The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Plastic, not fantastic: Are reusable food containers really that eco-friendly?

Alejandro Gallego Schmid, Adisa Azapagic and Joan Manuel F Mendoza explore the pros and cons of various food storage options

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We are facing a waste crisis, with landfills across the world at full capacity and mountains of “recycled” waste dumped in developing countries. Food packaging is a major source of this waste, giving rise to an industry of “environmentally friendly” reusable food and drink containers that is projected to be worth £21.3bn worldwide by 2027: well over double its 2019 value of £9.6bn.

But while it might seem like reusing the same container is better than buying a new single-use one each time, our research shows that reusable containers could actually be worse for the environment than their disposable counterparts.

Reusable containers have to be stronger and more durable to withstand being used multiple times – and they have to be cleaned after each use – so they consume more materials and energy, increasing their carbon footprint.

Our research set out to understand how many times you have to reuse a container for it to be the more eco-friendly choice, in the context of the takeaway food industry.

We looked at three of the most widely used types of single-use takeaway containers: aluminium, polypropylene (PP) and extruded polystyrene (commonly known as Styrofoam, but correctly referred to as EPS). We compared these with commonly used reusable polypropylene food containers, popular among eco-conscious consumers.

The results showed clearly that Styrofoam containers are by far the best option for the environment among single-use food containers. This is mainly due to their use of only 7.8g of raw materials compared with PP containers’ 31.8g. Also, they require less electricity for production compared with aluminium containers.

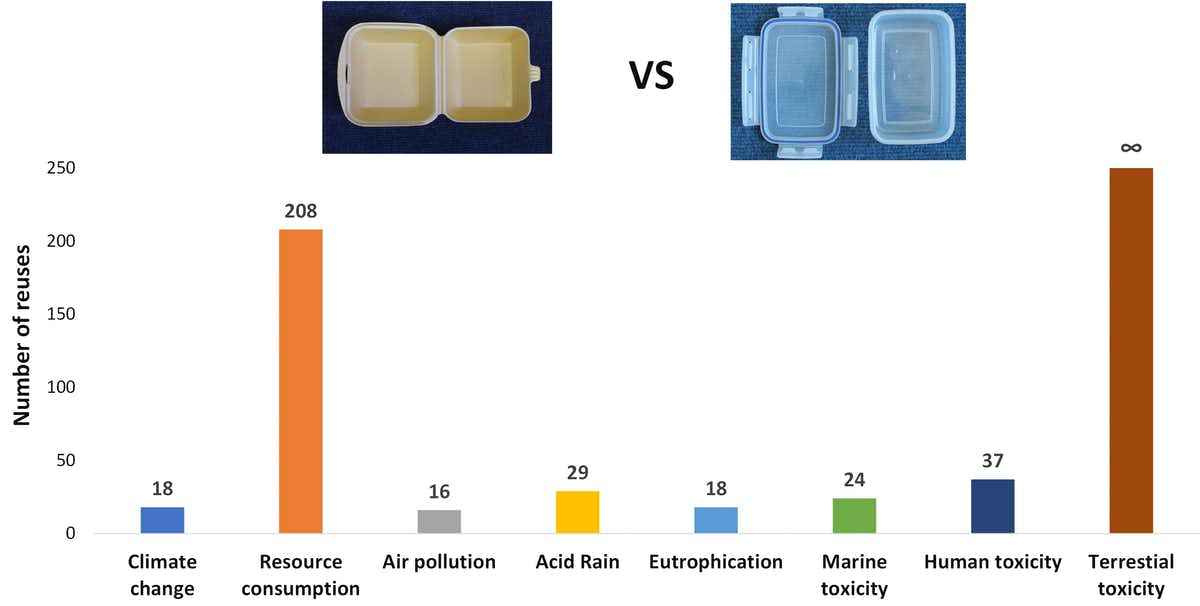

Even a reusable container would have to be reused between 16 and 208 times for its environmental impact to equal that of a single-use Styrofoam container.

We assessed 12 environmental impacts across the entire life cycle of a food container. These included the container’s contribution to global warming and to acid rain, its toxicity to humans and natural ecosystems and its effects on the ozone layer.

Taking these into account, you’d have to reuse a container 16 times to “counteract” the impact on air pollution of using the single-use container – and 208 times to counteract the impact of resource consumption.

When it comes to endangering our landscapes, reusable containers are always a worse option – regardless of the number of times used – due to the electricity required to heat the water for washing them. This is thanks to the emission of substances like heavy metals in electricity generation, which are toxic to many land-based organisms.

Similar results to ours have been reported for coffee cups, with one study concluding that it takes between 20 and 100 uses for a reusable cup to offset its higher greenhouse gas emissions compared to a disposable cup.

Alternatives

A common criticism of Styrofoam containers is that they are not currently recycled. Although technically possible, the low density of Styrofoam (containing 95 per cent air) means that vast amounts need to be collected and compressed before they can be shipped to a recycling plant, making Styrofoam recycling economically tricky.

However, we found that increasing recycling rates for the three types of single-use takeaway containers to the level of the EU’s 2025 packaging waste recycling target (75 per cent for aluminium and 55 per cent for plastic) would reduce their impacts by 2 per cent to 60 per cent. This includes an annual drop in carbon emissions equivalent to taking 55,000 cars off the road.

That doesn’t mean that reusing containers is always worse for the planet. We just need to be realistic about the number of reuses it takes to make environmental sense. But reuse is a considerable challenge for an industry optimised for “on-the-go” consumption.

The takeaway message? Individual packaging will have limited influence as long as the whole system remains in need of a complete overhaul

Unless it is highly convenient or they’re offered an incentive (such as money back), customers aren’t likely to carry around empty containers until they can return or reuse them. There are also potential issues with liability for food poisoning and cross-contamination from allergens when reusing containers.

Despite this, reuse has been shown to work in the takeout sector, as with reusable box schemes like reCIRCLE in Switzerland. However, systems like this require considerable investment, particularly to help customers return containers.

A more promising model may be one where the vendor directly collects empty containers from the customer to be refilled with the same substance, in the style of old-fashioned milk delivery rounds. Similar models, like Terracycle’s Loop, aim to reuse each container up to 100 times.

The bigger picture

Unfortunately, single-use takeaway containers frequently end up contaminating natural environments. Almost half of the plastic polluting the world’s oceans comes from takeaway containers.

But instead of switching from single-use, a better environmental solution may be to encourage food companies to invest in more efficient recycling systems worldwide.

The takeaway message? Individual packaging choices will have limited influence as long as the whole system remains in need of a complete overhaul. For example, a consumer might opt for a compostable container, but that won’t help if their area doesn’t have an industrial composting facility.

It’s time we shifted packaging design from being product-based – focused on providing maximum features and functionality – to user-centred, focusing on improving customers’ lives by empathising with their desires for a cleaner world.

That means coupling environmentally sound and low-impact materials with a waste infrastructure that appreciates how humans actually behave and is designed to help them lead sustainable lives. When convenience and sustainability are pursued together, everyone wins.

Alejandro Gallego Schmid is a senior lecturer in circular economy and life cycle sustainability assessment at the University of Manchester. Adisa Azapagic is a professor of environmental chemical engineering at the University of Manchester. Joan Manuel F Mendoza is a research fellow in circular economy and industrial sustainability at the Ikerbasque Foundation. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments