The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Four elements which every cook needs to master

Chef Samin Nosrat speaks about how she hopes to empower people to take the least convenient option and cook for themselves

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

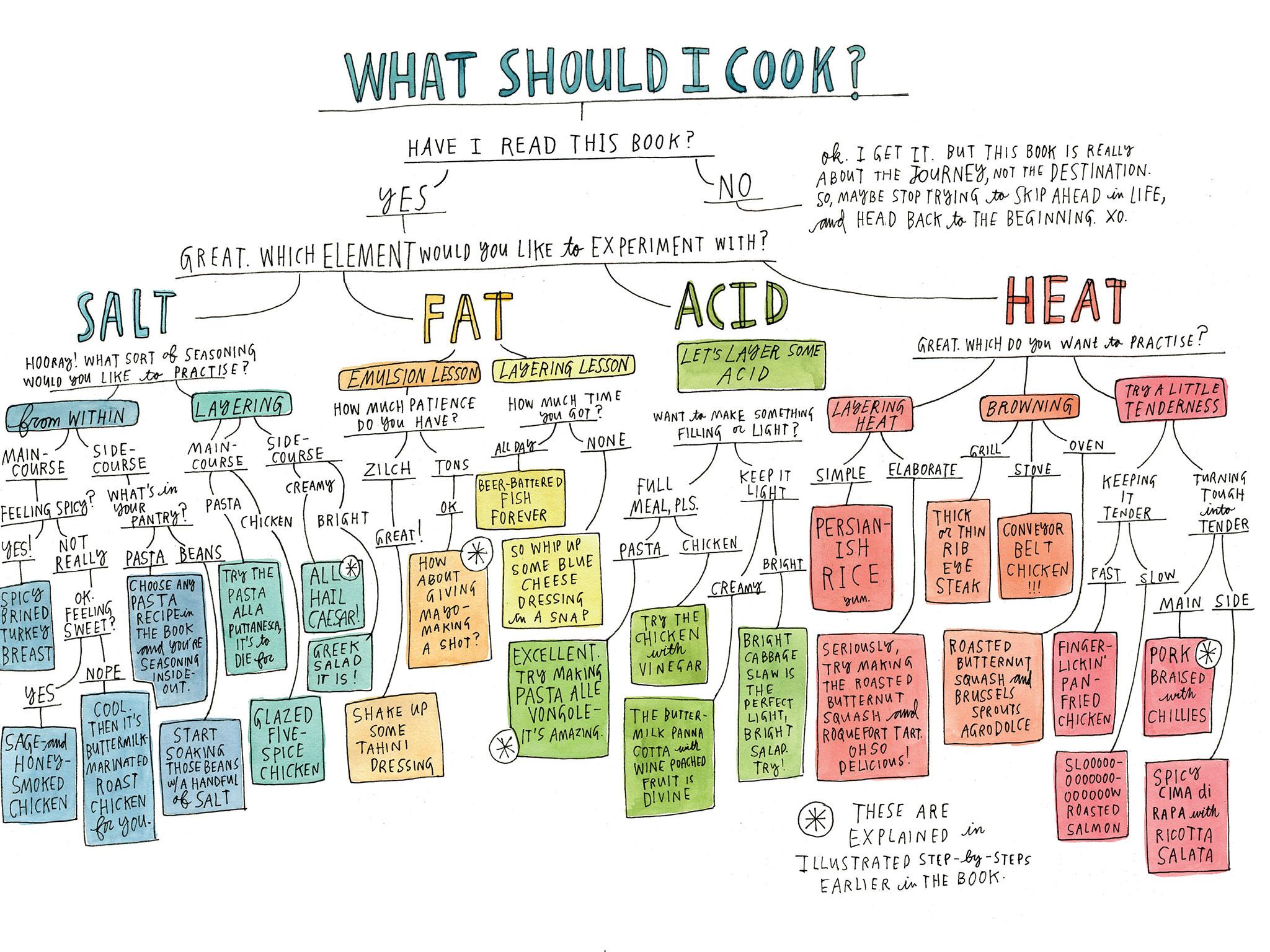

Your support makes all the difference.Salt, fat, acid, heat. That’s all that cooking delicious food boils down to, according to chef Samin Nosrat.

Getting to grips with these four factors will free us from relying on recipes and enable us to throw together delicious meals from leftovers in the fridge, she hopes. Mastering these elements of cooking will also demystify feeding ourselves and prompt us to reconsider ordering in food for the third time in a week.

In her new book of the same name, she shares the culmination of 17 years of cooking experience, which started out at the legendary Chez Panisse restaurant in Berkeley, California that changes its seasonal menu daily. It’s there that Nosrat first realised that cooking is all about those four components.

Salt, she writes, gives food a satisfying “zing” with each mouthful. It amplifies flavour, and affects texture. She adds not to worry too much about how much salt you add to food, as it’s almost certainly less than anything you’d buy prepared outside the home. And be generous when seasoning water for boiling vegetables, as it mostly ends up in the drain and will help to seal in the nutrients. Cooks should keep sea salt for everyday cooking, and Maldon for garnishing food.

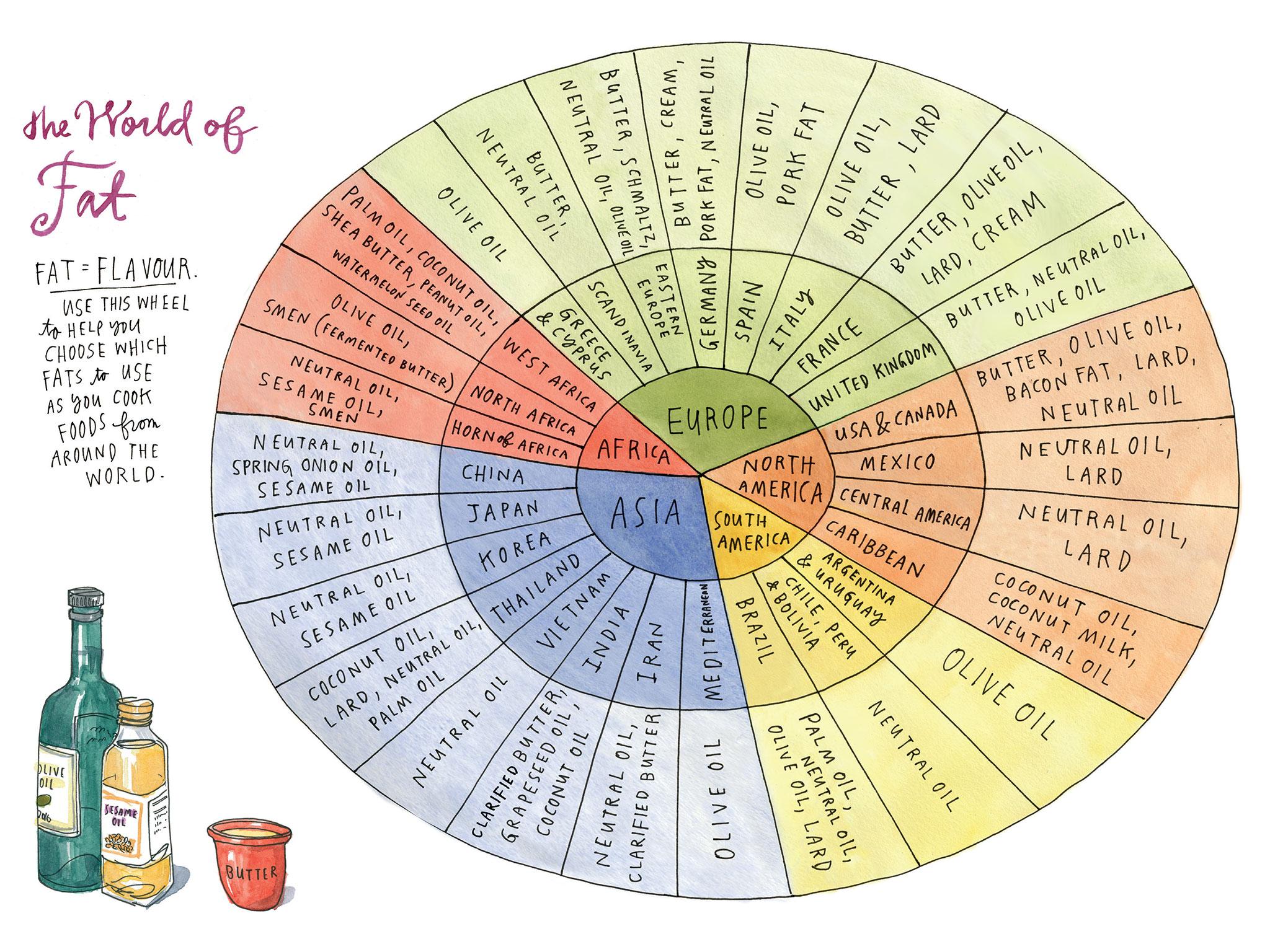

In regards to fat, she asks readers to imagine a vinaigrette without olive oil, sausage without pork fat, and baked potato without sour cream. Not only is it an essential energy source and required to absorb nutrients, but it adds flavour and texture – which she sums up as “crisp, creamy, flaky, tender, and light”. Among her tips is to prevent the degradation of flavour and release of toxic chemicals by preheating the pan before adding oil. And to stop heating butter before adding it to cookies to prevent them going flat.

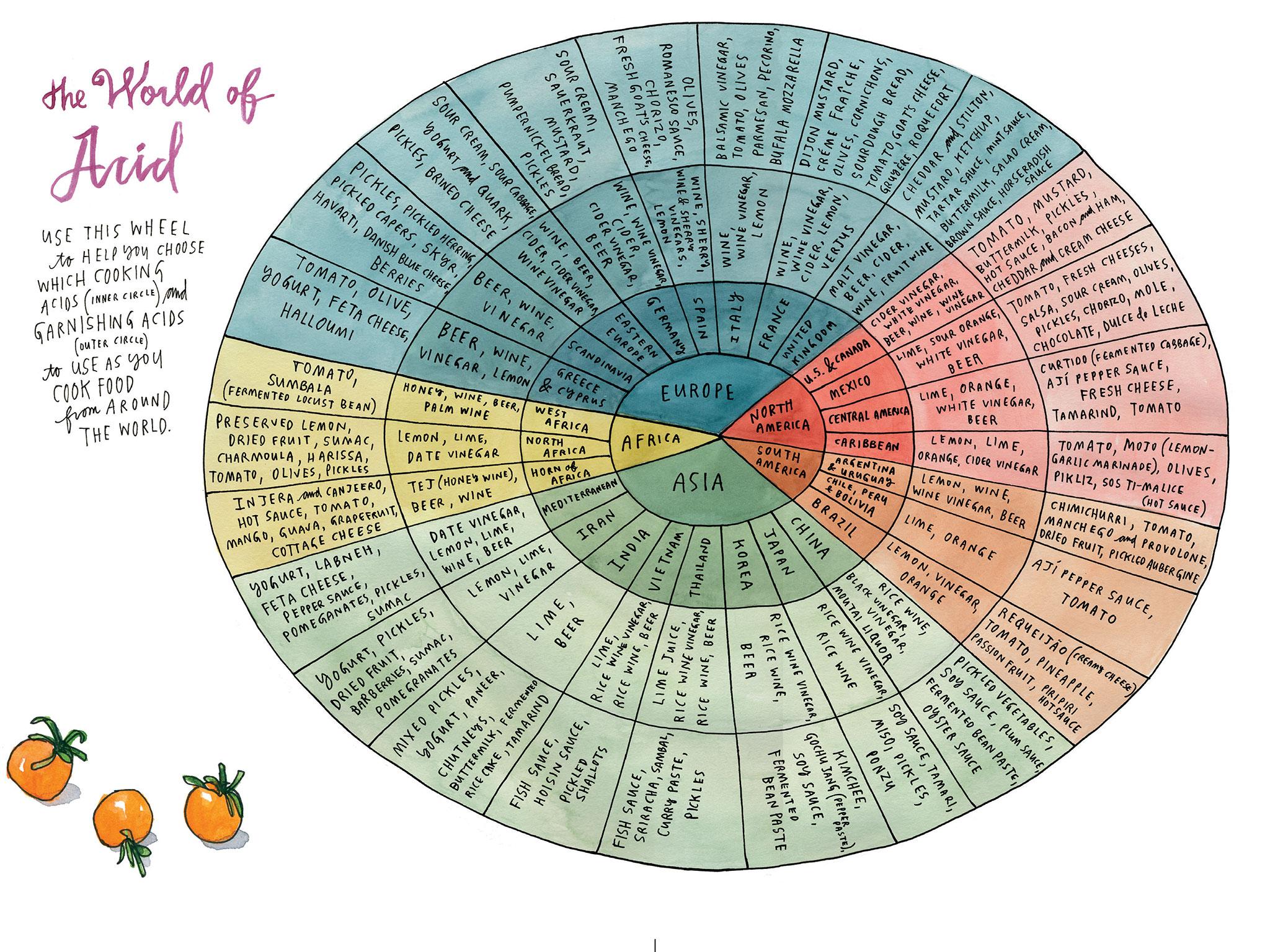

Acid, she points out, is the taste that makes food literally the most mouthwatering. It lifts flavour and sets off chemical reactions that change the colour and texture of food. She invites readers to consider which acid to use and when, whether cooking with them or garnishing.

Use salt to enhance, fat to carry and acid to balance flavour, she says.

Learning how to use heat, meanwhile, played a huge part in our evolution and freed us from having to spend most of our time chewing and digesting raw foods. To perfect heat, Nosrat says to work backwards.

“For example, if you want to end up with a bowl of flavourful, snowy white mashed potatoes, then think about the last step: mashing potatoes with butter and sour cream, and tasting and adjusting for salt,” she writes. “To get there, you’ll need to simmer the potatoes in salted water until they’re tender. To get there, you’ll need to peel and cut the potatoes. There’s your recipe.”

People tend to pigeonhole themselves as someone who can’t cook or can. How did we end up in a situation where some people see themselves as foodies and others completely delegate what they eat to others?

I think that speaks to society and our values as a culture and the way that modernisation has affected our relationship to food in the past 120 years more than anything specific in the kitchen. What that has lead to is a polarisation where people who are into cooking really immerse themselves and learn and watch and eat and taste and read and do all the things to support this, which some people might see as a hobby.

But modern life allows us to not be cooks. In a lot of ways this has fed into the idea of making cooking mysterious. There was a point in time when it was natural for a family member to teach others how to cook. It was one thing you learned to become an adult and that doesn’t exist anymore. Cooking has become this mystified thing that isn’t accessible, and on the other hand is fetishised, where we are watching cooking shows and competition shows and looking at food photos. But that distances a lot of people, which is a shame. I think anyone can be a good cook, it’s there under the surface for all of us and what I set out to do with the book is to write something that speaks to the broadest swathe of the population.

Social media has fed into the rise of “clean eating”. What are you thoughts on this movement?

I think it’s really unfortunate because it insinuates that everything isn’t clean and there are things that are somehow dirty. And that to me is really a poor choice of language and a clear example of how important language is. Of course people who really are leading the way aren’t out there with malicious intent.

I don’t want people to feel bad about what they eat, I just want you to know how to make it taste good and to feed people and take care of people. I appreciate how it puts an emphasis on vegetables. I think it’s a daily struggle for us all to eat enough. My friend Tamar Adler, the author of An Everlasting Meal, has a great line that people say “if you do this and that to a vegetable it’ll take out the nutrients”. But my stance is that any vegetable you eat is better for you than any vegetable you don’t. Doesn’t matter if it has olive or salt on it – just eat it and let’s start there.

Is clean eating making food more complex than it needs to be? People don’t even know if they should be eating carbohydrates or gluten at this point

I won’t go to the length of singling it out as the great perpetrator of this as it goes back a really long time. Since the 1950s there has been this idea that if you avoid things then all your problems will be solved. The list of those things has been rotated and replaced. It just happens that clean eating and paleo are the current version. I think to me that it speaks to a greater problem that as humans and Westerners we are disconnected from the most basic of human necessities, which is how to feed ourselves. That speaks to the power of the media and at least in the US, the government interfering in agriculture and giving certain crops subsidies and others not. So there are just huge lobbies that have affected the messages we get from the government on what is healthy to eat. When I was growing up, there was a campaign called “Pork: the other white meat” because it had been maligned and another campaign for eggs because it was decided they were unhealthy because of cholesterol. There is this idea of basic balance and moderation and human knowledge that was lost.

If you think about the original way humans evolved to eat and in countries that haven’t been devastated by globalisation there are seasons and periods of richness and poorness, so you don’t always have the most extravagant ingredients. In Southern Italy, historically families would slaughter three pigs. One would go to the land owner, one they would sell for income and live off the third one for an entire year. Of course pork wasn’t deeply unhealthy nor did it need to be encouraged. They had a really modest amount to keep them going for a whole year. And I think that when things are readily available and we eat a whole bag of chips without thinking that is when you get into dangerous territory. But that’s not to say they’re inherently bad.

Your book feels like going to cookery school. It’s so detailed. Do we need to educate people better so writers don’t need to teach us how to eat properly?

What else is there if there isn’t the most basic act of feeding yourself? It’s the act on which the rest of life is built. Of course it deserves our attention and basic commitment to learning. I’m trying to make it clear that it’s not that complicated or hard. And it’s so hard it’s because modern life has been engineered to make it hard for us to make good choices. Between meal kits, and food delivery, and ready meals and fast food and eating out it has to be a deliberate choice to cook for yourself and learn how to cook. And I guess my hope is to empower people to make that choice in the face of all of these forces that are making it the hardest and the least obvious choice.

In terms of the countries that the UK and US should learn from, where should we look to? You have Iranian heritage, can we learn from Persian food?

Iran isn’t immune, either. There’s an app called Mamanpaz where a local home cooked meal can be delivered to you. To me anywhere that has still managed to hold on to culinary traditions of their past would be a great place to turn to. I lived in Italy for two years. I lived in a few different regions when I was in the north, I cooked a dish from Tuscany and it’s a really common dish, it’s foundational and I cooked it in Piedmont and they were like “what is this strange thing you created?!”. Their cooking is so insular that their traditions are so well protected they have no interest in the foods of other countries but also other parts. That same stubborn commitment to their traditions is what keeps tradition alive. Iranian restaurant culture only consists of kebab restaurants because kebabs are not what are generally made at home. Really elegant and flavourful dishes of the Persian kitchen are made at home. That cooking and that idea that you invite people over and teach your children how to cook – that is what has kept that tradition alive.

What food can you not live without?

Parmesan cheese! It’s the most amazing taste. We have five tastes but fat is on its way. Sweet, salt, savoury, bitter, umami and now theoretically fat. And parmesan is a rare food that hits all of them. It triggers every taste bud and the fullness of the taste experience. To me even if I were just catching fish that would help!

What food would you never eat?

I’m pretty squeamish about entrails. I wish I were more adventurous and could proclaim my fondness for offal. I like liver but things have to be dire before I enter the world of tripe and haggis.

What do you want people to take away from the book?

I want to create a new vocabulary and think about salt, fat, acid and heat before they cook. I want it to become reflexive for everyone. The point of the book is to help people understand it. I want regular people to stand up in their kitchen and say what is the salt, fat and acid going to be? If that could be the takeaway I would die of happiness.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments