There’s one good thing about face masks, not being told to smile

Face masks are here to stay, for the time being at least. But it’s not all bad, one silver lining is that I don’t have to smile, writes Jessica Bennett

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For most of my life, I have had a minor but chronic condition – my face, when it is at ease, looks not just serious but mean.

There are women who will recognise this problem, particularly those who – around this time of the year, as the sun comes out and more of us are outside – have grown accustomed to being asked, “Why don’t you smile?” by anonymous people, usually men, on the street (that, or breathlessly practising how we can put more people “at ease” by softening our facial expressions in the mirror).

These smile critics are not only on the street, of course. Sometimes they are on television, offering advice to female politicians or female athletes, or politicians, suggesting that the speaker of the House might try smiling more, or President Donald Trump, who appeared to say it to his wife during a recent photo op.

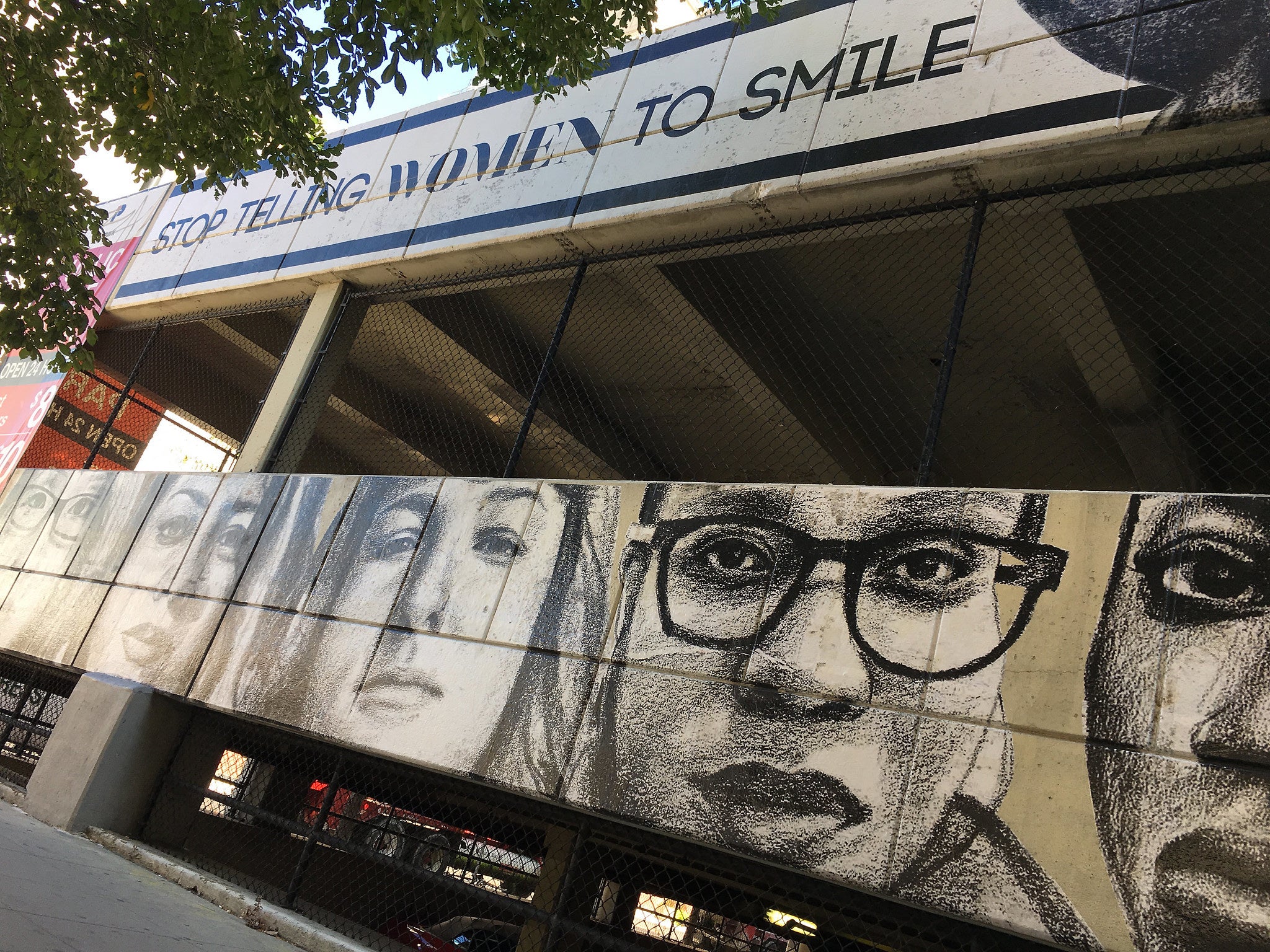

They have inspired at least one art exhibit, “Stop telling women to smile,” by Tatyana Fazlalizadeh.

But if there is one tiny, very tiny, silver lining to the reality that masks are a necessary component of our daily lives now, it is this: smiling on our own terms.

“For the first time ever, the weather getting nicer is *not* correlating with more men demanding that I smile, so that’s something. Thanks face mask!” Steph Herold, an activist and researcher in Queens, tweeted recently.

“Not having to fake smile or apologise for coming off a certain way has been such a weight off my shoulders,” says Talia Cuddeback, a recruiter in Austin, Texas.

“Wearing a mask is so liberating I might hang on to it, even if they do find a Covid-19 cure,” says Clare Mackintosh, an author who lives in Wales. “I walked past a building site the other day, and despite my resting bitch face, no one yelled at me to ‘smile, love’. No random men in the supermarket have suggested I ‘cheer up, it might never happen’ and not a single person has suggested I’d look prettier with a grin on my face.”

In the midst of a pandemic that has brought to light so many of the festering inequities brewing just underneath the surface – and as racial injustice takes rightful centre stage in American activism – feminine facial freedom is a minor victory. But it is also not nothing.

Studies have found that people are less likely to find friendly looking faces guilty of crimes, while people who look “happy” are generally deemed more trustworthy. There is all sorts of research about the subtle – and sometimes not subtle at all – race and gender biases wrapped into how we view another’s facial expressions (or, in some cases, our inability to see them), with people of colour often paying the highest price. In the pandemic, black men have expressed worry that facial masks will invite racial profiling by police.

When it comes to gender, there seems to be a deeply ingrained association between femininity and smiling. Studies have found that smiling babies are more likely to be labelled female by onlookers, while men view serious women as less attractive than those who look friendly (the opposite of how women view men).

Women do tend to smile more than men, across age groups and ethnicities. But it’s not necessarily because they are happier; in fact, women suffer higher rates of depression. Rather, says Marianne LaFrance, a psychologist at Yale University who studies gender and nonverbal communication, women feel pressure to smile, and they can be penalised if they don’t.

“Women get completely socialised that smiling should be the default expression on their face,” says LaFrance, the author of Why Smile? The Science Behind Facial Expressions. “So everyone expects it, including women themselves.”

Nancy Henley, a cognitive psychologist, has theorised that women’s frequent smiling arises from their lower social status in the world (she has called the smile a “badge of appeasement”). Others have pointed out that women are more likely to work in the customer service sector, where smiling is an asset.

But smiling has also been found in work settings to be associated with burnout, LaFrance says. (Goddess bless the camera-muting option on video conferences.)

Fifty years ago, writer Shulamith Firestone called for “a smile boycott”, in which, she wrote in The Dialectic of Sex, “all women would instantly abandon their ‘pleasing’ smiles – henceforth smiling only when something pleased them.”

In more recent years, Safeway workers have said that the company’s “smile and make eye contact” rule was often mistaken for flirting, while flight attendants for Cathay Airlines used the threat of not smiling as part of a negotiation tactic for higher pay. In 2016, after complaints from employees at T-Mobile, the US National Relations Board ruled that companies were no longer allowed to require employees to be cheerful.

When I’m at the store or the supermarket, I still try to reaffirm those working with a smile, but it ends up kind of me staring at them awkwardly

But perhaps the face mask obviates all of that.

In parts of Asia, masks have long been used for things other than simply blocking the passage of germs.

As Voice of America has reported, masks have been used to protect against heavy pollution and exhaust. Chinese youth have worn masks to build a “social firewall” against being approached by other people, while Japanese women mask their faces on days when they don’t have time to put on makeup.

Anna Piela, a visiting scholar in religious studies and gender at Northwestern University, has noted that Muslim women she has interviewed said they find it easier to wear masks because it has softened the stigma of face coverings.

“Suddenly, these women – who are often received in the west with open hostility for covering their faces – look a lot more like everyone else,” she wrote in an article in May.

Of course, there is purpose to the polite smile.

“The thing about facial expression is that it is so much a part of our lives – it keeps so much flowing, it keeps so much lubricated,” LaFrance says.

Indeed, suddenly I am at a loss for how to express my gratitude to my mail carrier – and give him an awkward thumbs up. I can’t smile at dogs, or children, or the protesters marching down my street (a raised fist felt more fitting anyway). I stare way too long at a woman jogging in a sports bra, trying to figure out through her mask if she is somebody I know – only to realise I look like I am leering.

“It creates this kind of weird anonymity,” says Kwolanne Felix, a junior at Columbia University, who recently wrote about how street harassers had missed the memo about Covid-19. “When I’m at the store or the supermarket, I still try to reaffirm those working with a smile, but it ends up kind of me staring at them awkwardly.”

Felix noted that as a black woman, she is often put in the position of putting white people around her at ease with a “warm smile”.

Dr Lynn Jeffers, the president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, notes that there is still a lot that can be conveyed through the eyes, voice and brows.

“I am definitely aware that I am way more expressive with my voice when I’m wearing a mask,” says Amy Zhang, a producer in Brooklyn who grew in Hong Kong during the SARS era, when masks were commonplace. “But it is a weird thing, at a time where we’re all going through such trauma and grief, to not be able to express a smile.”

As LaFrance describes it, it is the social, obligatory smile – “which is the one that women do the most” – that tends to be focused on the mouth muscles, easily covered up by a medical mask. But a genuine smile, or what is known in the field as the Duchenne smile (named for Guillaume Duchenne), a French anatomist who discovered it, involves both the mouth and the eyes.

“What’s interesting,” LaForce says, is that the facial muscle engaged by a genuine smile – what’s called the orbicularis oculi – can’t be used on command.

“So will the mask stifle a smile? No. Not unless it’s a fake one,” she says.

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments