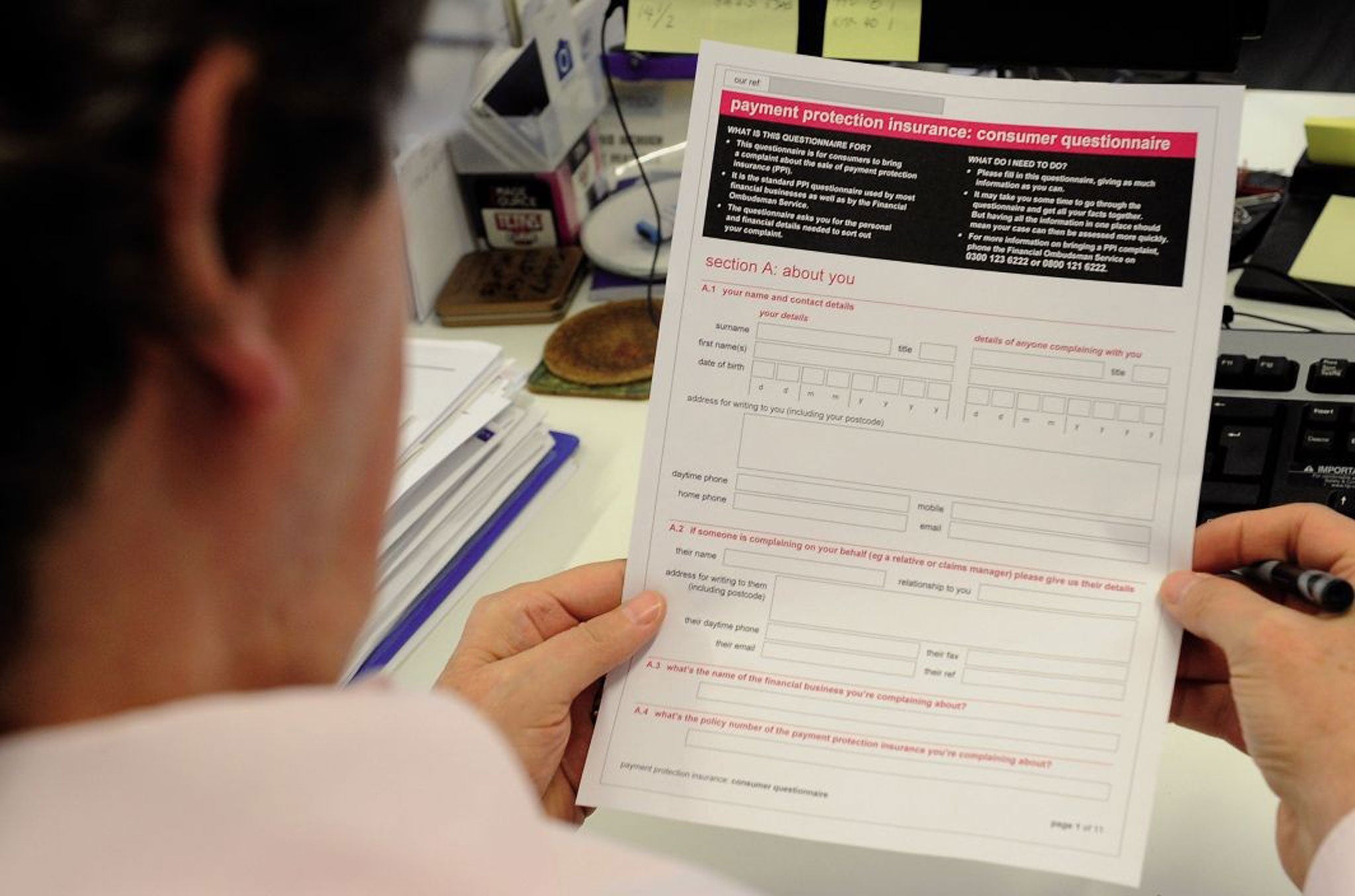

Hard-up families seek PPI payouts

Millions more may be due payouts for mis-selling, reports Neasa MacErlean.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Millions more people have potential payment protection insurance (PPI) claims which – unless they are time-limited – could stay at their present record levels for another three years. Banks had hoped that the numbers would go down but, instead, the Financial Ombudsman Service is adding another 1,000 complaints-handling staff and expects volumes to stay steady until 2016.

So far about three million consumers have sought redress over mis-sold policies, but this represents just one tenth of the PPI plans that have been sold. The Ombudsman, which handles cases from people who are still dissatisfied despite having been through the complaints process at the firm which sold them the policy, has just published its proposed budget for 2013-14, in which it says "this challenge seems likely to remain with us for sometime – probably for several years".

The biggest question-mark over the flow of complaints seems to be a proposal from the banks to set a time limit for the receipt of claims – possibly this summer – but if it happened, then banks might be forced to write to policyholders beforehand.

Many households may not even realise that they have a PPI policy (see case study), and others may not understand that the plan they was sold was not suitable.

Caroline Wayman, principal Ombudsman, advises people to ask themselves two questions to see if they were mis-sold. These are "Did they know they had PPI?" and "If so, did they want and need it?"

The Ombudsman is upholding consumer complaints in about 70 per cent of cases, awarding average sums of £2,750. The smallest awards – of about £200 – tend to go to people who had PPI on a credit card, but only for a short time and on small balances. The largest awards – exceeding £30,000 – are likely to go to homeowners who took a second charge mortgage on their home and who added PPI on top. One of the biggest amounts awarded came close to £100,000 for a frequent flyer who had several credit cards, all with PPI, and who used the cards extensively for large amounts.

People particularly likely to have cause to complain, according to Ms Wayman, fall into three groups: those with unusual employment circumstances (self-employed or on fixed contracts, for instance); people with health problems (who might not be able to claim on their policies); and those who were sold single-premium plans. A single-premium plan "can be a very expensive way of buying insurance", says Ms Wayman.

Compliance expert Adam Samuel agrees: "I am unable to identify a good sale to anyone with a personal loan of a single-premium variety."

He does, however, think that "a great many homes" were saved 20 years back by homeowners who had regular premium PPI plans attached to their mortgages.

Even if people get an offer of compensation from their bank, they may have difficulty knowing if the offer is a fair one. They can ask to see the calculation, and could also take the offer to the Ombudsman to check.

On top of a refund, the Ombudsman adds 8 per cent simple interest for each year since the PPI premiums were paid. But many banks have not been complying with the Ombudsman's rules, and they often seem to get the basic facts wrong about how long a PPI policy was in place.

Lloyds TSB was having 98 per cent of its cases decided in favour of the consumer when they went before the Ombudsman in the first half of 2012, according to the latest statistics. A spokesman says: "I can confirm that for a short period at the end of 2011 we experienced issues in distributing PPI compensation payments to customers. This issue was swiftly resolved, but it is likely to have had an impact on the rates published by the … [Ombudsman]. We are confident that more current data will highlight the significant investment we have made in our PPI complaints handling processes."

Barclays says that its 93 per cent consumer uphold rate before the Ombudsman "is a result of the fact that we were the first bank to offer gestures of goodwill payments to customers, which meant that we took back a large volume of claims from the [Ombudsman] … and proactively settled in favour of the customers in order to help the [Ombudsman]… clear a backlog."

However, Adam Samuel is not so sympathetic to the big banks and points to a fine levied this month on the Co-op Bank for, as the regulator, the Financial Services Authority (FSA) puts it: "Failure to handle PPI complaints fairly".

Mr Samuel says: "It is a mystery, though, why the FSA has not taken the same steps against the big four in exactly the same area."

A spokesman for the FSA says: "A very low uphold rate is one possible indication of complaints not being handled fairly. If there is a very low uphold rate [in favour of the institution] we would consider having a look at a firm."

In 2013-14 the Ombudsman expects to resolve about 245,000 cases – up 50 per cent on what it predicted for the current financial year. Citizens Advice is seeing complaints rates up about 21 per cent compared to a year before, and the chief executive, Gillian Guy, says: "The figure just keeps rising."

While claims management companies are being attacked by the banks for encouraging people to complain and then taking a quarter of the compensation, many households would not have realised that they had a case if they had not received a letter from one of these companies.

Anyone who gets such a letter can go through the complaints process themselves, or even with free help from a Citizens Advice Bureau – going first to the firm which sold them the loan and then if necessary applying to the Ombudsman. Gillian Guy says: "You don't need to pay anyone to do this."

Many people might not realise they were mis-sold as the policies were marketed in different ways. While the typical case of mis-selling is associated with someone taking out a bank loan or credit card, PPI was widely sold with particular purchases.

"In those situations, people's minds were on the double glazing or the car," says Ms Wayman.

Many cases are rather unusual. The Ombudsman recently upheld a complaint from a prison inmate who had to open a bank account to receive wages for work he was doing under prison guidance. He was sold PPI on the credit card he took out as well, but this would not have paid out as the plan excluded paying out to people, like him, who were on fixed-term contracts.

Some people's circumstances are dramatically changed by getting the compensation. They might be able to pay off a large debt or do up their home or help a child go to university.

People who do complain to the Ombudsman could find themselves waiting the best part of a year at the moment, now that so many are lodging claims. In cases of financial hardship, the Ombudsman can try to speed up the compensation process – something it will always try to do, for instance, if a family is in repossession proceedings.

"Tough times are really biting and people are in some real difficulties," says Ms Wayman.

Case study: Tesco borrower didn't know cover was added

William was surprised last year to get a letter from Tesco.

The letter referred to a loan he had taken out seven years ago and invited him to contact them if he had concerns about the PPI policy attached.

"I was aware of the PPI scandal but I didn't know it applied to us," he says. "I wasn't aware that I had been sold PPI."

But he had been.

He had applied online for the £8,000 loan and, without his realising it, PPI had been added. When he rang Tesco and told them that he did not know he had the cover they began a review of his file.

Soon after he got another letter saying PPI had also been added to another loan he had taken out with them. This was for £14,000 and took the total borrowed to about £22,000.

A couple of weeks later Tesco got back to him, offering to refund the full value of the PPI premiums he had paid, just over £3,000.

He and his wife, Nicky, discussed whether they should take the case to the Financial Ombudsman Service in case they would get more compensation that way.

But William felt Tesco had been straight with them, so they accepted the offer.

"Because we are getting our money back it is almost like an investment," he says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments