Why women HIV patients are now engaging in clinical trials

Though the virus is the leading cause of death for women of reproductive age worldwide, says Apoorva Mandavilli, few have participated in drug research – until now

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Inspired by reports of a second patient apparently freed of infection with HIV, the virus that causes Aids, scientists are pursuing dozens of ways to cure the disease.

But now, researchers must reckon with a long-standing obstacle: the lack of women in clinical trials of potential HIV treatments, cures and vaccines.

Women make up just over half the 35 million people living with HIV worldwide, and the virus is the leading cause of death among women of reproductive age. In Africa, parts of South America and even in the southern United States, new infections in young women are helping to sustain the epidemic.

Women and men respond differently to HIV infection, but clinical trials continue to rely heavily on the participation of gay men. Trials of potential cures fare particularly poorly in this regard.

A 2016 analysis by the charity Amfar found that women represented a median of 11 per cent in cure trials. Trials of antiretroviral drugs fared little better; 19 per cent of the participants were women.

Vaccine studies were the closest to equitable participation, at 38 per cent.

“If we’re going to find a cure, it’s important that we find a cure that actually works for everybody,” says Rowena Johnston, Amfar’s director of research.

There are well-known differences in the immune systems of men and women. The flu jab produces a much stronger immune response in women, for example.

The response to HIV infection seems also to differ. The immune system in women initially responds forcefully, maintaining tight control over the virus for five to seven years.

But over the long term, this state of high alert takes a toll. Women progress faster to Aids than infected men, and are more likely to have heart attacks and strokes.

“There are all sorts of differences between men and women, probably mediated partially by hormonal effects,” says Dr Monica Gandhi, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

For example, the female hormone oestrogen seems to lull HIV into a dormant state. That may sound like a good thing, but the dormant virus is harder for the immune system, or drugs, to kill.

Some differences may be evident even before puberty: in one study, all but one of the 11 children who were “elite controllers” – people who seem to suppress HIV to undetectable levels without drugs – were girls.

Women also respond differently to some drug treatments.

Dolutegravir may increase the risk of neural tube defects in children born to women taking the drug, researchers have found. Nevirapine is far more likely to cause a severe rash in women than in men – yet men accounted for 85 per cent of the trial subjects in which the drug was tested.

These sex differences are likely to be germane to trials of potential cures, most of which are exploring ways to energise the immune system to kill HIV.

The number of men – and gay men in particular – in HIV trials has always surpassed the number of women. Early on, the epidemic was largely concentrated in gay men, who enrolled to gain access to new drugs as early as possible.

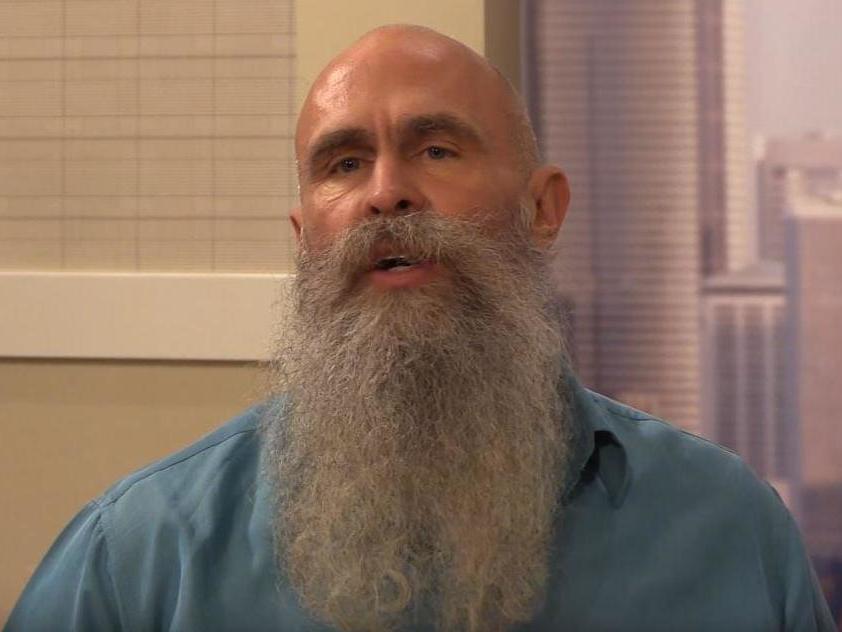

Gay men “were literally dying to get into these trials”, says Jeff Taylor, 56, an HIV advocate in Palm Springs, California, who enrolled in dozens of trials after his diagnosis in 1982.

Now, 30 years later: “It’s the same group of people, who understand the value of clinical trials,” he says.

Gay men have formed strong support networks that alert potential participants to clinical trials, and they often live in cities where the research is conducted.

By contrast, women with HIV tend to be isolated, and may not advocate for themselves. They may need help with child care or transportation, or be more comfortable with female doctors – accommodations few trials offer.

For women of colour, there is an additional hurdle: mistrust resulting from a long history of exploitation by medical researchers. “It’s a lot of stigma still in our community around research,” says Ublanca Adams, 60, who is living with HIV in Concord, California.

Scientists do not seem to know how to gain that trust, she says: “How information is given out to our community and our people is just not in a way to be inclusive, nor is it inviting.”

Adams says she has enrolled in a few observational studies, but does not trust scientists enough to participate in tests of a treatment or cure.

In the rare cases where scientists go the extra mile to enrol women, they face additional scrutiny from the Food and Drug Administration. (The agency has strict rules for including women of childbearing age.)

Most researchers simply opt for the easy way out and enrol men, collecting data from women only after a drug is on the market.

Two recent trials of long-acting antiretroviral drugs – which can be injected monthly instead of taken by mouth daily – have managed to attract significant numbers of women: 33 per cent of participants in one study, and 23 per cent in the other. But because of the promise of less frequent treatment, these trials were hugely popular and so had an easier time recruiting women than most.

“Patients lined up outside the clinic,” says Dr Kimberly Smith, head of research and development at ViiV Healthcare, the company that led the research.

In general, though, Smith says, trials in the United States struggle to enrol women, because about 75 per cent of the infected still are men.

Anticipating the need to test cures in young women, Bruce Walker and his colleagues at the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard have set up a group called Fresh in South Africa. Nearly 2,000 young women in the Umlazi Township check in twice weekly to be tested for HIV.

The researchers provide preventive therapy, but a small proportion of the women still become infected. Walker’s team is tracking their infections from the start and planning to test cures in the group.

Generally, however, it is difficult to get scientists to take the need to enrol women seriously, says Dr Eileen Scully, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

“Some of the hard scientists dismiss this type of discussion as being more socially determined, or some sort of women’s liberation thing,” she says.

Scully led the only cure trial so far to focus solely on women, testing whether a drug that blocks oestrogen makes it easier to kill HIV. From the start, the investigators had to make some concessions.

To skirt the restrictions limiting participation by women of childbearing age, Scully and her colleagues recruited menopausal women. But these participants have lower levels of circulating oestrogen, which may skew the results.

Still, the team has already made one key discovery.

“We were one of the fastest trials ever to enrol,” Scully says. “Women are ready to be engaged.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments