The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How to tell if you’re a social media addict

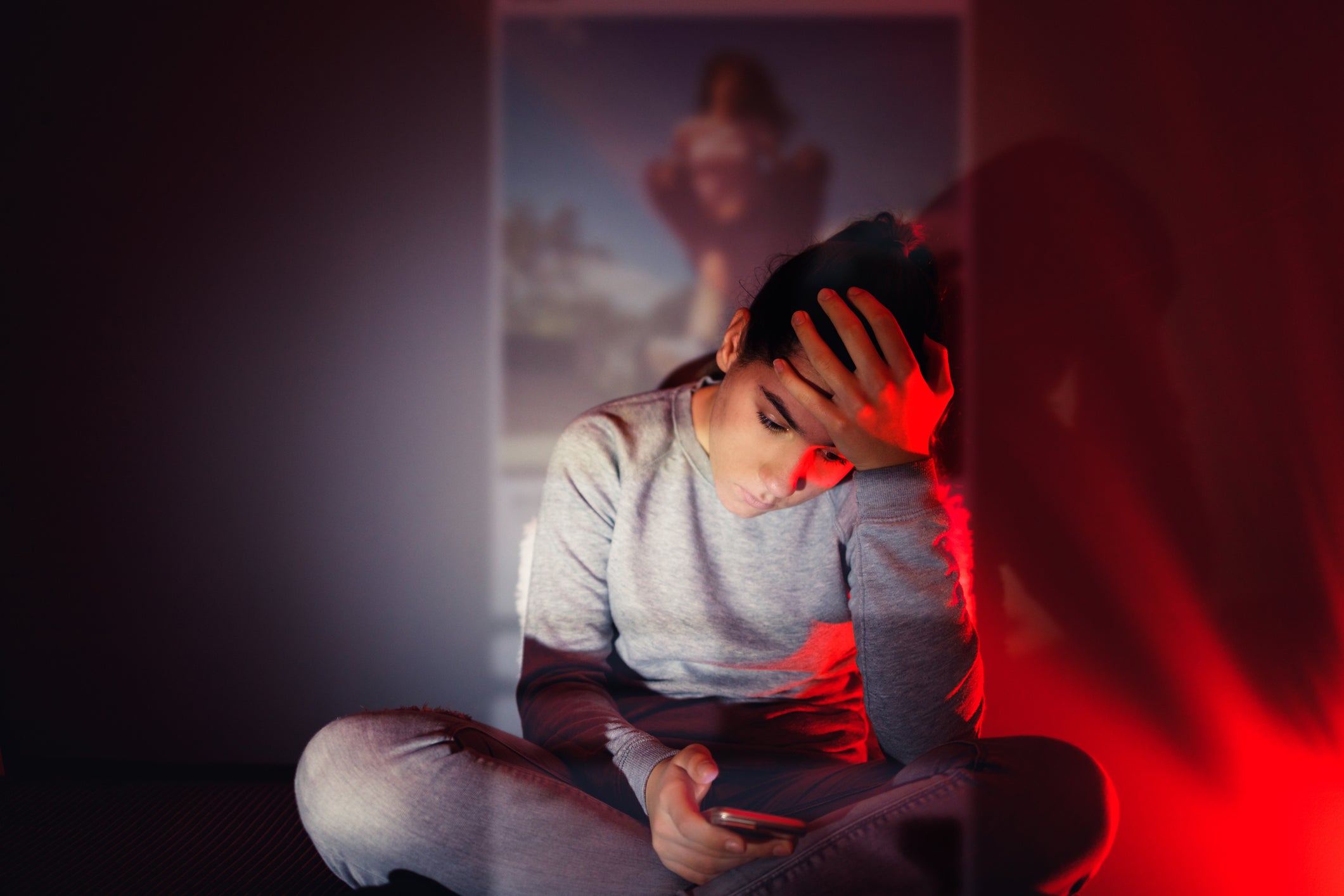

More than half of Gen Z believe they have a problem when it comes to scrolling, with an increasing number seeking professional help. Helen Coffey investigates what effects being constantly online can have on our mental health and asks the experts how to break the cycle

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A few weeks ago, I swapped my smartphone for a “dumb” phone to see what life would be like without constant connection. It was for a feature I had originally pitched as “my week using a Nokia 3210!”; alas, the chirpily optimistic brief changed once I realised how pathetically dependent I am on my device. Three days was the most I could manage – and one of the main reasons was social media.

The slide from being someone who “used Twitter a little bit” for work to fully fledged junkie has been slow and insidious – a years-long process that crept up so stealthily that I didn’t notice it happening. But in the aftermath of my dumbphone experiment, I was finally forced to face the uncomfortable truth.

I scroll on social media as soon as I wake up; as soon as I feel bored or frustrated at work; as soon as I have 30 seconds of downtime. I do it while watching a film on Netflix, mid-conversation with friends and, yes, even on the loo.

Sometimes I catch myself reaching for my phone for no discernible reason and put it back down. Less than a minute later my hand will, unbidden, pick it up again – like “Thing” from The Addams Family, scuttling around of its own accord.

But that’s just how it works, right? That’s how everyone feels about social media – it’s something you joke about with your friends, sure, but it’s not like a real addiction or anything. Not like I’m Aubrey Plaza’s character in the 2017 film Ingrid Goes West, spending my life obsessively checking Instagram and winding up moving to California to drink green juice and befriend slash stalk an unwitting influencer...

And yet, despite my cynicism, social media addiction “is absolutely as real an addiction as other addictions”, according to Lee Fernandes, lead therapist at the UK Addiction Treatment Centres (UKAT). “Addiction is defined as losing the power of choice, and so if social media has overtaken a person’s life, they have developed an addiction to it."

He categorises social media as a type of behavioural addiction – the umbrella term under which gambling, eating disorders, gaming, porn, shopping and sex addictions also fall.

“It actually has similarities to other types of addiction, namely behavioural disorders like gaming,” Fernandes explains. “The desire to game for as long as possible, and when not gaming feeling desperate to game again, is the same for someone who has a social media addiction; they are obsessed with being on social media.”

This could express itself in two main ways: either the person becomes addicted to creating content in order to get “likes”; or they use social media as a form of escapism from their real life, incessantly scrolling and living vicariously through the online world of others. “It is typically one or the other for social media addicts,” adds Fernandes.

Generation Z are possibly more in touch with their own weakness in this area than the rest of us. Three in five claim they’re addicted to social media, according to a survey of 2,000 young people conducted by education company EduBirdie. One in seven said they had even gone as far as seeking professional help to tackle their addiction.

It’s a problem that Sven Rollenhagen, a trained social worker who specialises in addiction, and the author of Scroll Zombies, is all too familiar with. “I have a lot of clients who are teenage girls and their behaviour, when I talk to parents about it, is the same as a person taking drugs or alcohol. They can’t put the smartphone away, it’s always in their hands, and when their parents try to stop them they get angry, scream and even fight.”

I have a lot of clients who are teenage girls and their behaviour is the same as a person taking drugs or alcohol

Rollenhagen previously worked with “traditional” addictions, such as substance abuse, before pivoting to working in the field of gaming addiction. Then, in the Noughties, he noticed a new addiction trend beginning to emerge with the introduction of the iPhone and launch of Facebook. “In one way, social media was an even harder addiction to crack than gaming,” he says. “The hardcore gamer needs a good computer and a console, and they have to stay at home to play. But with smartphones, you could have a small device with you at all times: at school, at work, on holiday.” There was never a built-in break.

While he initially questioned whether social media was a true addiction, Rollenhagen’s opinion “has changed quite a bit” in the intervening years; scientists have increasingly pointed out that social media use can prompt worrying patterns similar to other behavioural addictions. “I think there’s going to be a new official diagnosis in the next few years, like gaming disorder,” he predicts. The latter was officially recognised by the World Health Organisation in the 2018 edition of its international classification of diseases.

That’s because social media is quite literally designed to be addictive, both physically and psychologically. “We know that social validation lights up the same brain reward pathway as drugs and alcohol,” says Dr Anna Lembke, author of Dopamine Nation. “We also know empirically that people can get addicted to social media. We can then infer that social media addiction causes brain changes similar to those seen in addiction to drugs.” One study by Harvard University made this tangible connection, finding that self-disclosure on social networking sites lit up the same part of the brain that ignites when taking an addictive substance.

Likes and follows garner a hit of “feelgood” hormone dopamine, and dopamine “creates a positive association with whatever behaviours prompted its release, training you to repeat them,” The New York Times reporter Max Fisher observed in his book, The Chaos Machine. “When that dopamine reward system gets hijacked, it can compel you to repeat self-destructive behaviours. To place one more bet, binge on alcohol – or spend hours on apps even when they make you unhappy.”

I get chills when I read these words; many’s the time I’ve found myself scrolling before bed, and consciously thought: “Stop. Put the phone down now, please. Helen. Helen. JUST PUT THE BLOODY PHONE DOWN!” It feels an act of willpower that is simply beyond me, particularly when I’m tired.

Addiction to the algorithm is even harder for young people to fight – the frontal cortex, the bit of the brain responsible for self-control and willpower, isn’t fully developed until our mid-twenties. Meanwhile, one UCLA study found that the reward centres in teenagers’ brains lit up with activity in response to Instagram likes.

Although social media isn’t always obviously financially detrimental in the way that other behavioural addictions such as gambling and shopping are, it can lead addicts, driven by endless comparison and envy, to take financial risks in a bid to keep up with the online Joneses. It’s also associated with major mental health implications, including depression. “It can completely take over the person’s life – that is what addiction does,” highlights Fernandes. “When they’re not on social media, they’re thinking about what is being posted that they’re not seeing, what they’re missing out on, and they’ll compare the enjoyment of their lives to others’ and what they see online.” In one “worst case scenario”, Rollenhagen cites a client who spoke about contemplating suicide because he felt his life was “so bad” compared to the people he followed on Instagram.

The evidence shows that the more time people spend on social media, “the more likely they are to suffer psychiatric symptoms like depression, anxiety, inattention”, adds Dr Lembke.

It can completely take over the person’s life – that is what addiction does

Another potential impact is social phobia; ironically, given the name “social” media, these digital platforms can encourage us to become more insular, and less able to communicate and connect with people in the real world. Social skills are actually being eroded, not enhanced, by the apps, posits Rollenhagen. A study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine found that, of the 7,000 19 to 32-year-olds they surveyed, those who spent the most time on social media were twice as likely to report experiencing social isolation.

Sleeping habits are also frequently disturbed by overuse of social media, when we spend the time before bed relentlessly scrolling and refreshing rather than swapping out screens for more analogue pursuits, such as reading. Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh found a link between sleep disturbances and social media use. The blue light emitted by smartphone screens was concluded to play a major part – it can inhibit the body’s production of the “sleepy” hormone, melatonin – but how often participants logged on to, rather than the time they spent on, social media sites, was a higher predictor of disturbed sleep. It was the “obsessive checking” of an addict that correlated with the worst outcomes.

Not everyone will have a problem, though; the experts are quick to point out that social media can be a positive tool for those who have a healthy attitude towards it. So how can you tell if your penchant for scrolling has tipped over from harmless pastime to harmful addiction?

“We always advise people to think about their behaviour when they’re not on social media; are they happy to take a break from it?” asks Fernandes. “Or do they have thoughts and impulses to get back online as soon as possible? Are they able to socialise in real life instead of simply online? Are they able to continue with their ‘normal’ everyday life, ie going to work, seeing family/friends, or do they now spend their time on social media instead? Do they experience any physical withdrawal to being online – like nausea, headaches, sweating?”

If you can’t ever put your smartphone away and it’s always in your hand – when you go to the toilet, go to dinner, go to bed, when you’re travelling – that’s also a sign of addiction to watch out for, warns Rollenhagen, unwittingly hitting too close to home when it comes to my own toxic habits.

Seeking professional help might seem extreme to those of us who have normalised constant social media use, but it could be fundamental to discovering the “why” behind an addiction, advises the UKAT. “Sometimes, an addiction is simply a plaster covering an open, untreated wound,” says Fernandes. This wound could be low self-esteem, bad mental health, stress or anxiety, all of which can be treated “so that social media isn’t a necessity in that person’s life anymore”. Understanding our triggers can help us implement better boundaries for the future.

There are also straightforward measures we can put in place to limit our own use. A digital detox, where you significantly reduce the amount of time spent using electronic devices, “could be a wise precaution”, advises Addiction Center. “This can include simple steps, such as turning off sound notifications and only checking social media sites once an hour.” Rollenhagen agrees that creating boundaries where certain areas of life are smartphone-free – such as the bedroom and the toilet – is a good start, as is being strict about only doing one screen at a time (so no scrolling while watching a film).

He also recommends taking intentional breaks, starting with an hour and building up, using digital tools that physically limit the time you can spend on apps, and getting out in nature without your device. But the piece of advice that strikes me most is this: “Try to do something where you can’t have a phone in your hand: dance, dive, climb.”

I picture all of these activities in my mind – finally learning to Tango, watching the light slice nimbly through clear water, stretching my full length to reach the next brightly coloured handhold on the climbing wall – and then catch a glimpse of myself in reality, blank-faced, bent-necked, craned over the attention-sucking rectangle in my hand. “Stop. Put the phone down now, please. Helen. Helen. JUST PUT THE BLOODY PHONE DOWN!”

I think, finally, I’m ready to listen to the voice in my head.

If you have been affected by this article, you can contact the following organisations for support: actiononaddiction.org.uk, mind.org.uk, nhs.uk/livewell/mentalhealth, mentalhealth.org.uk.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments