When you are a new parent, there are a great many things you look forward to fondly: a first smile, perhaps; a trip with baby to the park on a sunny day; or a perfect morning moment as the little one wakes from their deep slumber in their cosy cot.

Expectations change by the time a second child comes along, and you know that the best you can hope for is the occasional, brief respite from their bawling, desultory swings in the drizzle and being greeted at 5am by a glint in baby’s eye and a steaming turd that baby’s nappy has failed to contain.

Sometimes, expectations become self-fulfilling, however. When our daughter was tiny, we had plenty of energy, and she seemed to have plenty of get-up-and-go. She liked always to be on the move, scampering about, and we responded in kind. As soon as we could, we signed her up for baby swimming: another activity to add to the list, we thought; and it’s never too early to learn an important life skill.

She took to it well, and we went regularly to public pools at weekends to keep the momentum going. Proper lessons started early, and at the age of five she had basically cracked it. By then, we knew she wouldn’t drown; and nearly a decade on, while she no longer swims regularly, she has the confidence of someone who feels completely at home in the water.

By the time our son arrived, a year after his sister was swimming laps in a Mallorcan pool, our own vim and vigour had diminished. As it happened though, he seemed a more placid creature, happy on his play mat, and content with trips to the cafe. He didn’t appear desperate to be endlessly active, and baby swimming felt like more hassle than it had once done.

Eventually, when he was four, we decided we’d better do the right thing and sign him up for some lessons, assuming that he’d have the natural coordination to make swift progress. Instead, it was like watching a brick trying to doggy paddle.

Studies a few years ago suggested that in a largish pool (800,000 litres or so), you can expect to find 75 litres of urine; probably more after the Year 3s have been in. But even knowing that, I would rather jump straight in and do 30 lengths of splashy breaststroke, than stay on the sidelines watching my floundering child.

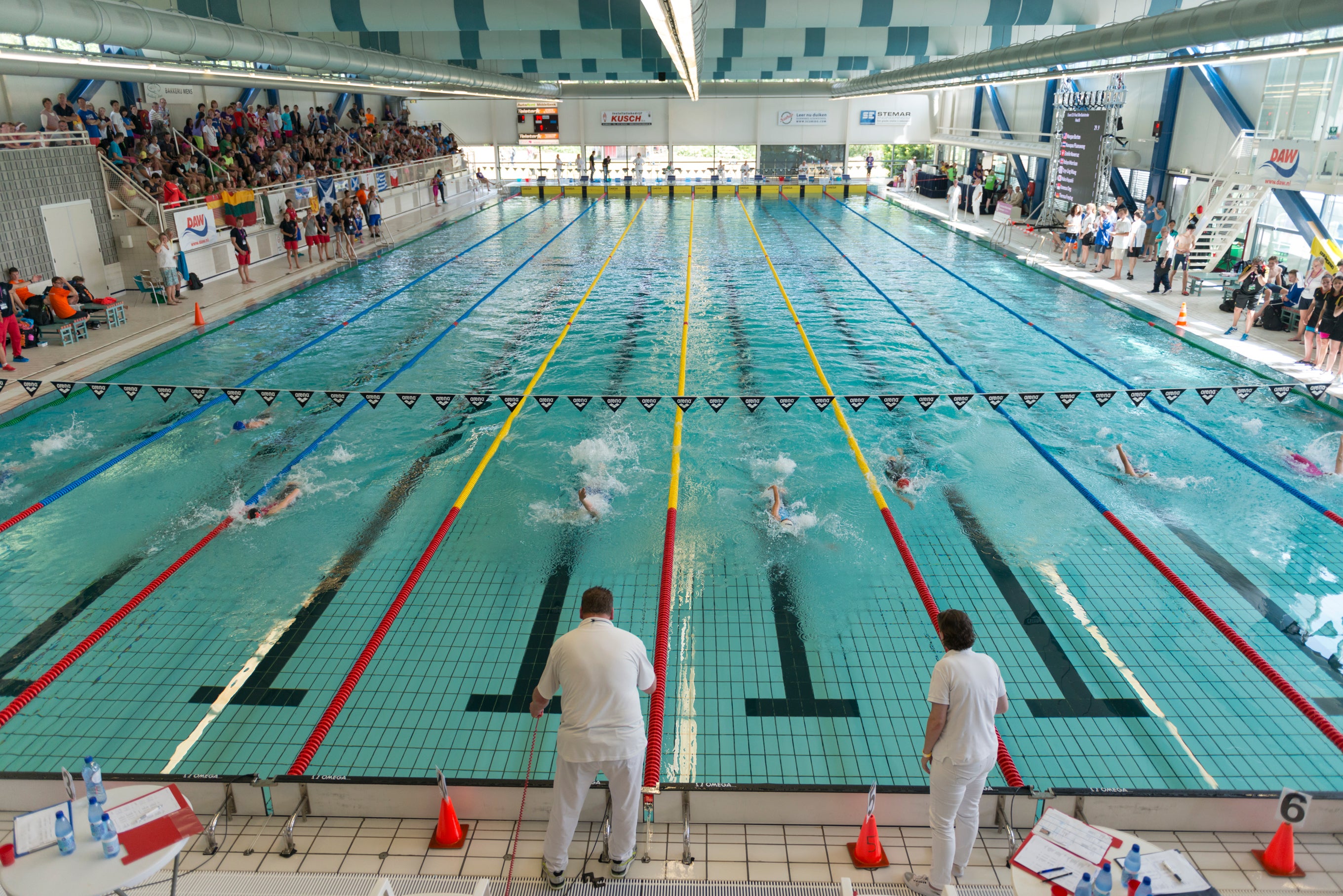

Over the last three or four years, he has made progress, but slowly. Covid interruptions are part of the story to be sure, and yet it is also plain that he simply does not have the instinctive aptitude – or indeed the motivation – that some other kids do. I went to his lesson the other day, for the first time in months, and was glad to see he has now made it to the deep end, even if his arms do come over at a peculiar angle and he occasionally has to pause for a few breaths. Once or twice, he got in a tangle with another child and I rose from my seat in the viewing gallery, ready to shout at the instructor if either of them didn’t emerge from the depths. But they always seemed to get back on their zigzag track.

Frustrating as it is, I do sympathise. I did not enjoy swimming as a child, and don’t much care for it now. Chugging up and down our local pool is dull; and I’ll only get in the sea if the sky is blue and the water is clear.

When I take my son for a non-lesson trip to the pool on a Sunday afternoon, neither of us actually wants to swim. I might do a couple of lengths, just to remind myself that I can; and I will probably encourage the boy to show me how his backstroke is coming on for a few minutes. But for the most part, we will stand 10 metres apart, waist deep, and throw a ball at each other, variously practising goalie saves, cricket catches or volleyball. Now, that’s the kind of activity swimming pools were made for.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments