CIPD), the public sector workforce rose by almost 600,000 - 11 per cent - from 1998 to 2004, with many new jobs offering pay that, for the first time, was competitive with the private sector.

Has the social contract changed? It may be that, in return for higher pay, public sector workers have to put up with problems that have dogged those in the private sector for years. If so, where should those entering the workforce for the first time look for a job? And should staff already in work consider changing sides?

PAY

Working in the public sector has long been associated with lower wages, but now it's a myth that you can't earn good money outside the private sector. In terms of salary, at least, many workers are now on wages broadly comparable with private sector counterparts, though there is evidence that other benefits are being pared back.

According to the CIPD, the median salary in the public sector is now marginally higher than in the private sector, with many top management jobs paying in six figures.

In the early 1990s, public sector pay rises were capped at 1.5 per cent a year; a policy Chancellor Gordon Brown continued for another two years when he took over in 1997. But by 2000, this policy had been unwound, and public sector pay rises reached 5.1 per cent by 2003 - way ahead of the 3.7 per cent private sector average.

"We're in the middle of the biggest public sector pay reform agenda we've ever seen right now," says Alastair Hatchett, the head of pay services for Income Data Services. "Most teachers have had quite significant increases in recent years, as have a lot of health professionals. "

It is true that salaries at the top end of the private sector - fat cats - far exceed anything paid by the state. But that's not the case for most senior jobs, or for many workers in education, health, local government and the civil service.

PENSIONS

Trade unions are still in talks with ministers over proposed reforms to public sector pension schemes. But even if the Government achieves all its aims, the occupational pensions on offer to the public sector will still be among the best in the country. All state employees will continue to have the chance to join a final salary scheme, where their pension benefits are guaranteed whatever happens on the stock markets.

In the private sector, such schemes are routinely being closed to new staff and even some existing members. Employers are shifting the risk of higher life expectancy and fluctuating investment returns on to staff, introducing money purchase schemes without guarantees.

Contributions are also falling. Although the most generous private sector employers may contribute as much as 10 or 15 per cent of salary into their employees' pensions, most pay a few per cent, or nothing.

However, while public sector pensions are still excellent, there have been cut-backs. New civil servants must wait until 65, rather than 60, to draw their pension. Local government workers are still fighting proposals to axe the rule of 85 - which allows them to retire at 60 if they have at least 25 years' service.

JOB SECURITY

Stephan Bevan, the director of research at the Work Foundation, points out that redundancies rarely existed in the public sector until recently. If jobs needed to go, employees were almost always moved elsewhere in the government machine. But in recent years, the position has changed.

"Because of the Gershon review [into public sector efficiency] two years ago, large parts of the public sector - especially the civil service - are now seeing job cuts," Bevan says. The Government has committed to axing 100,000 jobs by 2008 as a result of the Gershon review, in an attempt to achieve £22bn in savings.

"I think job security is still better than in the private sector, although there are still issues that haven't yet been resolved," says Dr John Philpott, the chief economist at the CIPD. "But people who might once have coasted in public service jobs, with less focus on productivity and efficiency, may now find they are in the firing line."

JOB SATISFACTION

In the 1990s, job satisfaction in the public sector plunged, partly due to low pay, but also as increasing bureaucracy crept into jobs such as teaching and nursing. According to a recent CIPD survey, this has now reversed, with today's public sector workers marginally happier on balance than those in the private sector.

However, Bevan suggests this trend may again be reversing. Pay has improved but, Bevan says, public sector dissatisfaction is rarely about money. " If you look at surveys that ask why people resign, it's generally not about money at all. It's about job satisfaction, feeling you're able to do your job, and escaping bureaucracy."

In any case, while teachers and nurses have had decent pay rises, these groups are still among the most dissatisfied when it comes to salary. Bevan says that for many, the feeling is that the pay rises have still not been enough to compensate for years of underfunding.

The manager who returned to the fold...

Jeff Porter is a 63-year-old former social services manager, who has devoted most of his working life to the public sector. Starting as a social worker, he moved into management before moving on to run an NHS hospital in the 1980s.

However, after becoming worn down by the political nature of his job, and also curious to experience working in the private sector, he eventually decided to make the switch in mid-career and took a job for a private business that managed nursing care homes.

"It wasn't actually that different to the public sector," Porter says. "It was still bureaucratic. Markets were important, but they weren't the be all and end all, as I thought they might be."

After three years in his new job, however, Jeff was unexpectedly made redundant. After working freelance for a while, he was eventually attracted back into the public sector by the job security and worked as a director of housing and social services in north London for several years.

While the pay and benefits are slightly lower on the public side, Porter says the security of working in the state sector has been a major attraction. Now approaching retirement, he remains loyal to the public sector and now works as a probation officer near his home in Suffolk.

The teacher who quit after seven years in the job...

Damian McGeary, 35, is an architectural assistant who quit his job as a maths teacher six years ago over fears that the stress was damaging his health. Having worked in education for seven years, the pressure of demands from governors, parents and staff had become intolerable.

"I felt stress from all directions," he says. "It's hard enough in the classroom. You have to work very hard to be a good teacher. But all the other pressures made it impossible. People think you have lots of free time, but that's a myth. All your time is filled with endless paperwork and meetings."

After quitting, Damian decided to retrain as an architect. He secured a job in an architectural practice and began a part-time degree at London Metropolitan University. "My earnings prospects are much higher in the private sector," he says. "And I feel much more in control. Things have been a lot less stressful."

... and the teacher who is sticking with it

Henrietta Wilson, 32, a fashion and textiles lecturer from south London, was enticed into the public sector three years ago. Taking advantage of the generous government funding and maintenance grants available for teacher training courses, she studied for a post-graduate certificate of education (PGCSE) at Greenwich University before securing her current job at the University College for the Creative Arts (UCCA) in Epsom.

However, although lecturers' potential salaries appeared generous at first, Henrietta soon discovered that UCCA, like many other educational institutions, was under pressure to manage its budget more tightly

As a result, she was offered a part-time job, working three days a week, but with enough work to fill a full 40-hour working week and beyond.

"I'm lucky that I'm in a position where I've got a partner who helps and supports me," Henrietta says. "My life would certainly be very different if I didn't have a partner who could help me out from time to time and maybe I'd have to move on."

Although Henrietta still enjoys her work, she says the workload can sometimes be extremely stressful. Even so, she's sticking with the public sector and is grateful for the financial support she received when starting out on her career.

... and the manager who feels betrayed

Paul Crawford, a 52-year-old surveyor from Brighton, fell out of love with the public sector after the Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea made him redundant last year and refused to pay the redundancy and pension package he had expected.

After working for a handful of London councils over a period of more than 20 years, Paul had worked his way up to become one of the more senior members of staff in his division. But after accepting a secondment outside of the council in 2003, he returned to find that his old job was no longer available. Keen to keep his skills within the organisation, the council moved Paul around a string of lesser jobs, with the promise that more appropriate employment was around the corner. But when he was eventually offered new permanent positions, they were lower paid and inappropriate.

When he turned the jobs down, K&C made Paul redundant, but refused to pay the enhanced redundancy package he had accepted, claiming that he had turned down two suitable jobs. "I liked working in the public sector, and was attracted by the security, good pension and good terms and conditions," Paul says.

He is now suing the council, and has a new job in the private sector, even though it pays less.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments