Scrabble at 70: How an out-of-work architect devised the phenomenally popular word game

Alfred Mosher Butts, made redundant in the Great Depression, took inspiration from newspaper crosswords to create ultimate family argument-starter

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scrabble, the internationally popular board game, is 70 years old this week. In its three score and ten, Scrabble has brought friends and families together and, more often than not, driven them apart.

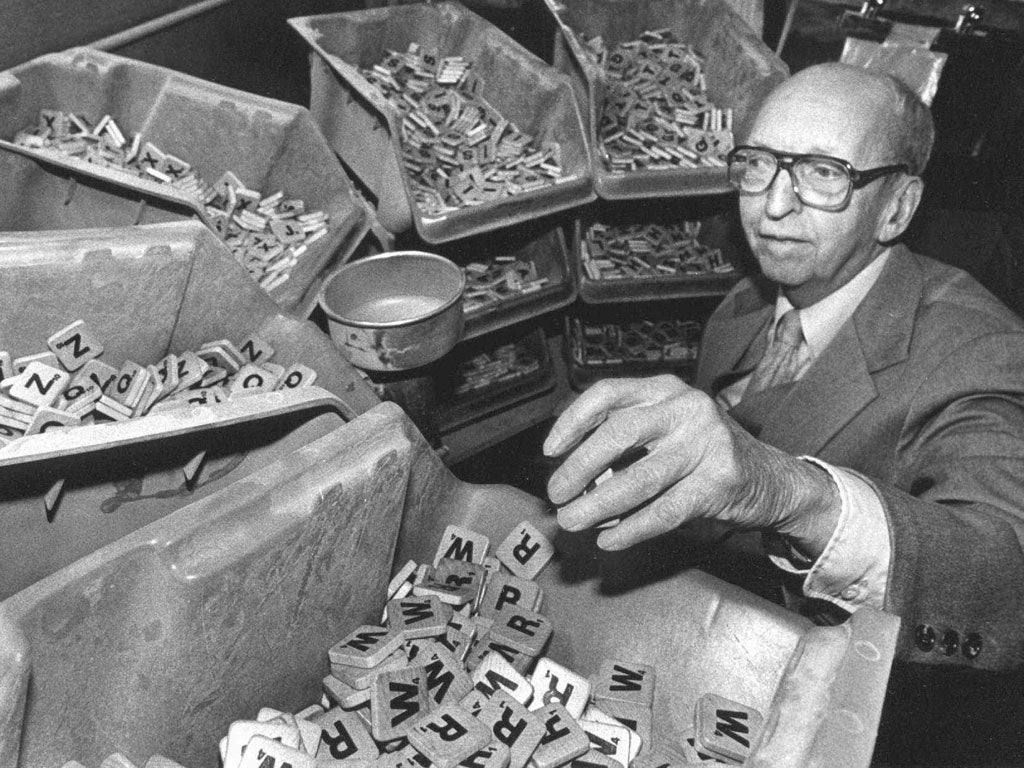

It was devised by American architect Alfred Mosher Butts of Poughkeepsie, New York, who worked on it during a period of unemployment after he was made redundant by his firm Holden, McLaughlin & Associates in 1931 when the Great Depression took hold.

Butts, then living in Jackson Heights, New York City, realised that all well-established family board games were either number games such as dice and bingo, strategy games like chess or word games and sought to combine the three.

Elaborating on an earlier version he had trialled known as “Lexiko”, Butts carried out a frequency analysis of letters by tabulating which words recurred most frequently in The New York Times, The New York Herald Tribune and The Saturday Evening Post, enabling him to determine the right value to assign to each letter of the alphabet according to rarity.

Butts found that just 12 letters - E, T, A, O, I, N, S, H, R, D, L and U – accounted for 80 per cent of those most frequently used. He also realised limiting the number of “S” tiles supplied would prove crucial, stopping players from repeatedly pluralising common nouns.

The 15x15 board itself took inspiration from a standard newspaper crossword and the working title was in fact “Criss-Cross Words”.

Despite the brilliance of Butts’s conception – the prototypes executed entirely in cardboard and without the aid of a computer – none of the major toy manufacturers took him up on his initial sales pitch.

In 1935, the housing market picked up and he returned to his old job with Holden, largely abandoning Criss-Cross Words beyond selling a handful of units between 1938 and 1942.

Then, in 1948, James Brunot of Newtown, Connecticut, picked up the baton. Brunot was a social worker seeking to make a modest investment to boost his retirement fund. Coming across one of the few versions of the game Butts had sold, Brunot contacted the creator, acquired the rights and gave him a royalty on every set subsequently sold.

After making some minor adjustments to the location of the premium squares on the board, moving the “start” point to the centre and thinking up the name by which it became internationally known, Brunot and his family began manufacturing copies out of a converted schoolhouse in Dodgington.

The Brunots produced 2,400 sets in 1949 – a rate of around 12 to 16 per day – but lost $450, with business only picking up in 1952 when Jack Straus, president of Macy’s department store, played it on holiday and enjoyed himself enough to place a large order on behalf of the retail giant.

Sales rocketed from 4,853 copies in 1951 to 3.79m in 1954.

The family soon found they could not keep up with demand and sold the game on to Selchow & Righter, who were among those to have rejected the opportunity presented by Alfred Butts before the war. They sold 4m sets in their first year and a global sensation was born.

Over the years, the rights have passed to Hasbro in the US and Mattel internationally. Scrabble has been played at international championships around the world, as video games and even on TV as a daytime game show on NBC.

Theoretically, the highest-scoring word in the game is “oxyphenbutazone”, denoting a type of anti-inflammatory drug used to treat arthritis and bursitis, which could garner the player 1,778 points if played just so.

It has never actually been used in a real game, however. The highest that has is “muzjiks”, a variation on the spelling of a Russian word for peasant, which earned Jesse Inman 126 points at the National Scrabble Championship in Orlando, Florida, in 2008.

Other potential high-scorers to keep up your sleeve for the right moment this Christmas include: “quizzify” (419 points), “oxazepam” (392), “quetzals” (374), “quixotry” (365), “gherkins” (180), “quartzy” (164) and ”syzygy” (93).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments