A clean break: The wellness industry isn’t well, and people are finally waking up to it

After a decade of being bombarded by jade eggs, juice cleanses and charge crystals, consumers are beginning to reject the hyper-toxicities of wellness culture, writes Eloise Hendy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Gwyneth Paltrow touts the benefits of inserting a jade egg into the vagina and keeping it there overnight. Demi Moore and Miranda Kerr swear by the benefits of “leech therapy”. Kim Kardashian has her own blood injected back into her face. This she’s dubbed “really rough and painful”. Well, as those who stick to plain old moisturiser might say... duh.

It’s always been easy to mock A-listers for their ever-more-wacky wellness pursuits. Yet as extreme as they may be, their exploits are also low-hanging fruit in a culture that, for roughly a decade now, has been saturated with wellness down to its core. If anything, the outlandish activities of the rich and famous might actually serve as a nice distraction. Look around and you’ll notice that the concept of wellness has seeped into many aspects of ordinary women’s lives.

Dedicated followers of the industry might attend “wellness festivals”, “goddess gatherings” or “cannabis retreats”, or try out “vaginal steaming”. Whether self-proclaimed wellness devotees or not, women in London and Los Angeles alike go to SoulCycle, go on juice cleanses and eat nothing that isn’t “clean”. Others do yoga, charge crystals, download mindfulness apps, shun “toxins” for “superfoods”, and drink natural wine. Still more might say they “prioritise self-care”, or invest in supplements, or attempt “digital detoxes” and “intermittent fasting”.

When renowned American journalist Dan Rather presented a US news segment on the topic in 1979, he said: “Wellness – there’s a word you don’t hear every day.” How times change. Now, wellness is everywhere – an all-consuming concept that has transformed every brand and life experience it has touched, from food and travel to exercise and sex. It’s a powerful and hugely profitable global industry, valued at $4.4 trillion in 2020. That’s more than three times larger than the worldwide pharmaceutical industry. So, if wellness is now just an everyday word, surely we must ask: is everyone feeling good? Are we all well? Unfortunately, as with many individual wellness fads and trends, the evidence isn’t looking good.

American reporter Rina Raphael was, for a long time, a wellness industry acolyte. “While I was never into the more extreme wellness products or services, like yoni eggs or leech therapy, I did take a lot of the more mainstream ideas at face value,” she says. Indeed, part of the reason she accepted wellness concepts like “clean beauty, clean eating and energy-boosting supplements” was precisely because they were so mainstream. “They were everywhere,” Raphael stresses, “in every women’s outlet, all over Instagram, touted by celebrities, and even on grocery aisle shelves. My local supermarket sold detox kits!”

So, while she considered herself sceptical of “the more bizarre stuff”, like many thirtysomething professional women in the 2010s, Raphael still bought into a lot of it: “All these ideas that had very little, if any, scientific [basis].” One particular wellness drug of choice for her was The Class, which describes itself as “a cathartic workout experience that guides you to strengthen the body and notice the mind to restore balance”. A recent advert features Emma Stone in athleisure, peppily explaining that “the first time I ever went to The Class I just felt terror because I thought it was just too hard for me. And then I think I cried. And then I loved it. If I could do it every day I would.”

I was personally not feeling or performing any better. Rather I was consumed with ‘wellness’ and my body. It became work

A few years ago, Raphael’s account of The Class might have sounded similar. But then her father passed away. In the fog of new grief, she began to question the quasi-religious platitudes and gospel of community she was consuming in Sunday morning workout classes. She describes it as “the first crack in the armour of [her] otherwise complete devotion to [her] wellness regime”. Cracks kept appearing. “I became exhausted,” she says.

More than that, she realised she was becoming paranoid. Far from making her feel better, wellness seemed to be aggravating latent anxieties. She felt like punishing herself if she missed a single day of working out. She became terrified of parabens, or the preservatives found in many cosmetic products – “even though I later learned they’re one of the most tested preservatives”. Self-care became a job. “I was personally not feeling or performing any better,” she remembers. “Rather I was consumed with ‘wellness’ and my body. It became work.”

At the same time that wellness was feeling increasingly like work for Raphael, her actual work was becoming increasingly wellness-focused. Reporting on new wellness brands and trends for a business magazine, she kept running into problems. “I was hearing from scientists and researchers who informed me that a lot of these companies were completely pseudoscientific.” Her personal and professional lives collided. “I had to realise that the wellness industry isn’t well.”

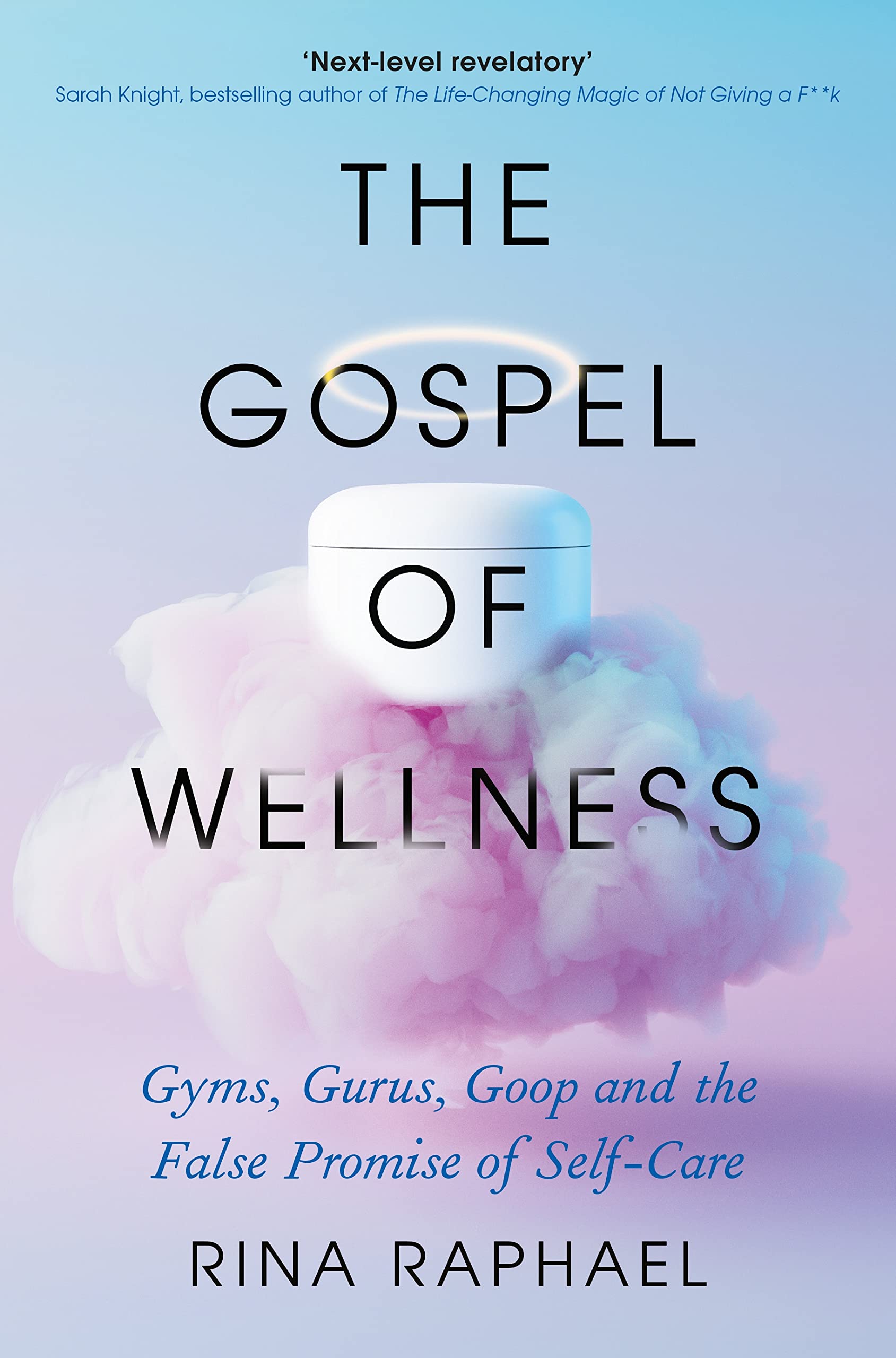

This growing scepticism led Raphael to write a book, The Gospel of Wellness: Gyms, Gurus, Goop, and the False Promise of Self-Care, which is out now. It’s an expansive survey of the contemporary wellness industry, and a debunking of sorts. Jumping from yoga to “clean” eating to “self-care”, Raphael digs deep into different facets of wellness, trying to sort the wheat from the scammy, overhyped and dangerous chaff.

One crucial chapter, titled “Gym as Church”, dives into the fitness wing of the wellness industry. Looking particularly at the SoulCycle phenomenon, Raphael suggests that the popular idea that fitness can and should provide “a transcendent collective experience” speaks to contemporary loneliness and isolation. Therefore we have “fitness families”, “deep connections with oneself”, wealthy white women with their boutique “tribes”. Yet, Raphael writes, “by boosting fitness stars to prophet proportions, SoulCycle inadvertently created untouchable gods”. Staff were regularly sacked with no explanation or compensation, and multiple clients and employees reported widescale sexist, racist and bullying behaviour. One anecdote in particular seems to sum up an essential cruelty lurking behind the company’s “all is wellness” smiles: an investigation by Vox discovered a note hanging in a SoulCycle office, written by a top instructor, that read “if someone asks you if you are back on cocaine or if you have an eating disorder, you know you’ve hit your goal weight”. SoulCycle reportedly did nothing, and only issued a statement when the cumulation of public criticism threatened to damage the brand. Or, in other words, once it threatened to hurt their bottom line.

Another chapter is titled “Is My Face Wash Trying to Kill Me?”. In it, Raphael takes aim at the beauty industry’s fast and loose approach to science. She grapples with the marketing mythology that “natural is best”, discusses the overblown claims from “clean beauty” brands, as well as cases of “clean” and “natural” products that have nurtured mould spores in their packets. “Wellness marketing perpetuates chemophobia,” she writes, “[or] an outsized fear of synthetic chemicals or ‘chemical exposure’.” Essentially, we’re easily duped by misinformation that looks a bit like science. As Raphael puts it: “We believe companies who say natural is better because it sounds right.”

The entire concept of wellness is founded on the idea that just because you aren’t sick, it doesn’t mean you’re not unwell. This means that the wellness industry relies on widespread sections of the global population regarding themselves as unhealthy, along with wealthy, well-heeled women diagnosing themselves as not up to scratch – then splashing the cash to try and fix it. This means, of course, that in the constant pursuit of ever-larger profits, the wellness industry will keep inventing new-fangled reasons for their marks to feel dissatisfied.

Instead of getting better, though, wellness devotees are getting paranoid. Even more concerningly, rather than becoming mini-Gwyneths, many seem to be turning into mini-fascists. Paranoia about parabens and toxins can evolve into anti-vax sentiment. From there, it’s easy to slip down a rabbit hole of conspiracy and alt-right thinking. Looking at the yoga and wellness gurus who’ve been hooked by QAnon, Kinfolk magazine recently described this phenomenon as “The Alt-Right Wellness Loop”.

There may be a light on the horizon, though. In a recent LA Times piece, Raphael suggested that “wellness products are losing their selling power”, and that the Goop-ification of consumerism is showing “increasing signs of decay”. Part of this may be an inevitable course correction – the trend pendulum swinging back. But there are also signs that a bigger wellness backlash is under way. While Gen Z in particular is reported as being more critical of wellness marketing and misinformation than any other generation, one study found that more than 67 per cent of adults report a growing mistrust of brands. A swelling tide of people are demanding more consumer trials and more clinical evidence. Essentially, people seem to be waking up to the wellness industry’s scams. More science. Less snake oil.

Writing in Studies in Popular Culture, feminist scholar Dr Carol-Ann Farkas neatly summarised wellness culture as “a radical turning inward of agency toward the goal of transformation of one’s own body, in contrast to a turning outward to mobilise for collective action”. In other words, if we’re kept busy fasting, exercising and buying, we won’t have the time, energy or will to challenge the workings of patriarchy and capitalism. Let alone can we begin to organise to dismantle those systems. Instead, wellness demands an individualistic retreat to self-care, self-soothing and self-optimisation.

In 2010, Farkas suggested that “raising our individual level of awareness, knowledge and expertise may take us from advocating the wellness of our own bodies to working together to improve the wellness of the body politic.” Thirteen years later, with countless cracks rupturing the wellness industry, it’s still one of the biggest challenges we have on our hands.

‘The Gospel of Wellness: Gyms, Gurus, Goop, and the False Promise of Self-Care’ is in shops now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments