What it’s like to get out of prison at 72

‘For nearly two decades, Geneva Cooley had assumed she would die in prison’, writes Rick Rojas

In the pink-walled dormitory of the Julia Tutwiler Prison for Women in Wetumpka, Alabama, nearly all of the inmates had risen before dawn. Some sat on one another’s beds, applying makeup and sipping instant coffee. Geneva Cooley sat alone, having just put on her white uniform for the last time.

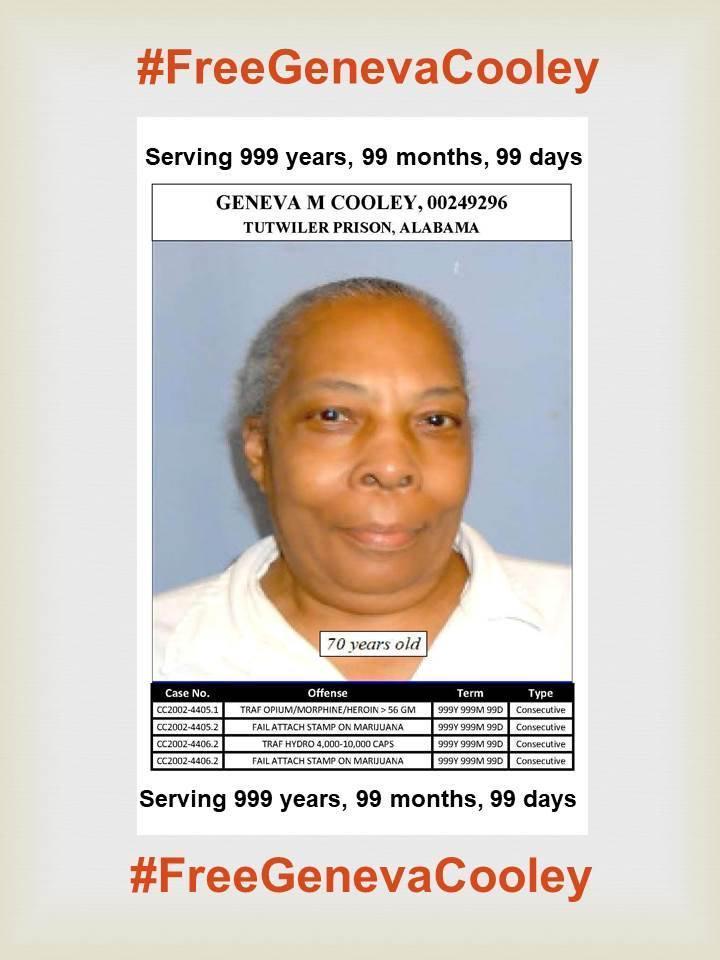

For nearly two decades, Cooley, 72, had assumed she would die in prison. She had been sentenced to life without parole on a slew of drug-related convictions, at a time when drug charges carried that stiff mandatory minimum.

She had accepted her fate. She got her own drug addiction in check, took some two dozen classes and eventually earned a place in the so-called “faith and honour” pink-walled dorm.

As she adjusted to the rhythms of life inside Tutwiler, a new normalcy took hold. She crocheted and watched the news. And the women around her – many of whom had been convicted of violent crimes, including the rape, torture and murder of a teenage girl – eventually became her friends, people with whom she watched The Young and the Restless.

Outside the prison’s walls, an evolution in the criminal justice system was taking shape. Activists had gained momentum across the country as they argued that life sentences without parole for nonviolent drug-related charges were unjust.

In Alabama – where the state’s prisons are overcrowded, understaffed and, according to a federal investigation this year, have “a high level of violence” – lawmakers last year reduced mandatory minimums to include the possibility of parole, motivated in part by the reality that lifetime care for inmates is costly.

In 2018, lawyers approached Cooley and said they wanted to take on her case. They argued that her sentence violated the Eighth Amendment, which protects people from unfair and cruel punishment. The district attorney did not oppose their claim for relief and a judge reduced her sentence to life with the possibility of parole, which she was granted.

But Cooley would not let herself believe she would be freed, not until she actually walked out of the prison’s doors. As she waited on that last morning in early October, she could not restrain how eager – but also how anxious – she felt about returning to a world and family, she had not seen in 17 years.

The world is not the same as when I came in here. I just want to live the rest of my life in peace with my family

“The world is not the same as when I came in here,” Cooley said, as she waited on her bare mattress, thin enough to be folded up. “I just want to live the rest of my life in peace with my family.”

Other inmates saw Cooley as tough and stoic, even ornery. (She said she was just a New Yorker.) But she also had a tender side, looking after newcomers who were often about the age of her grandchildren.

Many, particularly those sentenced to life without parole, found hope in Cooley’s victory. “In here, you have to have hope,” said Jennifer Jenkins, an inmate. “If you don’t have hope, you’re going to drown in self-pity.”

Annie Dennis, who at 82 was one of the few inmates older than Cooley, put her head on her shoulder, and Cooley’s stone facade cracked just a little, her eyes welling up. “It’s like saying goodbye to my sister,” said Dennis, who had been assigned to housekeeping with Cooley. For years, the pair cleaned the dorm and showers. Cooley stiffed back up, and she gave away the last of her things: books, shampoo, matches.

Finally, her lawyers came for her. The others cheered, patted her on the back and hugged her again as she left the dorm for the final time and walked into a bathroom, where she changed into street clothes for the first time in a while.

Her path to prison began in 2002 when Cooley, a native of Harlem and 55 at the time, took a train to Birmingham, Alabama, to be a drug courier, according to court documents. She was given heroin and hydromorphone pills by two people she had met in the parking lot of the train station. A few minutes later, in what she believed was a setup, she was confronted by police officers, who found her carrying a sock holding the drugs.

She was convicted four years later of trafficking in illegal drugs. She had been convicted before, and served time, in New York on forgery charges, having used fraudulent checks and stolen credit cards, she said, to support herself and her heroin addiction.

Cooley was among the last women in the Alabama prison system serving life sentences on nonviolent drug charges.

Everything she wanted to keep from prison could be stuffed into a brown paper bag and two manila envelopes. Cooley packed two books, one on crocheting and another on tai chi. She also held onto a stack of family pictures. She wanted nothing else.

Two of her lawyers, Terrika Shaw and Courtney K. Cross, walked with her outside. They were all smiles and laughter as they stood on the front steps of the prison entrance, and Cooley put on a pair of sunglasses they had bought for her.

Once outside Tutwiler’s doors, Cooley fast-forwarded through nearly two decades. She had a cellphone now and her lawyers showed her how to make and answer calls. (Texting would have to come later.) She had a video chat with her son after years of seeing him only in still photographs.

Later that day, Cooley moved to a transitional house in the state capital of Montgomery called Aid to Inmate Mothers (AIM), where she was among a half-dozen other women in various stages of adjusting to life out of prison.

She fiddled with Netflix on the shared house television and was introduced to YouTube. (Her first search: Smokey Robinson.) She was thrown by how much people relied on their phones, getting turn-by-turn directions from Google Maps or making a call with Siri. “Who is she,” Cooley asked. “How does she know my number?”

She went shopping for groceries. There were so many new flavours of crisps. But not everything had changed: “The Young and the Restless” still came on at 11.

Cooley wanted to rest. She had hardly slept her last night in prison, and her first day out had been exhausting. But first, she wanted to make a sandwich — with fresh bread, lettuce and tomatoes.

It was like we’re sending our mother off to college

Her lawyers had prepared her room for her. Her son had sent new pictures. “We bought you so much stuff,” said Shaw, one of her lawyers. “It was like we’re sending our mother off to college,” Cross added.

Spread across her twin bed were the things they thought she would need: clothes, a handbag, toiletries. Cooley noticed a box of black hair dye.

“Oh, y’all were really good!” she said, bursting into laughter. “I’m going to relax today and enjoy the atmosphere,” Cooley later told them, as they prepared to leave.

“Enjoy this,” Cross said. “We’re working to get you home home. We know you’re not home yet, but at least you’re free.” They had also bought her a night light because it was never dark in prison.

For the years of practice she had in biding time, it was failing her now. She watched Netflix. She made more sandwiches. She went to a salon, replacing streaks of grey with a caramel brown.

We’re working to get you home home. We know you’re not home yet, but at least you’re free

She had left one form of waiting around in prison for another one at the AIM house. The plan was to return to New York and move in with her brother in Queens once parole officials approved a transfer. She was ready to get there.

“I don’t want to be in Alabama,” she said later, sitting in her room, where messages like “Love makes everything grow,” and “Go confidently in the direction of your dreams,” were stencilled on the wall.

“I have nothing against the people,” she continued, “but I have nothing good to say about it.” She and her housemates went to a fair in Montgomery, but she tired of it fast.

And she waited for her son. The anticipation and anxiety were not unlike how she felt her last day in prison, waiting for her lawyers to come for her, each minute feeling as long as a year.

Her son had told her he was close, so she stood outside the house, watching every car that passed. Finally, he arrived. She rushed towards him, her grandson and granddaughter, who had driven through the night from Connecticut.

“Look at you!” she said as she wrapped herself around her son, Lamont, and her grandchildren.

After nearly two decades, she finally was back with her family. She was not home home. But with them, she felt like she really knew she was free.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments