The verdict on last time a Prince was in witness box: disastrous!

The Prince of Wales ended up in court in 1890 in what became known as the royal baccarat scandal - it did not go well, writes Tara Cobham

A royal scandal in the Victorian era involving gambling, an illegal card game, and accusations of cheating set the scene for the last time a prince stepped into the witness box in a British court.

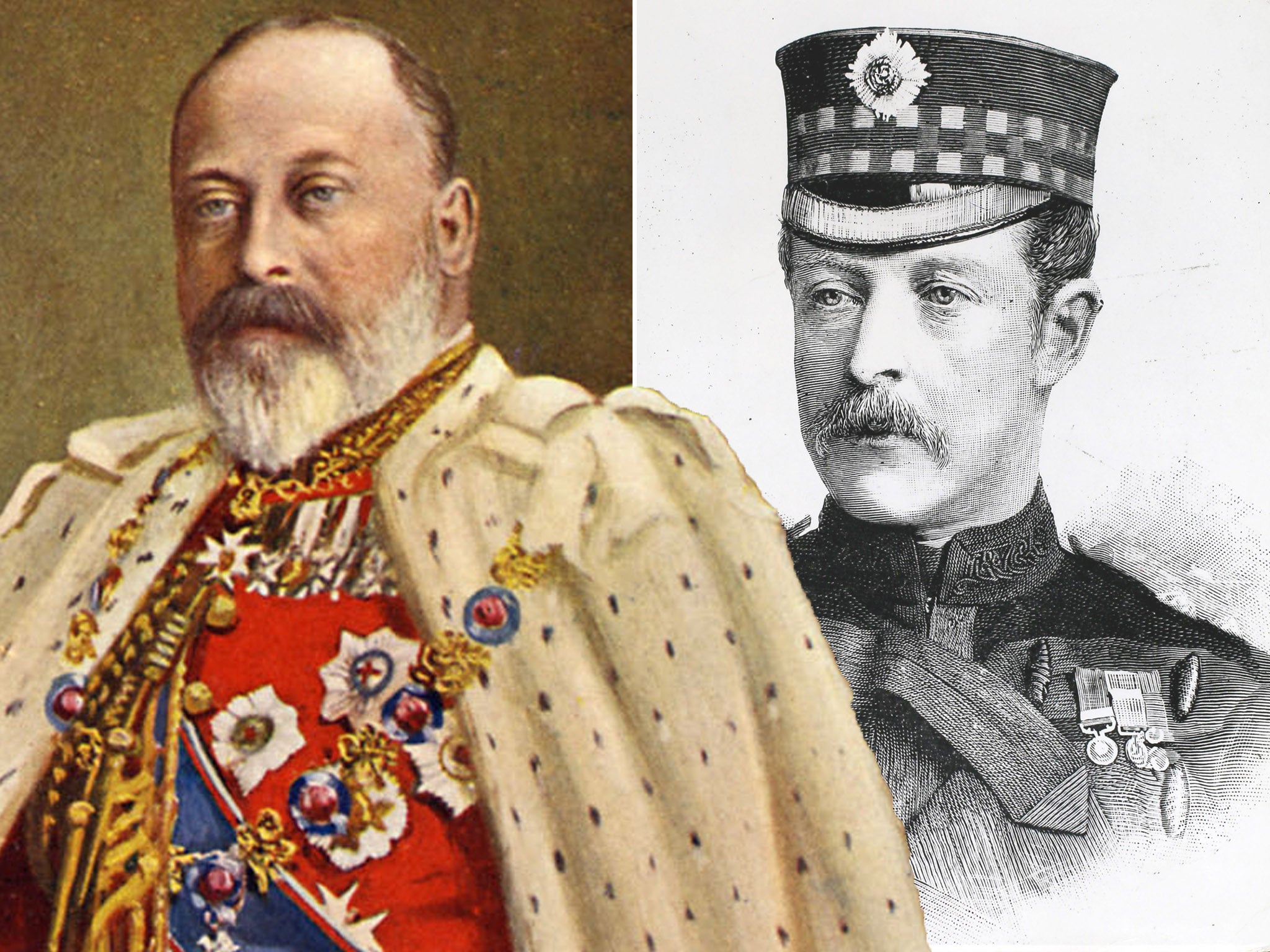

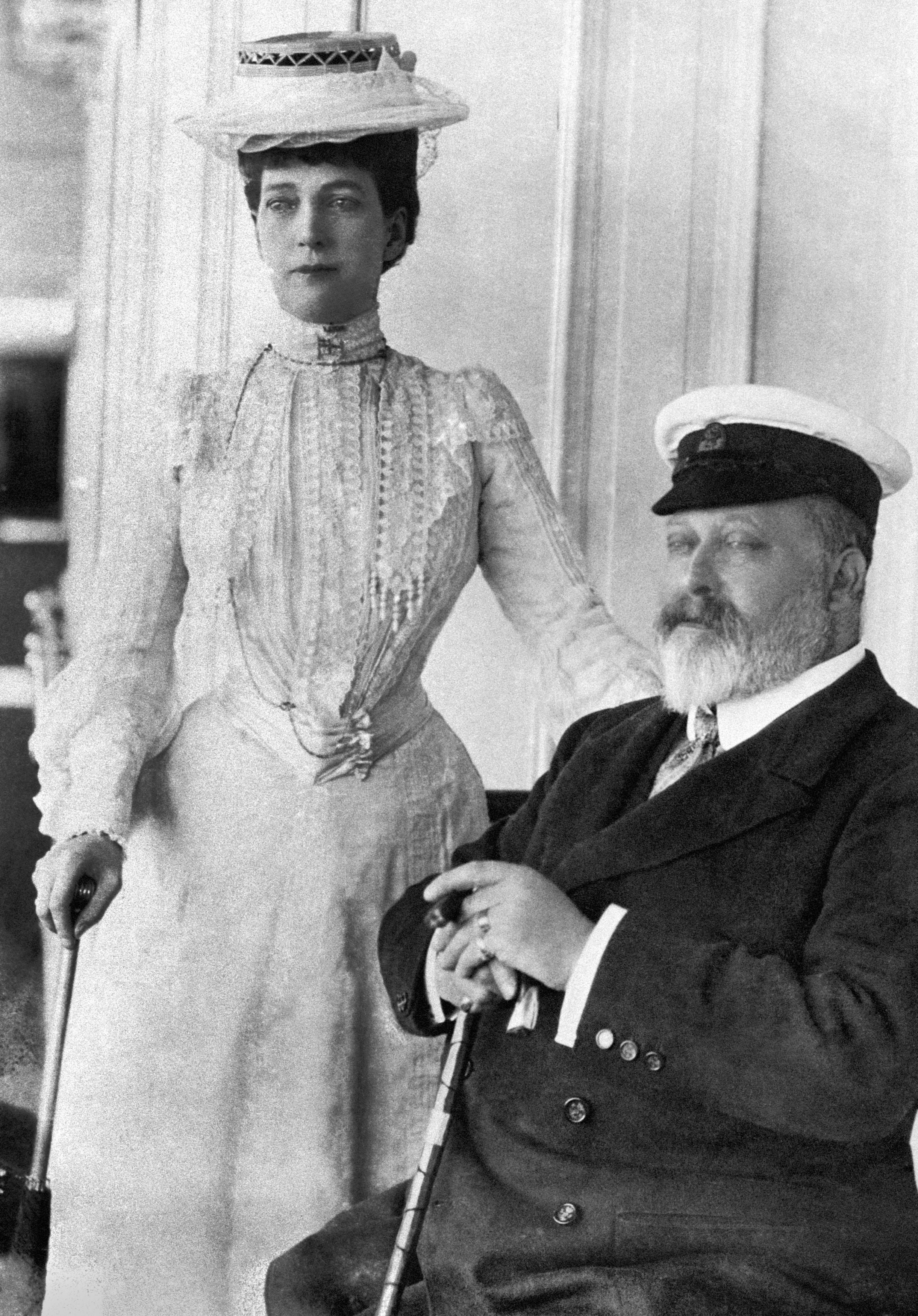

Royal fans have to look back 130 years to find accounts of an “extremely nervous” and pale-faced future King Edward VII giving evidence in a slander case after a spectacular falling out with his best friend in 1890.

Centred on the illicit card game of baccarat, the furore – dubbed “the royal baccarat scandal” or “the Tranby Croft affair” – proved an unedifying moment for all involved, and distinctly damaging for the crown.

After the Prince of Wales’s former close friend, Lieutenant Colonel Sir William Gordon-Cumming, 4th Baronet, of the Scots Guards, was accused of cheating in the game, Lt Col Gordon-Cumming took his accusers to court and the prince acted as a key witness for the defence.

The “poor showing” of the nervous Prince of Wales in particular proved “disastrous” for the royal family, according to royal commentator Richard Fitzwilliams.

As a result of his appearance, it was agreed that “royals don’t appear in court”, Mr Fitzwilliams said, citing the adage: “Never complain, never explain.”

Therefore, it is “very momentous”, said Mr Fitzwilliams, that Edward VII’s great-great-great-grandson Prince Harry is set to testify at the High Court in his lawsuit against the publisher of the Daily Mirror this week over alleged unlawful information-gathering.

But he warned: “If Harry doesn’t perform well, it will be a form of repetition of what happened with Edward.”

The Tranby Croft affair was so called because that was the name of the country house in east Yorkshire, belonging to Hull shipping magnate Arthur Wilson, where the future King Edward VII was staying for the Doncaster races along with friends including Gordon-Cumming.

Like many royals before and since, the prince, known as Bertie, dabbled in debauchery. He had a reputation for gambling and womanising, with Gordon-Cumming even lending his home to the prince for meetings with his mistresses – although the key was always to do so out of the public eye, in order to avoid a scandal.

Due to its heavy reliance on luck and the huge amounts of money involved, baccarat – a game not dissimilar to blackjack – was not only looked down on in certain polite circles, but was illegal in public, and illegal in private when playing for money – and Queen Victoria’s son was a huge fan.

So the group at Tranby Croft followed their two days at the races with two nights of playing baccarat – and this was when the trouble began.

Over the course of the two evenings’ play, Wilson’s son Stanley and his son-in-law Edward Lycett-Green began to suspect that Gordon-Cumming was cheating. While the prince did not witness any cheating himself, he believed the accusers.

The situation spiralled, and royal advisers panicked about the dispute becoming public.

Consequently, Gordon-Cumming was forced to sign a statement agreeing to keep the accusations private and never play cards again. The only other option was to be exposed as a cheat – so he signed.

However, attempts at keeping that evening in 1890 a secret failed, as gossip spread like wildfire, and Gordon-Cumming felt he had no choice but to take his accusers, the Wilson family, to court – which meant that the future Edward VII found himself stepping into the witness box to testify against his former friend.

One contemporary report described what it was like to see the prince give evidence, according to The Guardian: “Though it only lasted 20 minutes, the examination of the prince evidently wearied him exceedingly, and made him extremely nervous. He kept changing his position and did not seem able to keep his hands still.

“When a question more pressing, more to the point than usual, was put to him, the prince’s face was observed to flush considerably, and then pale again, showing the state of nervousness in which he found himself.”

Gordon-Cumming not only lost his case but retired from society. However, the case remained controversial, with members of the public claiming the judge was biased towards the prince.

The sight of a royal appearing in court left a stain on the reputation of the royal family, which courtiers had every desire to avoid repeating, especially after the prince had already appeared in court as part of a notorious divorce case 20 years prior.

The prince appeared as a witness in a divorce case in 1870 when Lady Harriet Mordaunt falsely accused the heir to the throne of being one of her lovers.

She confessed to a string of affairs, telling her husband Sir Charles Mordaunt of her exploits after fearing she had caught syphilis and passed it on to their newborn daughter. Sir Charles filed for divorce.

Letters from the prince – who had many mistresses, including stage actress Lillie Langtry and Queen Camilla’s ancestor Alice Keppel – were found in Lady Mordaunt’s desk.

The prince was briefly cross-examined in court during the divorce proceedings over whether there had been any “improper familiarity or criminal act” between him and Lady Mordaunt, but replied, in a very firm tone, “There has not,” which prompted a burst of applause within the courtroom.

Lady Mordaunt was declared insane by the jury, the divorce case was dismissed, and she spent the rest of her life in an asylum.

In more than 130 years since the baccarat scandal, no prince has stepped into the witness box – until now.

Describing the case as “gladiatorial theatre” and a “feeding frenzy”, Mr Fitzwilliams compared the intense media interest in Harry’s case to Edward’s and said: “Having a member of the royal family in the witness box is sensational – anything could come up.”

Mr Fitzwilliams predicted the Duke’s appearance in the witness box could bring some “very uncomfortable” moments, and potentially embarrassing scenes for the Sussexes, “tarnishing their brand”.

Alternatively, Harry could leave court as the “knight in shining armour” – it is all to play for, he said.