Mountain man: the miraculous life of Reinhold Messner, the world’s most controversial climber

He was the brash, brilliant and ego-fuelled climber who first scaled Everest without oxygen, survived earthquakes and whose brother was swept to his death as the two men attempted a treacherous descent. As a new controversy sees him stripped of two Guinness world records, Natalie Berry relives the extraordinary highs and shattering lows of a mountaineering colossus

Moments after the elation of reaching the summit of Nanga Parbat at sunset alongside his younger brother, Gunther, Reinhold Messner’s descent into despair began.

At 8,126 metres, on top of the majestic Rupal Face in Pakistan, with no supplemental oxygen, 24-year-old Gunther hallucinated in the thin air, unable to move in the dark. A bitter-cold overnight bivouac near the summit caused his condition to deteriorate, prompting Reinhold to make a judgement: whether or not to attempt to descend via the less steep, but uncharted, Diamir face. Gunther’s torturously slow progress through a maze of precarious ice blocks led to a second endless night.

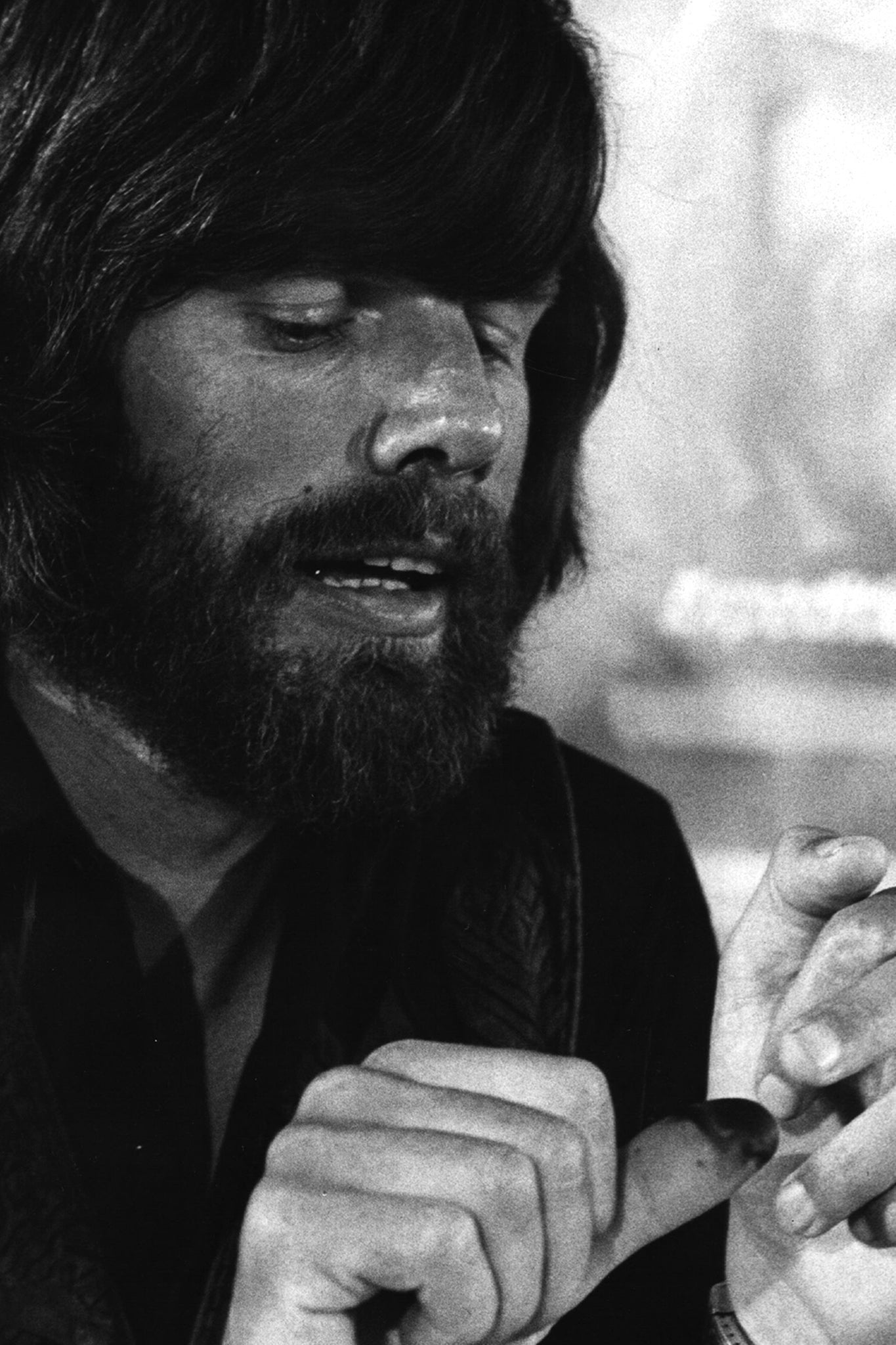

The next day, while Reinhold was picking his way down the glacier, he turned to find that his brother had vanished. Gunther had been seemingly swept away by an avalanche, and buried under snow and ice. Following a desperate, delirious two-day search, Reinhold lost seven toes to frostbite and subsequently faced a separate mountain of accusations, after he was rescued from the glacier himself by local farmers.

Messner’s fellow expedition members rounded on him, saying he’d abandoned Gunther at the summit in order to complete an ambitious traverse of the unclimbed Diamir face without regard to his brother’s safety, leaving Gunther alone to descend the familiar face that they had climbed. Conflicting accounts, lawsuits and a media storm ensued, plunging Messner into a void of depression and despair. The year was 1970.

Many times he returned to Nanga Parbat to try to find Gunther’s body, and with it prove that they had been together below the Diamir face. In 2005, the glacier finally revealed remains – a lower limb in a leather boot, and a headless, decomposed torso – that silenced most, but not all, cynics.

The loss of his younger brother left an indelible mark on Messner. “During the course of this expedition, I died. [...] It wasn’t my body that died, but my spirit, my will, and all my hopes,” he wrote in his book The Big Walls. “I came home alone – and as a different person.”

Last week, Messner found himself at the centre of a fresh controversy. Guinness World Records adjudicators accepted new research from German Eberhard Jurgalski concluding that Messner had come metres short of the “true summit” of Annapurna I in 1985, effectively stripping him of two Guinness records: being the first person to summit all 14 of the 8,000-metre peaks, and the first to do so without bottled oxygen – feats that had helped to define his mountaineering career and status.

The nub of the issue is that the highest point of complex summit ridges can be difficult to determine by eye. While Jurgalski’s team pursued a precise “geographical truth” using modern technology, critics have deemed their work a pedantic “nitpicking” exercise based on a technicality, which could place asterisks beside certain ascents and records in climbing’s history books. The news also sparked a philosophical debate about whether reaching an exact point really matters, and the value of mountaineering records. Messner himself has publicly disputed the evidence, while also claiming not to care about records. The 79-year-old is no stranger to contradictions, having courted scandal and high drama throughout his life.

Born in 1944 in South Tyrol, the autonomous province in the north of Italy which until 1919 was part of Austria, Messner grew up with eight siblings in the Dolomite mountains. His mother Maria was “altruistic” and matriarchal, filling the domestic gaps that his father missed. Josef Messner, a teacher, was a Nazi sympathiser drafted to serve alongside the Germans in Operation Barbarossa on Hitler’s eastern front. Post-war, he was often distant and abusive at home. Messner wrote in a memoir, The Naked Mountain, that he had once found Gunther in a crumpled heap in a dog kennel after their father had lashed him with a whip. But in his lighter moments, Josef introduced his boys to the freedom of the mountains.

Following in the footholds of his father, Messner began an alpine apprenticeship, tackling the towering spires of his native Dolomite rock faces. He later transferred his skills to challenging snow and ice routes in Europe’s Western Alps, using minimal equipment to make fast and efficient ascents. Messner then applied this lightweight “alpine-style” to scaling the eight-thousanders, forgoing supplemental oxygen, fixed ropes, large camps and support teams. He rejected the “siege-style”, nationalistic expeditions that lingered after the Second World War – and also shunned the political views that his father and Austrian-German teammates on Nanga Parbat espoused. Messner was preoccupied with forging a mountaineering philosophy instead, drawing on inspiration from earlier pioneers.

In 1971, he penned a furious essay titled “The Murder of the Impossible”, in which he slammed the modern-day climber for using fixed equipment such as bolts and pegs to lower the challenge and bend the rock face “to his own idea of possibility”. “Who has polluted the pure spring of mountaineering?” he bellowed from the page.

Sometimes Messner’s uncompromising approach proved too much. When he returned to Nanga Parbat – his brother’s icy grave – in 1973 for an “Alpine-style” ascent, he buckled psychologically at 6,500 metres. “I felt so lost and lonely that I turned back,” he wrote in The Naked Mountain. “I wasn’t able to cope with that degree of exposure on my own. I could no longer think clearly. I felt like I was going to pieces.”

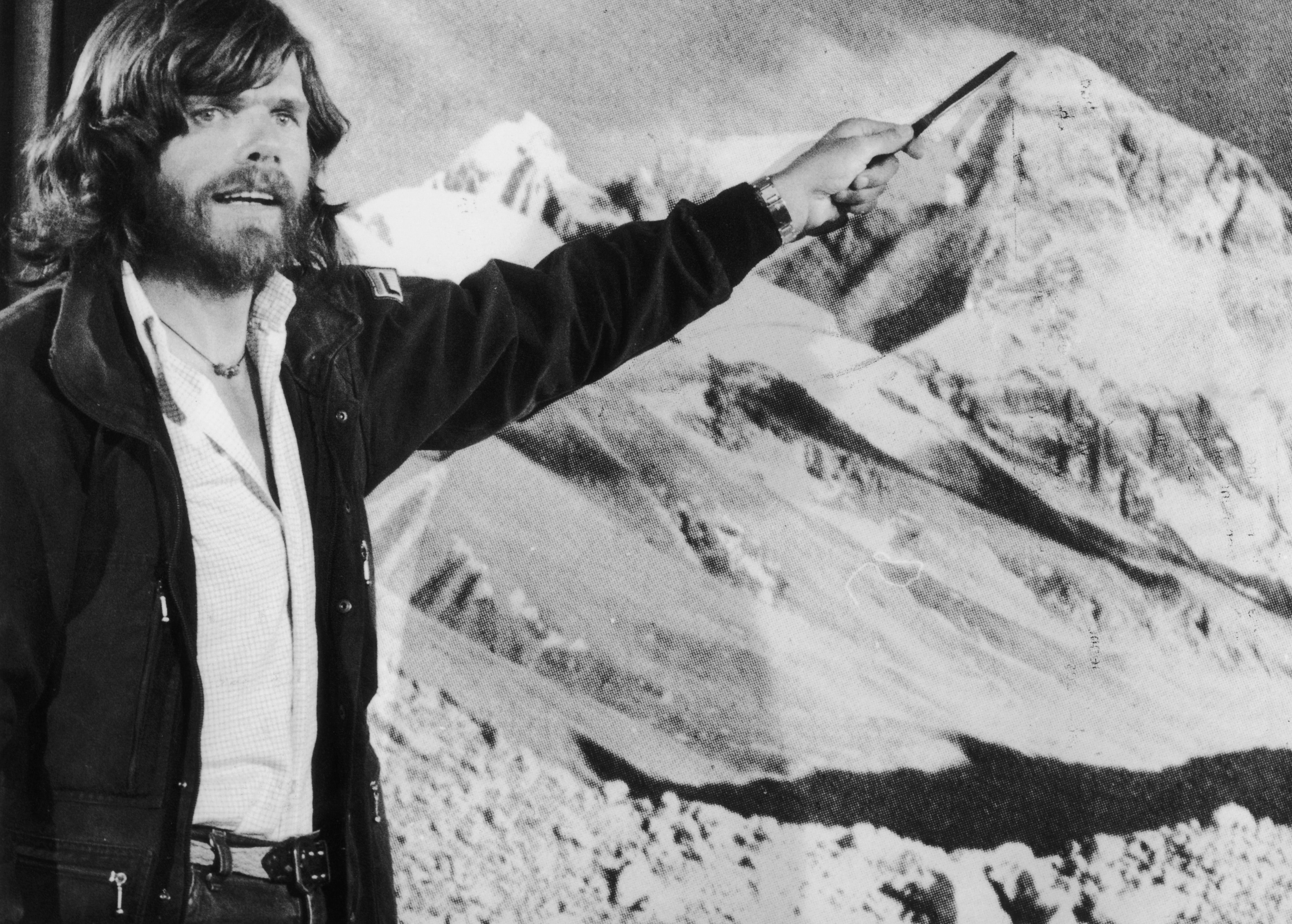

In 1978, Messner defied physicians in achieving the first ascent of Everest without supplemental oxygen, alongside Austrian Peter Habeler. Despite having shared a rope on multiple successful expeditions in the Alps and in South America for over a decade, a dramatic fall-out occurred following Habeler’s publication of a book about the expedition, The Lonely Victory. Habeler accused Messner of overstating his leadership of the climb and of resenting their joint success, accusations that Messner disputed.

Messner’s staunch individualism eventually paid off. That same year, he made the first solo ascent of Nanga Parbat from base camp, via new ascent and descent routes on the Diamir face – the same face that he had painstakingly descended with Gunther, and below which his brother’s body would eventually be found. This was the first solo climb of an 8,000-metre peak. Incredibly, as if this feat were not extraordinary enough, Messner also survived an earthquake during the climb. His route remains unrepeated.

In 1980, his logical progression was to become the first person to solo Mount Everest without bottled oxygen – a feat likened by elite American mountaineer Conrad Anker to “landing on the moon”, to which “everything else kind of pales in comparison”. Messner nearly aborted his attempt after falling into a crevasse and struggling to extricate himself on day one, but resolved to continue, climbing over three days – partially via a new route – during monsoon season.

Yet Messner’s fascinating compulsion for audacious solo climbs was increasingly becoming a symptom of chronic loneliness, likely exacerbated by his first divorce in 1977. He wrote in his book The Crystal Horizon, following his Everest solo: “I am a fool, who with his longing for love and tenderness runs up cold mountains.”

While Messner’s mountaineering predecessors had concerned themselves with reaching virgin summits, he made a career of repeating them via uncharted routes on unclimbed faces, without supplemental oxygen and often solo. In 1986, he became the first to claim the summit of all 14 of the 8,000m peaks, and the first to do so without supplemental oxygen. His last 8,000-metre summit was Lhotse (8,526m).

‘A child doesn’t need a legend’

In 1986, 42-year-old Messner decided that he did not want to climb the highest mountains any more. In the years since, he has turned his hand to myriad and wildly eclectic interests, including cattle-farming, yak-herding, yeti-hunting (unsuccessfully, and writing about it), a five-year stint in politics (as an MEP of the Italian green party), desert-crossings (the Gobi desert, solo), ice-field traverses (Greenland and Antarctica, becoming the first to do so on foot), researching George Mallory’s death on Everest (the subject of another book), and launching six mountain heritage museums across the Dolomites. Now aged 79 and living between two castles in the South Tyrol, Messner keeps active by walking in his local mountains.

Tracing a path reminiscent of his mountaineering feats, Messner’s private life has encompassed many highs and lows. He has been married three times and divorced twice. He had an affair with the wife of one of his Nanga Parbat expedition teammates, eventually marrying and then divorcing her. He has four children, one of whom – Simon Messner, now 33 – became a mountaineer, with first ascents to his name in the Dolomites and on 6,000-metre peaks in Pakistan. Messner was “stiff” and “absent” as a father, Simon claimed in an interview last year with an Italian newspaper.

“I grew up with a father in the spotlight,” he said. “When I wanted to know something about him, I had to read Das Bild. He was always on the move. His head is as hard as marble and he can be very fickle. It was not easy to be the son of a legend. Everyone sees him as a myth, but a child doesn’t need a legend. He needs a father, and [Reinhold] never was.”

Simon emphasised that he had not followed in his father’s footsteps to become a climber; rather, he had decided to climb of his own volition at the age of 17. “I never went climbing with him, nor did he ever take me on his adventures,” he said.

Nonetheless, the pair have together founded the Messner Mountain Movie production company, and in a telling Instagram bio, Simon also describes himself as a “traditional alpinist” – a term coined and oft-quoted by his father.

In 2021, Messner married Sabine Schumacher, from Luxembourg, who is 36 years his junior. Simon disapproved. “I don’t accept that his wife is my sister’s age,” he told the Italian press. “But he is Reinhold: if he has something on his mind, he does it.”

*****

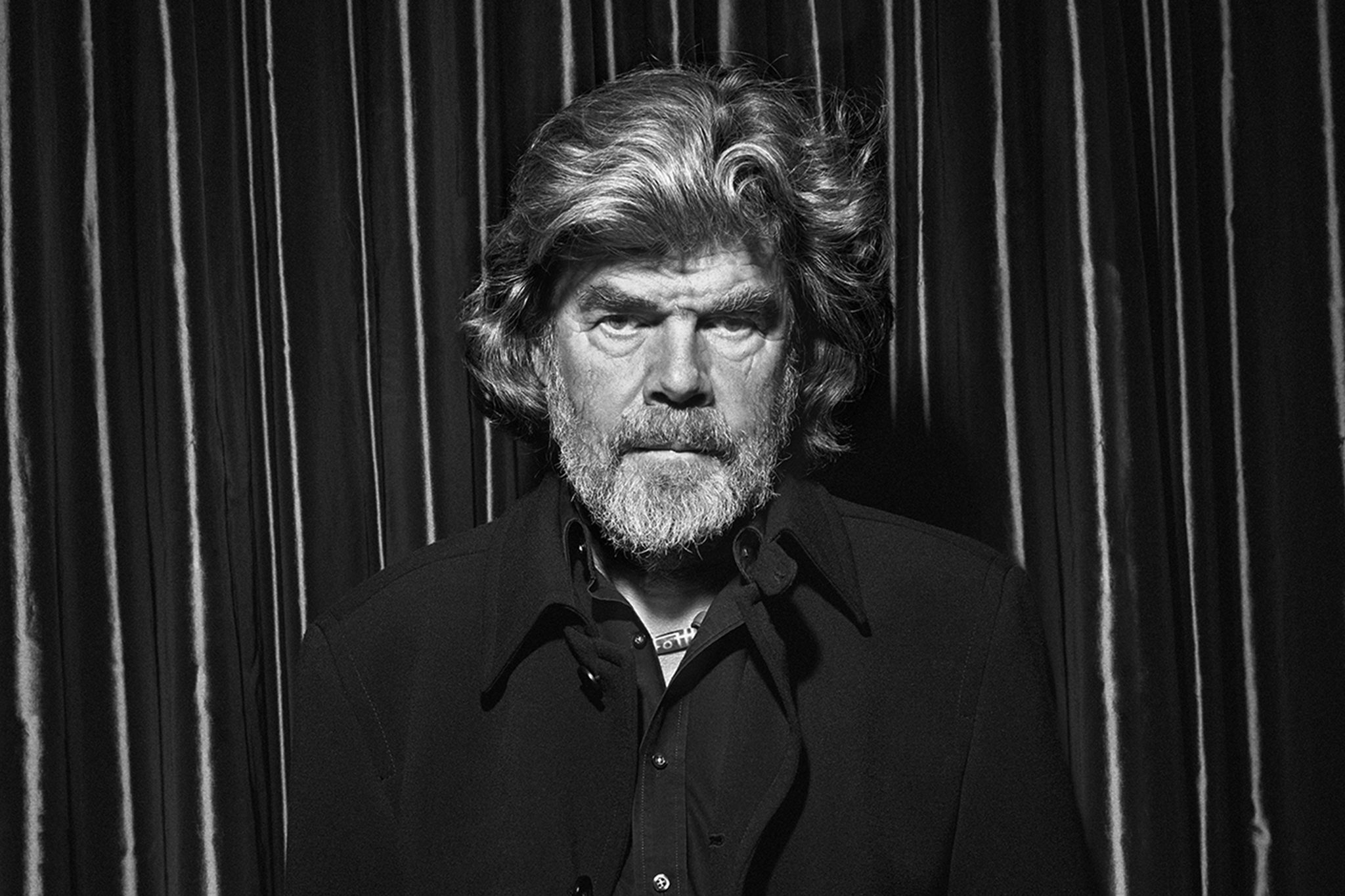

Over the years, journalists, photographers and fans have found Messner to be similarly evasive and stubborn. His brooding appearance – with his furrowed brow, mountaineer’s beard and wild hair – and his irascible persona can be intimidating. “Messner famously doesn’t require oxygen, but I do, and there didn’t seem to be any left in the room,” photographer Jim Herrington wrote of a photoshoot in The Climbers. “Reinhold, you’re scaring all of us,” Herrington quipped. “A smile cracked across his face, there was air to breathe, and finally we could talk... but I still know him no better than I do the remote north face of Everest.”

Messner’s disposition can be as knife-edge as his climbs. He has been described as charming and flamboyant, arrogant and egotistical. An enigma. He has been full of duality. He has criticised large-scale commercial Himalayan expeditions while supporting Himalayan mountain tourism and praising the logistics of 8,000er speed records.

He now claims not to care about summits or records, despite having made a healthy living out of reaching and setting them, respectively – although he usually “drifted into them by accident” as secondary achievements to a summit or style objective, according to Stephen Venables, the first Briton to summit Everest without bottled oxygen.

‘Conqueror of the useless’

There is a tension at the heart of mountaineering between philosophical notions of “the journey” and the record-setting, money-making, ego-stroking obsession with summits.

The latest Guinness World Records “controversy” is either a storm in a teacup or a raging mountain tempest, depending on whom you ask. The question is: does the (redefined) measure of one mountain – a technicality, essentially – make the measure of a mountaineer, or a man?

In 2021, Messner told The New York Times: “If they say, maybe on Annapurna I got five metres below the summit, somewhere on this long ridge, I feel totally OK, I will not even defend myself. If somebody would come and say, ‘This is all bulls***, what you did’? Think what you want.”

In contrast, Messner’s response to the German press last week was defensive, and criticised Jurgalski, who led the research into reinvestigating the true summits of the 8000ers. “He has no idea. He is not an expert. He simply confused the mountain. Of course we reached the summit,” he said. “I’m not interested in whether my name is in the Guinness book. A record that I have never claimed can’t be taken away from me, either.” Messner’s Italian partner on Annapurna I, Hans Kammerlander, called the project “nitpicking by a theorist” in the press.

There’s an irony in Messner, the personification of the uncompromising, purist mountaineer, being told by a “theorist” that it is likely he didn’t reach the top. But the best ascents aren’t measured in metres alone; vision matters, style matters. And the journey, too.

“There will never be any [records] in traditional alpinism! I appreciate every alpinist, every alpinist who makes their experiences on the big walls of this world. That's what it's all about, life. I am and remain the conqueror of the useless but I have gained so much in my life that I can proudly say today I am a happy man!” Messner wrote this week on Instagram. “Not the summit but the path is the goal. My alpinism knows no records!”

This emphasis is different to an earlier perspective he described in My Life at the Limit. “When I am identifying an objective, the summit is everything,” he wrote. “I wouldn’t make it up otherwise. I’m not a superman; I’m just mentally capable of concentrating on the end point.”

But Messner was not solely fixated on summits. “He was an outstandingly gifted and imaginative climber, always interested in exploring new ground – both geographical and psychological – to see what was possible,” Venables says, adding that “mindless” peak-bagging should not be confused with the artistry of Messner’s climbs.

One thing is clear: Messner is infinitely more comfortable in the savage arena of high mountains and rarefied air than he is in the court of public opinion. He appears to hold many conflicting ideas in his head at once, making it difficult to get the measure of the man.

“Great things happen when men and mountains meet,” Messner often says, and once said to The Independent. “That is what William Blake once wrote. It is true. Great things do happen.”

Messner is possibly aware that Blake also experienced the death of a cherished younger brother – who died in 1787, at exactly the same age as Gunther – and was deeply traumatised for life. What is more certain is that this complex man has achieved great things in the mountains, despite losing a brother, some fans, seven toes, and perhaps one “true summit” in the process.

If he fell short on one climb, he went beyond on others – sometimes at great personal cost.

When is a summit not a summit?

Few mountains have a distinct, pointed summit like the iconic Matterhorn. Some, such as Manaslu, Dhaulagiri I or Annapurna I, have undulating summit ridges. The relative altitude of “bumps” can be difficult for climbers to discern – especially in a fatigued, hypoxic state, and in poor visibility. Snow and ice levels also fluctuate, complicating comparisons.

When Messner and early pioneers made their historic ascents, they had access neither to GPS and mapping technology, nor to the internet to verify whether they had reached “the top”.

Jurgalski runs the database 8000ers.com. He’s not a mountaineer, but he is a meticulous chronicler. Using satellite imagery, GPS coordinates, photos, videos and climbers’ descriptions, Jurgalski and his team attempted to determine the “true summit” of each mountain – and who had reached them, or not.

The majority of summiters who were deemed to have failed to reach a “true” summit had done so unknowingly. A minority had deliberately shirked the summit. Some have even returned to complete unfinished business.

What difference does a few metres make?

“This is not about Messner,” says mountaineer Damien Gildea, who investigated alongside Jurgalski. “Our work was about the mountains. I was mainly interested in the ‘true' nature of the summits, and the fact that so many were cheating on Manaslu in the name of convenience and commerce (not Messner). I was focused on the geographical truth, and to examine why this matters, if it does at all.”

A distinction exists between viewing the summit as “the only thing that matters” in the pursuit of peak-bagging records, and considering it a meaningful component of an adventure, says Venables.

Jurgalski concluded that Messner had stopped 65 metres from the true summit of Annapurna I, and five metres below it in elevation. Messner described seeing base camp from his perceived “summit”, but Jurgalski’s calculations suggested that it would not be visible from the true summit. Guinness World Records recognised his research and has since re-awarded both records to Ed Viesturs, an American. “This should in no way detract from the incredible pioneering achievements made by some of the most significant mountaineers over the past 50 years,” Guinness World Records said at the time.

Most climbers would agree that this new knowledge should be applied to summit records in mountaineering-specific history books in future, but not to historical ascents.

Viesturs wrote on Instagram: “I truly believe that Reinhold Messner was the first person to climb all 14 8000ers and should still be recognized as having done so. He led the way, not only in style, but also physically and psychologically, by climbing without supplemental oxygen [...] Climbing mountains is a personal journey, and should not be about being on a list or setting records.”

*Jim Herrington has photographed many of the biggest names in 20th-century climbing. His work can be found here.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments